Reviewed: Michael Lavigne, Not Me (Random House, 2006)

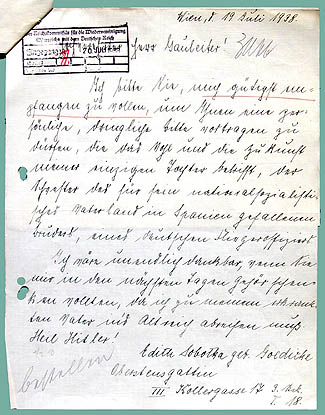

What differentiates the Holocaust from the great human crimes of the years since is less the scale of its carnage but the arch-industrial efficiency of its perpetrators. With bloodbaths like the Cultural Revolution or the Rwandan genocide the slaughterers are frantic or frenzied. There are always suggestions of desperation, chaos, even anarchic collapse. The voluminous SS dossiers and camp log books, the films, the records of medical experiments, and the ledgers of articles stolen from the condemned bespeak something quite different: an insidious confidence and concision that both defies ready explanation and renders the Nazis’ victims all the more abject.

Given the mystery and enormity of the Holocaust, it should not surprise us that artists continue to use it as a historical backdrop for mysteries and moral dramas of their own creation. First time novelist Michael Lavigne’s compelling Not Me is a high-concept mystery that plies the lines between villain and victim, between evil and the pain evil produces. The book is engrossing, even if it does not completely succeed, and even as it may raise questions about the continuing dramatic power of the Holocaust.

Mickey Rose (the stage name of Michael Rosenheim) is a divorced comedian with a less than original sense of humor. His father, Heshel, beset by the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease, lies rapidly declining in a south Florida hospital. Heshel is, as far as Mickey knows, a Holocaust survivor and ardent Zionist, an honored supporter of all causes Jewish who has photographs of himself with Golda Meir, Elie Wiesel, and Natan Sharansky. “The last person in the world I wanted to know about was my father,” begins Mickey, who has traveled to Florida for his father’s last days. “So when I was presented with twenty-four volumes of journals . . . and was told, ‘These are your father’s, take them,’ I was less than enthusiastic. Especially since it was my father who gave them to me.” From this elegantly depicted moment of compounded alienation begins Mickey Rose’s deconstruction. “With survivors,” Mickey observes, “there is always a before. And it is always some halcyon, half-imagined paradise—painted in the rich and shining colors of youth.” With Heshel, however, there was never any talk of the before. He “never compared it to the after. Never spoke of the during.” Heshel’s reticence distanced him from his son; it is a source of Mickey’s bitterness. The dying man is nearly a blank slate. Now, crippled by Alzheimer’s, he does not know his son, and believes his dead daughter has been visiting. But the old bound journals he passes to Mickey  purport to tell a fantastic story. Their writer claims to be not a survivor of the Holocaust but one Heinrich Mueller, an officer and accountant with the Waffen-SS Budget and Construction Office, whose final job for the Reich involves keeping track of the confiscated personal possessions of Jews interned in the Majdanek Concentration Camp. In the final weeks of the war, Mueller, understanding that allied forces are to liberate the camp, starves himself, then carves numbers into his arm, throws away his uniform, and dons the rags of an inmate. He steals the name of a dead Jew: Heshel Rosenheim.

purport to tell a fantastic story. Their writer claims to be not a survivor of the Holocaust but one Heinrich Mueller, an officer and accountant with the Waffen-SS Budget and Construction Office, whose final job for the Reich involves keeping track of the confiscated personal possessions of Jews interned in the Majdanek Concentration Camp. In the final weeks of the war, Mueller, understanding that allied forces are to liberate the camp, starves himself, then carves numbers into his arm, throws away his uniform, and dons the rags of an inmate. He steals the name of a dead Jew: Heshel Rosenheim.

In short order, Heinrich/Heshel finds himself rescued and transported to a kibbutz in Palestine where, even while hating the Jews and dodging exposure by a fellow survivor who claims to have known the real Heshel, he finds himself fighting for Israel’s independence. As if by accretion, his soul is converted and he embraces the life he has stolen for himself. Hatred gives way to respect and then love.

The journal entries are vivid, and it is a testament to Lavigne’s skill as a story-teller that Mueller’s transformation seems not just plausible but convincing. Mickey recoils from the possibility that the story is true. “Certainly,” he argues to himself, imagining the journals to be the product of some kind of therapeutic exercise, “the writing could imply that he was not the Nazi at all, but his victim.” He imagines the journals might contain a fabrication written to blot out some other, horrible crime, something that his father had done in the camps to survive.

No answers emerge quickly. Heshel suffers conveniently from his dementia. Mickey, struggling not just with his father’s illness but with the finality of his divorce and his increasing estrangement from his own son, suffers from paralysis. He stays in his father’s apartment. The books—and, presumably, the solution to the mystery—lie close at hand but Mickey cannot bear to read to their end. Instead, he plumbs his unhappy childhood and adolescence for confirmation of the truth he now dreads. We learn of his father’s curious facility with languages (in particular German) and of his rapt attention to the Nuremberg trials. We hear that family lore holds, with chilling ambiguity, that Heshel was asked, and declined, to be a witness at the trial of Adolph Eichmann. We learn too of the tragic illness and death of Mickey’s older sister.

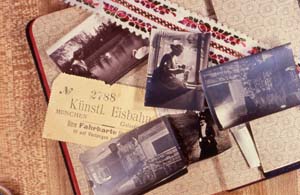

Mickey’s tenuous grip on his own life and his own history threatens to come undone. Looking for clues, he sifts through his parents’ possessions and through the belongings of his sister that they kept. He shifts a couch in his father’s living room, clearing a space as in “one of those war rooms in cop movies, where they tack clues up on the wall.” Up go family photos, birth certificates, an old train ticket, Mickey’s son’s report card, pictures of the liberation of the camps from Life, and post-it notes Mickey has written himself bearing theories that link the ephemera. Meanwhile, there are mysterious signs of other visitors to Heshel. Are they Nazi hunters? Nazis come to reclaim their lost comrade? Mueller’s German family?

Mickey’s tenuous grip on his own life and his own history threatens to come undone. Looking for clues, he sifts through his parents’ possessions and through the belongings of his sister that they kept. He shifts a couch in his father’s living room, clearing a space as in “one of those war rooms in cop movies, where they tack clues up on the wall.” Up go family photos, birth certificates, an old train ticket, Mickey’s son’s report card, pictures of the liberation of the camps from Life, and post-it notes Mickey has written himself bearing theories that link the ephemera. Meanwhile, there are mysterious signs of other visitors to Heshel. Are they Nazi hunters? Nazis come to reclaim their lost comrade? Mueller’s German family?

A slew of obvious moral questions relating to the indelibility of evil and the power of atonement arise from the situation Lavigne has created. And, in a less than subtle bit of staging, much of the novel’s present story takes place during the Days of Awe. To Lavigne’s credit, he does not transform Mickey into a vessel for extended ruminations on the big issues that his father’s journals suggest. Not Me remains focused on Heshel and Mickey, father and son. At his father’s bedside, before reading the final journal, Mickey “caress[es] the flaky, soft leather in [his] hand as if it were an old dog,” and smells “the must rising from its pages as if it were steam rising from [his] mother’s soup.” He may not like his father but he loves the man deeply. In the end, Mickey will accept even horrible truths about the man if those truths bring him closer.

Still, Lavigne’s construction of the basic conceit of Not Me remains less than completely satisfying. First, there are the difficulties that come with a mystery that has at its center a detective who is unwilling (even understandably so) to pursue apparently easily obtainable answers. Readers may find themselves wishing that Mickey would simply sit down and read the balance of the journals. They may find themselves skimming through pages devoted to Mickey, searching out the journal chapters.

Then there is the central problem of the book: Heshel/Heinrich’s moral position and how the reader is to respond to it. In reading Not Me one almost has the sense that Lavigne constructed Heshel/Heinrich so as to excavate the deepest moral hole for the character that might permit at least an argument about the possibility of escape. Mueller is an accountant, not a guard or the operator of an oven. He is an officer but a low ranking one, a venal man and a bigot, but merely a cog in the great apparatus of death, an emblem of the banality of evil. We are to understand that his particular, great crime is the theft of the identity of one of his victims and of victimhood itself. But, of course, he has performed a penance by honorably living what might have become of that man’s life, and now dementia has robbed him of moral agency. As Heshel/Heinrich plots and schemes, we feel little outrage because Lavigne has already made it clear that conversion and, perhaps, redemption lie ahead. As the dying man suffers, we feel a measure of sympathy for him, as we must for the penitent and when the person who is suffering is helpless.

Not Me transcends its set-up in a profoundly strange way. The mystery of Heshel’s identity eclipses almost everything else in the book, including the Holocaust itself. I suspect that thirty or forty years ago this might have made Not Me controversial. That the novel won’t stir any controversy today, that the sentiments the book provokes are not so pronounced, and that Heinrich’s crimes and the suffering he witnesses slip so easily into their assigned places in Lavigne’s apparatus perhaps speak of the diminishment of the dramatic potency of the Holocaust, a possibility that would certainly be remarkable. Some readers may have this possibility in mind as they move through Not Me but it is more likely that they will read as I did, greedily, drawn on by Lavigne’s artful story-telling and the promise of some truth about Heshel/Heinrich at the journals’ end.

I’d have to seek advice from you here. Which is not some thing Which i do! I like reading a post that can make people feel. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!