|

Winner of a Rockower Ribbon. |

Reviewed: Phillip Roth, Everyman Houghton Mifflin, 2006

Once upon a time old school analyst Dr. Spielvogel diagnosed his patient’s problem as a crippling case of displaced morality in an endlessly restless sea of sexual desire. Remember “The Puzzled Penis,” Internationale Zeitschrift fur Psychoanalyse, Vol XXIV? Loyal Rothians know that this seminal article was first cited in Roth’s 1967 novel Portnoy’s Complaint, the ribald masterpiece documenting star patient Alexander Portnoy’s battle with mother, lovers, and that impatient little friend down below:

Portnoy’s Complaint: A disorder in which strongly-felt ethical and altruistic impulses are perpetually warring with extreme sexual longings, often of a perverse nature. Spielvogel says: ‘Acts of exhibitionism, voyeurism, fetishism, auto-eroticism, and oral coitus are plentiful; as a consequence of the patient’s ‘morality,’ however, neither fantasy nor act issues in genuine sexual gratification, but rather in overriding feelings of shame and the dread of retribution, particularly in the form of castration.

It is no surprise that Philip Roth’s newest novel Everymancontinues to dredge through the very same stew of sex and dread – morality and mortality – diagnosed by Dr. Spielvogel. The ever hungry, ever burdened body may be Roth’s most beloved topic and Everymanis a tale of the pleasure, terror, boredom, failure, and wisdom of its fullest, final journey.

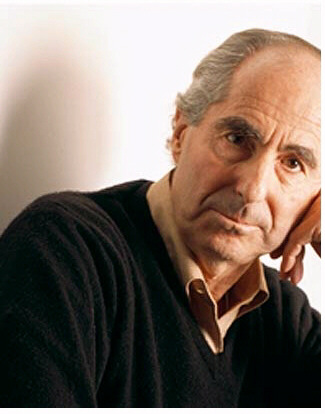

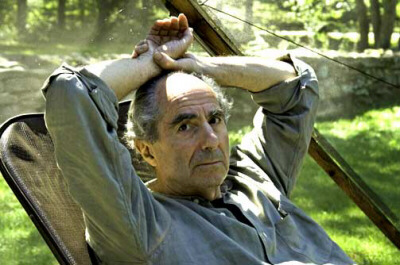

Much time has passed for the rabblerousing author of Portnoy’s Complaint. Roth’s body is now old and his body of work is very, very large. Seventy-three years old following the death of his hero and mentor Saul Bellow in April 2005 – Roth claims to have found the inspiration for writing Everymana day after attending Bellow’s funeral – he is now the dean of Jewish American letters, if not the dean of American Letters as a whole. Roth’s mantel is heavy with literary awards. In the gesture most gratifying for the author, his reputation has been sealed with commitment for publication by 2013 of all of his work in a definitive edition by the Library of America. He has an academic journal devoted wholly to his work. Now an elder statesman, still incredibly prolific, and never one to fear taking on the deepest of philosophical literary callings, Roth uses Everymanto stare unblinkingly through and beyond the human body into the abyss that is its death.

M&M’s

Roth’s novel shares its title with “Everyman,” a dogmatic Christian morality play allegorizing the crux of morality and mortality. An anonymous man in the dotage of an average life with an average overflow of crimes and misdemeanors, the Christian Everyman is not expecting visitors when death knocks on his door. “O Death,” he says, “thou comest when I least had thee in mind…” Everyman asks archetypal friends Fellowship, Discretion, Goods, and many more for comfort and guidance as he is pulled towards death, but none will abide. Only Good Deeds is willing to accompany him out of the world, and through the depth of Good Deeds’ comfort, Everyman repents. Classical Christian lessons of morality are clear: Good deeds coupled with repentance are the best for which human beings, flawed to the core, might strive. Embodying moral life in humility before God mutes death’s blow and brings life’s only purpose and salvation.

In rereading the play’s traditional Christian understanding of morality and mortality through a secular 21st century lens, Roth immerses himself in a thematic pull already familiar in his writing. Morality and mortality have been the heavy twins serving as the axes of some of his greatest work, the shifting poles amongst which Roth’s heroes weave and stumble. See, for example, the troika of 1997-2000’s American Pastoral, I Married A Communist, and The Human Stain, which critic Greil Marcus called “as complete and uncompromised a piece of American art” as any of its era. If the Christian “Everyman” teaches that the soul naturally seeks salvation in the World-to-Come while the flawed, burdening body wishes (at best) to continue to roll in the mud of physical life, the hero of Roth’s Everyman does not think about salvation at all. He lives for life and life only, because in Roth’s world, there are no souls to save. In fact, Roth’s Everyman – nameless while all other main characters (including three ex-wives) have names – claims that if he could write his autobiography it would be entitled The Life and Death of a Male Body. As such, he considers himself a rather ordinary person, or better yet, an “everyman,” an art school graduate who chooses the safe path of a career in advertising, marriage (thrice as mentioned), and children (two unforgiving sons from his first wife and one loving daughter from his second). But what makes Roth’s Everyman most aptly representative of humanity is the merciless, irreversible path he walks towards death without choice or cheer. “Old age isn’t a battle,” he says, “old age is a massacre.” While traditional Christianity offers the opium of the afterlife beyond the visceral world, in Roth’s Everyman, when the body passes, nothing remains.

Despite common narrative frameworks reflecting on the implications of morality and mortality, “Everyman” the play and Everymanthe novel depict antithetical religious worlds. In Roth’s realm religion is a dead end. Yet Roth’s choice of a traditional religious template for his novel suggests more than just an ironic critique of religion. Meditations upon questions of morality and mortality and sex and salvation originating from a religious template suggests an important path for “secular” art – work that admits for itself no religious covenant, empathy, urge, or mission – to engage essential religious questions in modes that most of today’s mainstream writers and thinkers just plain miss. Like most mainstream “secular” writers, Roth cannot ignore religious influence in the formation of his grand questions of art, philosophy, rhetoric, psychology, and literature. And as a writer of grand ideological scope, even if Roth desires to shove traditional answers about ethereal questions aside because of their perceived attachments to religious absurdity, oppression, or boredom, he invariably faces many of the very same challenges engendered by the core philosophical questions within which religious thinking thrives. In Everyman, Roth takes on the role of a modern secular fabulist of religion, crafting a transcendent, iconoclastic, post-religious tale – a morality play for a time when inherited views, practices, and narratives of traditional religions often appear either threatening or obsolete to liberal artists, thinkers, writers, teachers, and readers. As the traditional plot of “Everyman” is laid bare for a provocative secular reading, space opens for new varieties of religious thinking that challenge traditional dogma about essential questions – like what to do about the giant vacancy sign left flashing on lifeless bodies after death. Everymansuggests a creative mode for translating and reimagining religious fetish, teaching, power, and myth about mortality for a post-traditional world.

The Iron Cage

In his last decade of work, Roth has created narratives that unravel American history since the Depression against a backdrop of resurgent Christian fundamentalism in the United States and all variety of fundamentalisms in the lands beyond it. He has critiqued and at times pulverized orthodoxies in spheres political, religious, and social. As a thinker about religious issues and the nature of the soul particularly, Roth takes the staunch anti-religious track of a scientist. More than ever, Everyman brings a scientist’s curiosity, discipline, and vocabulary to the narrative of the body. The book is brimming with juicy medical details – stents and atrial fibrillation and strokes and pain killers and arrhythmias and an army of peers dropping like flies from the killer disease of aging in all of its forms. But neither the hero of the book nor its author is even slightly interested in deliverance for the soul amidst this battle. In fact, in an interview with Jonathan Freeman posted by The Age, Roth said that in doing the research for the book he noted that as people grow older their biography narrows down to their medical biography. They spend time in the care of doctors and hospitals and pharmacies and eventually, as happens here, they become almost identical with their medical biography.

====

Roth notes that the working title for Everymanhad been The Medical History. In Everyman‘s journey, the body in all of its clinical detail – without divine force or intervention to animate it – travels alone. Yet if a body lacks the traditional religious tension of a companion soul charged with navigating its return to the ethereal realm, how, according to Roth, is the body meant to spend its time and define its meaning on earth?

In an interview posted by The Guardian on December 14, 2005, Danish journalist Martin Krasnik asked Philip Roth if he was religious. “I’m exactly the opposite of religious,” he said. “I’m anti-religious. I find religious people hideous. I hate the religious lies. It’s all a big lie.” Then Roth offered the interviewer a question of his own: “Are you  religious yourself?” “No,” said Krasnik, “but I’m sure that life would be easier if I was.” “Oh,” Roth answered, “I don’t think so. I have such a huge dislike. It’s not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion. I don’t even want to talk about it. It’s not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers. When I write, I’m alone. It’s filled with fear and loneliness and anxiety – and I never needed religion to save me.”

religious yourself?” “No,” said Krasnik, “but I’m sure that life would be easier if I was.” “Oh,” Roth answered, “I don’t think so. I have such a huge dislike. It’s not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion. I don’t even want to talk about it. It’s not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers. When I write, I’m alone. It’s filled with fear and loneliness and anxiety – and I never needed religion to save me.”

For the hero of Everyman, a number of options emerge for handling “fear and loneliness and anxiety” after retirement from life as a company man gives his already ubiquitous thoughts of mortality a chance to echo more loudly than ever before. Family offers him one possible direction of making meaning – despite a trail of divorce behind him – most particularly in the form of his beloved daughter Nancy and her twins in New York City. But after 9/11, he moves away from Manhattan out of fear of more terror attacks, settling in a plush retirement community on the Jersey Shore. Once ensconced there, he quickly finds himself bored by opportunities for social succor with fellow old folks and too ambivalent about engaging in the faded draw of sexual pursuits. The hero, always dreaming of life as an artist while perched for a worker’s lifetime at a desk in the office, takes up painting intensely for a period of time. Eventually, even this passion drains and loses its appeal.

The hero of Everyman‘s lack of meaning and “soullessness” is reminiscent of the modern conundrum described by German sociologist Max Weber a century ago. According to Weber, societies founded upon covenants of salvation eventually lose touch with their original charismatic, prophetic impulse. Think of the “National Anthem” recited by children every day at school, “In God We Trust” rustling in your wallet, or Emma Lazarus’ “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” engraved on the Statue of Liberty. For any one paying attention to the recent history of the United States, these salvational anthems and creeds are primarily devoid of meaning in real time. The words and sentiments are hollow, rationalized, and unrelated to the day-to-day life of the vast number of Americans. Devoid of animate meaning, religious roots give way to static social structures and self-serving authority which Weber termed the “iron cage.”

Everyman‘s hero’s deeds are not granted a moral or immoral value as in the case of the Christian allegory. He lives without a personal or communal charismatic, soulful force to guide him through the “fear and loneliness and anxiety” around him. Philip Roth, taking the artist’s path of discovery and meaning, has his devotion to writing to guide him through emptiness, but Roth’s hero goes “from being, entering nowhere without even knowing it.” His death is described as akin to entering the endless, idyllic ocean of the Jersey Shore in which he had frolicked in ecstasy as a boy. Roth’s description of the Great Beyond as the ocean is an absolute contrast to the loneliness and pain of his hero dying without an anchor – despite his marveling at the memories of life’s wonders as he slips away. The ocean represents a cluster of essential religious, mythic symbols: the divine retribution of the Flood, the infinite realm of subconciousness knowledge or wisdom, the cosmic river that girds the universe, the source of all life, or the boundaries of the earth from which humans may not pass. The sea is a mirrored manifestation of the endless possibility of heaven on earth, while life without meaning falls flat with the thud of iron in the mud. Standing over his casket, Everyman’s daughter Nancy quotes her father’s resigned, secular code for living within the “iron cage” of a rationalized, spiritless world:

There’s no remaking reality…Just take it as it comes. Hold your ground and take it as it comes. There’s no other way.

Roth and the Rabbi

The Guardian‘s Krasnik asked Roth to reflect on the Jewishness of his work in their interview as well:

It’s not a question that interests me. I know exactly what it means to be Jewish, and it’s really not interesting. I’m an American. You can’t talk about this without walking straight out into horrible clichés that say nothing about human beings. America is first and foremost … it’s my language. And identity labels have nothing to do with how anyone actually experiences life.

Many make claims for the appropriateness of advocating either for or against Roth’s “Jewish identity.” On the face of it, he is a writer who has devoted much of a sterling literary career to work that is primarily about Jews. Does this not a Jewish writer make? Yet the matter is complicated. A clear trick of Roth’s most recent writing has been to turn nominally Jewish figures – Nathan Zuckerman, Swede Levov, Coleman Silk, and Everyman‘s nameless hero – into distinctly American models for dissecting the crash and burn of particularly American kinds of mortality. The Jew quite literally becomes an American “everyman” in Roth’s milieu. Yet in the area of explicit Jewish content, Roth has also created The Plot Against the Jews, a nightmare of American and world history in which Jewish continuity, always said to hang by a thin thread, is  clipped by the Nazis even in America. Without entering explicitly into the types of political agendas and “horrible clichés” about Roth the Jewish writer that raise his ire, it is useful to think about Philip Roth generally – and specifically in context of Everyman– as a purveyor of contemporary American religious fables containing useful projections into all religious realms, Jewish ones (obviously if not essentially) included.

clipped by the Nazis even in America. Without entering explicitly into the types of political agendas and “horrible clichés” about Roth the Jewish writer that raise his ire, it is useful to think about Philip Roth generally – and specifically in context of Everyman– as a purveyor of contemporary American religious fables containing useful projections into all religious realms, Jewish ones (obviously if not essentially) included.

Artists make us of religious content continually regardless of their respect or antipathy for religion itself because religious content is so rich with ideas and inspiration. It is not necessary to drive Roth the writer or Roth the private person into a Jewish or religious corner in order to understand the contemporary religious use for his iconoclasm. Roth’s vision comes to light when comparing his reworking of the Christian drama “Everyman” with a fable from the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Avodah Zarah 17a, probably recorded in its current form in the 7th or 8th century. The story likely circulated in various forms for centuries in the realms of the Mediterranean and Near East where Judaism, Islam, and Christianity first took shape:

They said of Eleazar ben Durdia that there was not a prostitute in the world with whom he had not had sex at least once.

He heard that there was a prostitute in a town by the sea who took a full purse of dinars as her fee. He took a purse full of dinars and came to her, crossing seven rivers to get there. At the moment of truth she farted. She said, ‘Just like this fart will never return to its place, so too will Eleazar ben Durdia not be received when he turns in repentance.’

He went and sat between two mountains and hills. He said, ‘Mountains and hills, ask for mercy upon me!’ They said, ‘Before we can ask for mercy upon you we must ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, For the mountains shall depart and the hills be removed …’ (Isaiah 54:10). He said, ‘Heavens and earth, ask for mercy upon me!’ They said, ‘Before we can ask for mercy upon you we must ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, For the heavens will disappear like smoke and the earth will wear out like cloth…’ (Isaiah 51:6). He said, ‘Sun and moon, ask for mercy upon me!’ They said, ‘Before we can ask for mercy upon you we must ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, The moon will be humiliated and the sun will be shamed…’ (Isaiah 24:23). He said, ‘Stars and constellations, ask for mercy upon me!’ They said, ‘Before we ask for mercy upon you we have to ask for mercy upon ourselves, as is says, All of the heavenly host will melt…’ (Isaiah 34:4).

He said, ‘It depends on me and me alone.’ He put his head between his knees and shook with weeping until his soul departed. A heavenly voice declared, ‘Rabbi Eleazar ben Durdia is ready for the World-to-Come!’

In both Everymanthe novel and the story of Eleazar ben Durdia a hero battles both moral codes and his own mortality. Wise visitors offer direction urging the hero towards death in each fable. In the talmudic story, natural forces personified as rabbinic teachers quote biblical verses, citing their obedience and even lack of choice before God. Their role is to turn Eleazar ben Durdia towards himself so that he might recognize that only he can save himself through body-emptying weeping, a well known mystical practice which seems not only to demonstrate his worthiness for the next world, but essentially melts and merges his physical body into the matterless world beyond. Roth’s Everyman, in the moments before departure from the world and perhaps as a literary nod to the Good Deeds (but not repentance!) of the play, says, “[H]e had only to yearn for them to conjure them up.” These are the figures of the family love of his boyhood, carriers of the innocent moments of his past that are the closest thing to Good Deeds he can find.

====

Links between the irresistible drive for sex in both Everymanand the story of Eleazar ben Durdia are obvious. Roth’s characters have slept their way around the world just like their rabbinic forbearer. Eleazar’s promiscuity crashes him up against his own potential to be redeemed. The hero of Everyman, perhaps in a tamer way than many of Roth’s earlier protagonists, crashes up against social propriety, but seeks no redemption and asks for no purification at the end of his life. While Eleazar ben Durdia resolves the conflict of morality and mortality with the weeping of repentance accepted by the divine realm, Roth’s Everyman comes to his final shore with pain and loneliness, even as he is girded by an almost nihilistic, personal code. He is resigned and unrepentant.

All is Hot Air

King Solomon – traditionally credited with writing The Book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet in Hebrew), Proverbs (Sefer Mishlei), and the Song of Songs (Shir HaShirim) – shares a costly fascination with women with Roth’s hero and Eleazar ben Durdia. It is said that Solomon – whose father David killed Uriah for the love of the bathing beauty Bat-Sheva, Solomon’s mother – had one thousand wives, consorts, and concubines. A typically complex biblical figure, his desire and hubris lead not only to habitual womanizing, but also to the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem, arguably the pinnacle institutional religious accomplishment of the Hebrew Bible. It is also taught that the elderly Solomon wrote The Book of Ecclesiastesafter a lifetime of battles won and lost in fields both personal and public. At times bitter, but mostly grounded in stoic resignation on the meaning of morality and mortality, The Book of Ecclesiastes contains the famous verses “To everything there is a season and a time for every purpose under heaven…” However, the most interesting textual parallel between The Book of Ecclesiastes, Everyman, and Eleazar den Durdia is the first line of the biblical text:

King Solomon – traditionally credited with writing The Book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet in Hebrew), Proverbs (Sefer Mishlei), and the Song of Songs (Shir HaShirim) – shares a costly fascination with women with Roth’s hero and Eleazar ben Durdia. It is said that Solomon – whose father David killed Uriah for the love of the bathing beauty Bat-Sheva, Solomon’s mother – had one thousand wives, consorts, and concubines. A typically complex biblical figure, his desire and hubris lead not only to habitual womanizing, but also to the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem, arguably the pinnacle institutional religious accomplishment of the Hebrew Bible. It is also taught that the elderly Solomon wrote The Book of Ecclesiastesafter a lifetime of battles won and lost in fields both personal and public. At times bitter, but mostly grounded in stoic resignation on the meaning of morality and mortality, The Book of Ecclesiastes contains the famous verses “To everything there is a season and a time for every purpose under heaven…” However, the most interesting textual parallel between The Book of Ecclesiastes, Everyman, and Eleazar den Durdia is the first line of the biblical text:

The words of Kohelet [Solomon], son of David, king in Jerusalem: Vanity of vanities, says Kohelet, vanity of vanities: All is vanity.

The classical English translation of this verse does not carry the richness of the original Hebrew, Hevel hevelim,. The word “hevel, ” can also be translated as “folly.” Namely, life is a “folly of follies” – all is meaningless, all a waste of time. An even tighter reading suggests translation of “hevel” as the Hebrew term denoting “breath,” or, even closer, “hot air.” Life is ether. Life is gas. Life consists of molecules floating without aim in the endless spheres of the endless universe and everything passes in the end…or through the end. This same sentiment can be found in the colloquial terms of the prostitute in the Eleazar den Durdia story: “Without redemption, life is like a fart. It is a gas. It passes…And it stinks.” Roth’s Everyman knows this truism well. The affair that destroys his one seemingly stable marriage is driven by his inability to keep away from the “little hole” of a Danish model. He literally cannot stay away from entering her behind and this turns his life to crap.

Solomon works his way towards resolution of the seeming meaninglessness of life at the close of The Book of Ecclesiastes, stating that, despite all doubts and conflicts, one must “fear God” and live a life of doing God’s will through proper practice. There is some controversy about the general intent of this sentiment in the text. Both contemporary and traditional scholars suggest that an ideological code in line with more “mainstream” views is presented by the author or later editors in order to make an otherwise challenging, iconoclastic moral code more palatable. But The Book of Ecclesiastesis an example of “wisdom literature,” and much like The Book of Job it is a mixture of philosophy, challenge, submission and sheer dilemma upon which the reader must meditate. The strong urge within the text for stoic resignation in the face of the constant ebb and flow of life – fortune and penury, joy and despair, love and loneliness, ecstasy and fear – is not any less vibrant because of conflicting statements about other kinds of faith. As a whole, the text exhorts courage for living amidst worldly paradox, just as much later Jewish poet Bob Dylan would sing in “I Am a Lonesome Hobo” (1968):

Kind ladies and kind gentlemen, Soon I will be gone, But let me just warn you all, Before I do pass on; Stay free from petty jealousies, Live by no man’s code, And hold your judgment for yourself Lest you end up on this road.

Solomon warns, the prostitute reminds, and Eleazar understands: life is transparent, absurd, unpredictable, and as the Poet says, blowin’ in the wind.

Roth as a Marginal Prophet

Philip Roth does not need to be a rabbi or a priest or to be even remotely connected with religious practice or belief in order to write a religiously meaningful fable for times that demand much resignation and courage from those – religious and secular – who stand against religious hypocrisy and the rationalization of the religious impulse. Max Weber once wrote:

No one knows who will live in this [iron] cage in the future, or whether at the end of this tremendous development entirely new prophets will arise, or there will be a great rebirth of old ideas and ideals.

Could it be that Philip Roth is one of these “marginal prophets” challenging the ghosts of religion and stalking the iron cage? Sigmund Freud – the figure who inspired Roth’s Dr. Spielvogel and a rich source of both parody and insight for Roth and his contemporaries – shares Roth’s ideological rootedness in sexual conflicts as well as a rationalistic disbelief in soul and salvation. The two also share an interesting overlap in the symbolic use of the ocean as a metaphor for the limits of life imbalanced towards scientific, rational tendencies – the tendency which Freud’s contemporary Weber warned against. Beginning in 1923, Freud corresponded with Romain Rolland, a French novelist challenging that Freud’s writings on religion had quite missed capturing the essence of the religious ethos. Rolland claimed that a proper theory of religiosity must describe the essential “oceanic feeling” of emotional and spiritual connectedness within which a person of religious temperament experiences life. Writing with admiration if not full recognition for Rolland’s challenge in Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud reveals much about himself and his intellectual path: “I cannot discover this oceanic feeling in myself. It is not easy to deal scientifically with feelings.” While Freud and Roth share a scientific fascination with unraveling the inner motivations of people, Roth, as an artist, releases his imagination not only to the investigation of morality and mortality, but also pursues a fully engaged, empathic description of the experience of the “oceanic feelings” for his characters. Despite claims to be “anti-religious,”, Roth’s work is thick with religious meaning. In a fable of contemporary death and dying, his hero ends his earthly days with a plunge into primal, cleansing waters. This is the place, at the end of a retelling of an ancient religious motif, where the bars of rationality break open and the reader is asked to pause for a long, deep breath. Here, a person just like the reader has watched his life pass before his eyes. The reader is asked to meditate without preconceptions beyond the body, where new, iconoclastic, redemptive questions of meaning can begin. In engaging the very same raw, ineluctably religious material as countless sages, demogogues, prophets, poets, and kings, a contemporary secularist driven to strip away religious hypocrisy stares down a world hobbled by religious violence, divisions, and lies. The symptomatic shadows of tradition fall away as the dogmatic burdens of morality and mortality dissolve. A marginal prophet guides the reader’s heart towards “oceanic feeling” though the lonely, finite journey of a fictional hero – and that is why this book is called Everyman.

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this post is amazing, great written and include approximately all significant infos. I would like to see extra posts like this.

Hello! I just would want to give you a enormous thumbs up for the fantastic info you’ve got here with this post. I’ll be returning to your blog site for additional soon.