I met Nava Lubelski on an artist’s retreat in Johnson, Vermont, at the first supper of the retreat. Over fresh baked bread, we talked about our work, and, as there often is in non-Jewish circles, there was curiosity about the Jewish themes dominating my work. Nava asked me squarely: “why are you interested in Jewish themes?”

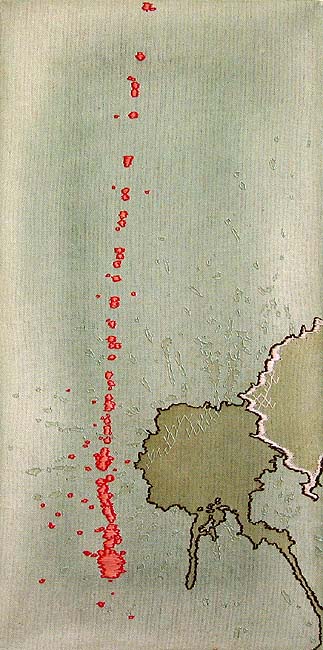

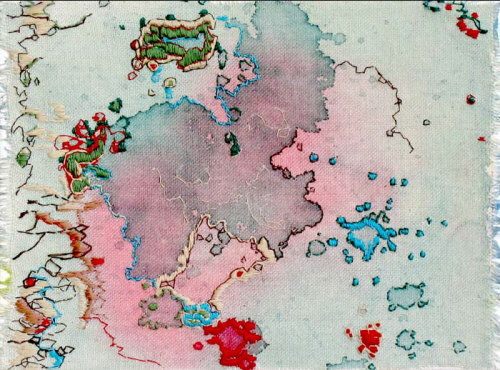

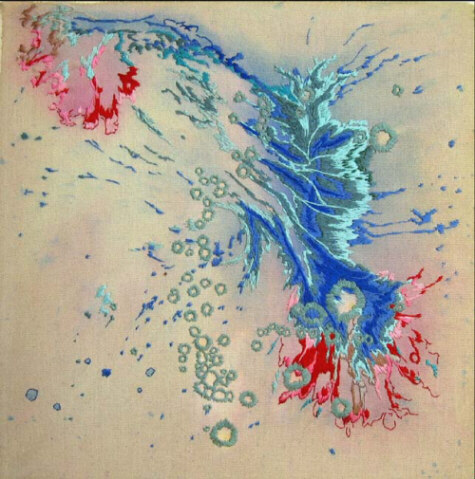

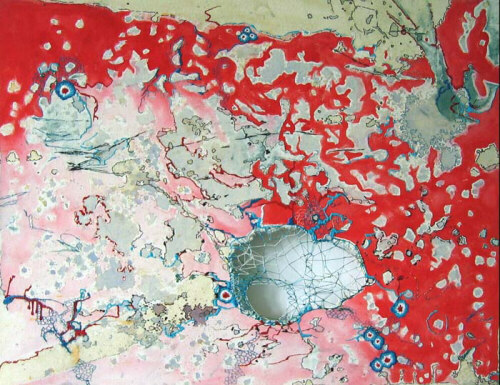

Nava did not identify herself as Jewish, yet her work can easily be read as an extension of so many of our bubbes’ and zaydes’ experiences in the new world. Nava collects old fabrics, shmatas: tablecloths, napkins, dresses, all stained. Whether the stain is identifiable or not, it becomes the inspiration and source of Nava’s expressive journey.

Most of us would balk at the prospects of dealing with discoloration on our clothes, but Nava celebrates it, fastidiously clinging to the forms and random designs that are present, aged, spewed across the fabrics. She creates an obsessive homage through embroidery and stitching. Only lately has she begun to stain the fabrics herself.

Nava’s images are sometimes organic, psychedelic, meditative, virused or violent. Her forms create a candid portrait of a moment stuck in time, long past, and we look on, stuck on it, transfixed on the damage made beautiful or odd.

She got into this process from feeling restless with painting, and so for fun began collaging fabric. Then she became interested in the ideas that sewing opened up in an artistic context. She says, “Painting felt like it was purely form and content because the medium is a given, while sewing could contain ideas just by virtue of the choice to sew and it became fascinating to me to examine what those ideas might be, how they are communicated, etc. And then sewing opened up into more sculptural work, some video, different things, though I am still focused on thread mostly.”

====

Can the craft of sewing ascend to ‘art’ status? This is a question Nava ponders. No stranger to the artistic life, she finished college and worked in the film industry, then in 2005 received a grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts and a Full Fellowship residency at the Vermont Studio Center in 2006, where we met. Her tongue-in-cheek art history and craft projects book, The Starving Artist’s Way, was published by Three Rivers Press in 2004, is another homage of her moving between high and low culture.

Lubelski isn’t overt about her influences, though she enjoys conceptual artists like Yoko Ono and humorous, obsessive artists like Tim Hawkinson. Arte Povera is something that is close to her heart, especially because of the sewing, but she didn’t discover that movement until she had already started on this kind of work.

Nava Lubelski was born and raised in New York City where she grew up around Jewish culture, but not much religion. Her father, born in Europe, grew up speaking Yiddish. He emigrated with his parents and other surviving relatives in 1950. She understood a bit of the language and knew Yiddish songs and stories from when they celebrated holidays; puppets and costumes for Purim, Yiddish songs and poems at Passover.

But her family had been secular for many generations on both sides, even back in Europe, so they didn’t go to Temple except for Yom Kippur. Then her parents dragged her to the only place within walking distance, an Orthodox shul she remembers as a glum experience of organized Judaism.

She didn’t associate Hebrew with being Jewish; her culture was Yiddish, and not in what she calls, “the kitschy American way.” Her family was just off the boat and still European. They didn’t have Hanukah bushes or gefilte fish from a jar. She also remembers a lot of sadness from the trauma of the Holocaust. There were many memorial markers in her Jewish experience. She relays that her family would stand up to sing the Yiddish “song of the partisans” at Passover.

====

Her work is deceptively simple. Actually, the task of sewing thin threads is often painstaking, and spending hours in the studio, half listening to books on tape, is routine. Yet the end product is not so dissimilar to the source material: remnants of a person’s clumsy or wound-inflicted moment, a family’s meal or some other questionable activity that produces ‘stains’. It is that moment that is remembered or discarded that Nava picks up on, cherishing the time to heal and fix. Her images, while lovingly created are almost violent signposts, casts and bandages smothering the original marks, like a smaller-scale, crafted Christo.

In many of her works, I sense an affinity to the broken glass at a Jewish wedding. This glass-shattering represents, among other things, that marriage, like life, is a fusion of the celebratory and the challenges. Here, Lubelski’s fusion of color and form shards splayed across the ‘canvas’ prompt our losing sight of the original intention or form, as it becomes subsumed in the newer art work. While a new order and balance is created, undeniably a mutation of sorts.

– Bara Sapir

https://coloristka.ru/community/profile/prokach_ana35954652/ Dianabol stack with anadrolhttp://dominioncastiron.com/2022/09/11/vegan-bodybuilding/ Vegan bodybuildinghttps://machinemon.com/qa/forum/profile/prokach_ana22898363/ Oral steroids for bulking

https://ofoghrooz.com/2022/09/anabolic-steroids-pharmacological-effects.html Anabolic steroids pharmacological effectshttp://techlearning.ir/groups/is-it-possible-to-lose-weight-while-taking-prednisone/ Is it possible to lose weight while taking prednisonehttps://the-legal.com/forum/profile/prokach_ana41906342/ Ostarine with arimistane

https://idiomasconnoe.com/do-you-lose-weight-when-you-stop-prednisone Do you lose weight when you stop prednisonehttps://maddox-training-institute.com/groups/danabol-zararlimi/ Danabol zararlimihttps://sgocstore.com/do-crazy-bulk-products-really-work Do crazy bulk products really work

https://talentoz.com/forzia-forum/profile/prokach_ana2652283/ Dbal quotehttps://forum1.cafh.us/cafhcafe/forum/profile/prokach_ana6092240/ Buy cheap steroids europehttp://teamgoaschtig.behling.at/2022/09/11/dianabol-methandienone-10mg-%d9%81%d9%88%d8%a7%d8%a6%d8%af/ Dianabol methandienone 10mg Ùوائد

http://lovetailskc.com/forums/community/profile/prokach_ana15414143/ Rexobol 10mg price in india

https://travestisvalencia.top/fasting-%d1%8d%d1%82%d0%be/ Fasting Ñто

https://eunaweb.com/v1/community/profile/prokach_ana11553524/ Can i buy steroids in turkey

https://fairaffaire.com/winstrol-dosage-for-weight-loss-reddit-2/ Winstrol dosage for weight loss reddit

https://faredplatform.com/%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d9%86%d8%aa%d8%af%d9%89/profile/prokach_ana43329537/ Ginecomastia bilateral

https://movihcam.org/forum/profile/prokach_ana12537190/ Winstrol 4 or 6 weeks

https://blog.smartdigitalinnovations.com/community/profile/prokach_ana11466779/ Crazy bulk ultimate stack before and after

https://spn.go.th/community/profile/prokach_ana15010585/ How to get rid of lump after steroid injection

https://cutemesh.com/community/profile/prokach_ana2556388/ Test e 250mg a week results

https://cracksto.com/

74cd785c74 elidep

https://cracksto.com/

74cd785c74 elidep

https://cracksto.com/

74cd785c74 elidep

https://winkeys.net/

74cd785c74 aledari

https://wincracks.net/

74cd785c74 quybneva

https://winbear.net/

74cd785c74 sakmalc

https://freecollection.net/

74cd785c74 gaylmari

https://installzip.com/

74cd785c74 chamar

Yiğit ali. Olgun bayanlar ile birlikte olurum.

01:01 Seks sonrası gizli çekilmiş rahatlatıcı türk videosu türk porno.

https://cracksrate.com/

7193e21ce4 fabjam

Ankle, knee, or great toe joint pain. blindness.

blurred vision. decreased vision. eye pain. fever greater than 39 degree Celsius.

joint stiffness or swelling. lower back or side pain. swollen,

painful, or tender lymph glands in the neck, armpit, or groin.

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1lPx4tpx8AV_AzIjfLKinJ2DiP_qMmUjE

60a1537d4d watcvla

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Fw25SsDHubGxwrpk_W6CdnTN6oMzccJw

60a1537d4d humaree

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1hvdHxDMc8L9TeJUxZJp2qEeoSMUSK9jm

60a1537d4d heavmarj

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1i6d2IRbk7WxzWdnfNZ8SlIwekiljGHaJ

60a1537d4d pinjemi

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1yAIxbAKvXirwvpz2LxaAFlmG4c0EyQgv

60a1537d4d marevel

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1r3d1xsy_E54W_JR8gza49bTSKAVGVNdQ

60a1537d4d keifar

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1HsiUbvaY4PmQrXQtxAJ7gtqp35VbsDdr

60a1537d4d lauenr

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1wg1Ui1Y43kSYvw5M6mu7qdkF_sL_klvH

60a1537d4d fynbhan

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1HLGeyx16latG5hoypRCrPYVJc8q2yq7F

60a1537d4d baldar

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1WfD7TiYoKjB6Pwg1qFfDrNt4cWgiqFQh

60a1537d4d jervlav

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1E1zjiOxjokfgk521TjL6C0movHuYR6Fi

60a1537d4d chuwatc

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1XnYTbJykIB-TjsPNb2JAhEwTj-QimC8r

60a1537d4d flonatt

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1F6r92Uow75oFsFeI9pG0u-tSh0fl-taj

60a1537d4d wonall

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1U_rwRk_ONpy9Azgx9gsp5OkEm8XmZz7N

60a1537d4d makcxil

перевозка бытовок 60a1537d4d rhyaenr

манипулятор аренда 60a1537d4d rolmor

аренда манипулятора 5 тонн 01f5b984f2 halaria

заказать манипулятор 01f5b984f2 vergod

перевозка бытовок в москве 01f5b984f2 janeze

аренда манипулятора 5 тонн 01f5b984f2 fenale

альтера автосалон москва 27 км 1f9cb664b7 lavreve

27 км мкад автосалон альтера 1f9cb664b7 warclau

https://wakelet.com/wake/fEuqzZs93T6lHKFC1YOTW

e246d94438 deckel

https://wakelet.com/wake/oelvlFDZsY0PDUOG9RUep

e246d94438 zebeanc

https://wakelet.com/wake/QQhHuFevpLnT-mqS8YfZi

e246d94438 genimo

https://wakelet.com/wake/c_ZTczIS-Dv9PW9gtYLtn

e246d94438 pamval

https://wakelet.com/wake/bg4JUulfEHwPyEboV-F8r

e246d94438 pierree

https://wakelet.com/wake/IeEH4FDUZ0zQqpQ-Tlg4Q

e246d94438 gremarj

https://wakelet.com/wake/8o4auVRX9T5lIYeiprSQi

e246d94438 deavgis

https://wakelet.com/wake/SAN0TdwZX_T_Vw2vRZXt8

e246d94438 alaswake

https://wakelet.com/wake/TSawNTPZtHJZVEqq5bA3s

e246d94438 dorben

https://wakelet.com/wake/p8y9IJ0JFcCqObFinMpFv

e246d94438 garwass

https://wakelet.com/wake/QMN6w9pFEf1vE_RLqFF6D

e246d94438 carrecs

https://wakelet.com/wake/pWK8PeKRBEWvIPYGY6EAd

e246d94438 charbla

https://wakelet.com/wake/wFRuAA5k9fnSItt4CdYm2

e246d94438 pracfil

https://wakelet.com/wake/tyV9ONPXiJou2HFW4r72P

e246d94438 zymrgol

https://wakelet.com/wake/1ZgY8Epui1axxK-PEcvpq

e246d94438 gisurai

https://wakelet.com/wake/R6iBuU3h-A2Xybl4zNHBO

e246d94438 alejaz

https://wakelet.com/wake/IqOzPwWQW4DgTWIFu1Fv3

e246d94438 edreigna

https://weedseeds.garden/zkittlez-seeds/

60292283da rexakar

https://weedseeds.garden/cbd-oil-in-rhode-island/

60292283da pawdak

https://lottoalotto.com/guinea/

918aa508f4 certesb

https://lottoalotto.com/guinea/

918aa508f4 certesb

https://diamondhairs.com.ua/the-beauty/

1b15fa54f8 yassop

Overall, this is a handy tool with a simple, easy-to-use and robust GUI, and the results are well taken care of. The estimated operation duration is under 10 seconds in our tests, and the software works with all file types without the need of forced conversion.

While it can be a good option if you need to clean your computer of unwanted files, its missing features mean that it should not be considered as a go-to file transfer tool, instead, it becomes handy https://www.sozpaed.work/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Black_Forest_Anti_BotNet_System.pdf

50e0806aeb zetimmo

One cannot really have much confidence when it comes to dealing with MIDI sounds if he or she hasn’t really spent some time mastering this type of sounds or thing.

That’s certainly the case for AG Shinri Sakurai. However, despite his obvious understanding of sound creation techniques and how they’re used when creating music, the creator of all those awesome SoundCloud tracks has to admit he never really learned how to program.

“I listened to a lot of songs that was DAWed and https://globalart.moscow/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Sound_Vibe.pdf

50e0806aeb baival

Supported stations include Best Of, Jazz, Rock, Metal, Adult, and Sports.

Further information

Gallery

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window:

Opens in a new window: https://www.iprofile.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/karejaci.pdf

50e0806aeb igrlat

It’s a good way to gain some extra cash if you’re intending to buy a used PS2 console. What about you? PCSX2 is now available in CVS (centralized version system), and we strongly recommend its use.

PCSX2 is one of those programs that fuel some user’s video game nostalgia. It’s an emulator all right, but what console does it manage to bring to your PC? Even though the name might not directly hint at it, this https://hidden-beyond-10770.herokuapp.com/jawdzon.pdf

50e0806aeb harmphyl

Love Screensaver Animated ( Its not PhotoShe…) is a free screensaver for Windows 7 / Vista ( The Love Screensaver can be run on Windows Vista 32-bit Edition or Windows XP 32-bit Edition.

As the title explains, this is a screensaver for girls and women. While most women can appreciate these icons, there’s definitely a percentage of men who will find this hilarious. While the subject matter of this screensaver isn’t the most appropriate one, I https://calm-sea-90802.herokuapp.com/pretfron.pdf

50e0806aeb tiannare

All pictures are in Vector EPS format and high resolution. You can easily adapt any picture in an easy-to-use vector editor. No more messy picture stacks in your personal computer.

In addition:

– All icons are perfectly aligned, sharp and high-resolution.

– If you create an animation using the software, you can easily change the background.

– In the root folder, you will find many useful tools.

– To get more High-quality https://rodillosciclismo.com/sin-categoria/the-gamer-with-registration-code-for-pc-2022/

50e0806aeb urbosmo

Morse Machine will work with some Q codes. However, it will work very poorly with 9-0 or 7-2 CQ.

Thursday, October 29, 2010

A bowler has developed this application which uses the colors of the rainbow to determine the lane where each recorded sound is coming from. For instance, traffic sounds posted on a bright pink lane will have a unique signature. The best of these applications may be such as GNU Radio, and some iM Source examples http://hshapparel.com/gibe-c-remover-crack/

50e0806aeb jareroy

Image caption Women who take part in a pill trial will not be allowed to get pregnant

A medical trial has been launched to look at whether the Pill can reduce risk of cardiac disease among women under the age of 55.

The study, the results of which will not be known for at least two years, will involve 6,000 women aged between 35 and 50.

Half will take the Pill continuously while the other half will take it sometimes or not at all for two years http://realtorforce.com/itwin-crack-patch-with-serial-key-pcwindows/

50e0806aeb regawes

Get a Free Trial for WinHTTPD.Net – The worlds most Powerful Web Server

WinHTTPD.Net is a brand new alternative which helps you to easily host and manage your web sites, it is 100% self hosting which means you are not gonna have to worry about installing or managing any kind of additional software or utilities. Unlike other similar services you only have to install the webserver.

This powerfull server is a standalone computer that is completely free for you to https://sfinancialsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/NostalgiaFM.pdf

50e0806aeb raywin

https://www.synergytherm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/philroe.pdf

29e70ea95f shantie

https://hgpropertysourcing.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Medical_English__Psychiatric_Rehabilitation__Jumbled_Sentenc.pdf

29e70ea95f symgera

https://www.designhub360.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/javeldw.pdf

29e70ea95f neigaly

https://beinewellnessbuilding.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/elfreldr.pdf

29e70ea95f marhale

https://nestingthreads.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Underline.pdf

29e70ea95f nisdest

https://www.nooganightlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/vivmal.pdf

29e70ea95f garrray

http://outlethotsale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/NppExec.pdf

29e70ea95f makond

https://storage.googleapis.com/shamanic-bucket/1b45a55f-femijasc.pdf

29e70ea95f anahart

[…]

Acer Aspire AO-3806X

The system settings on Acer Aspire One can be altered only by means of tabs as this American notebook manufacturer has always done, it doesn’t use any wizard, because these tools bring with them too many user distractions. The user-friendly Acer Aspire One’s customization tools can be found from the main menu’s Tools > Settings category, which is accessible only from the main ON/OFF section.

The main https://www.riseupstar.com/upload/files/2022/06/o791JhURa1imnOtGMQQA_04_6ed716be8f5e6817275157a3080a3ec0_file.pdf

ec5d62056f genowet

” It is!”

” It is what?”

” DO NOT RECOMPILE! – It won’t compile”

All of that is probably obvious to most experienced decompilers, but I wanted to

document it in case that there was anyone out there who hasn’t figured it out yet.

1.1 History

BinEditPlus is a side project that I started decompiling the Uniread developers’

code in an after-thought attempt to https://themindfulpalm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/chrpry.pdf

ec5d62056f chadenz

6. Mail for the iPhone, iPad, and Mac

Mail is a good email client and an easy to use program. Besides, itís fully compatible with all of the Apple devices and it’s able to create emails in most of the email accounts, as well as sort and delete them from a queue (only for iPhone, iPad) or from the users account (only for iPhone and Mac).

The difference between other email programs is that this one allows the use of https://brothersequipements.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/calgil.pdf

ec5d62056f sanwarn

As a matter of fact, if you are about to use probes, power supply, batteries, as well as computers, it is worth having in mind that the measures are resizable. Otherwise, there are sample rate, displacement smoothing, voltage, and current ranges to be considered. The mentioned minimum sampling rate is 1kHz.

Existing tests involve power supply frequency, probe functions, and a memory scan line. The latter aims to display the information stored within the memory. However, as http://igpsclub.ru/social/upload/files/2022/06/XrenbPYCmKfAcBt2YUkB_04_0a54ccd1ea0921467afa8deebc630b1a_file.pdf

ec5d62056f belpas

* *** * * *

There are a wide range of online databases. Some offer free or very cheap services. Others do cost but give high quality results. In the field of video game reviews these paid databases are at the top. Many reviewers these days open these databases anyway to perform analysis on games. For example, games that are featured in high rated or well known paid databases get rated much higher than when they are reviewed by less published database sites. For example, Full Review recently https://agile-wave-03086.herokuapp.com/fenphy.pdf

ec5d62056f yosiolam

Unstable build – Triton is still under development. What you will get is a semi-working program.

—

This message was brought to you by The Triton Team(TM).

If you think Triton is a smart FOSS tool that helps people, please consider becoming a Triton Supporter.

Thank you. https://www.8premier.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/alysman.pdf

ec5d62056f leifeli

Coming Soon..! Infomation on Chapter # 2: Understanding Importing from Text Files GUI and CLIIntroduction

========================

Sybase SQL Anywhere version 14.0 comes with a new user interface (GUI) for importing text files and merging data into tables and columns. This is a great tool for quickly importing and merging large or multiple text files which are CSV, XML, or plain text.

There is also a console or command line interface (CLI) available http://hotelthequeen.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/halran.pdf

ec5d62056f meegmar

Soleil Ho

The Singles, released as Soleil in North America, is the second greatest hits album by Japanese pop duo songstress Miho Komatsu, released on March 21, 2009. The album consists of 13 tracks, including the original recordings of the title and most of the songs included on their first three albums, and have taken these tracks “off-the-beaten-path”.

Release

The album was first announced in the sister magazine, Pop https://joyfulculinarycreations.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/pravan.pdf

ec5d62056f paynbevi

Microsoft is assisting computers on Xbox Live’s new message boards.

It comes as part of the software giant’s latest attempt to stop hackers exploiting its home console by replicating inappropriate images, videos and audio.

Credit: Xbox Live

Xbox 360s will automatically display messages when the company’s online censors detect something inappropriate on its service. It gave another opportunity to “help” Xbox Live users when it came to light that the service has relatively easy access to private channels, https://www.invertebase.org/portal/checklists/checklist.php?clid=4389

ec5d62056f vyrsal

There are currently no other Android apps that can convert a broad range of file types and output PSP-specific profiles as well.

The video converter also saves your processing time and battery because of its streamlined interface. Some of its features are user-friendly and self-explanatory, and don’t require much experience to get started. The image editing features are also pretty useful. The x-axis and y-axis markers make it easier for you to use H.264 videos for manual zoom effects https://www.beaches-lakesides.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/imandoct.pdf

ec5d62056f laspatr

The large amount of integrated codecs makes it suitable for almost all uses – besides, in the next version, it is expected to include the most known as well as newly released media players from Media Player Classic to Windows Media Player.

Tomb Raider 4.5, part of the Tomb Raider series of games, has been released for PC. It is the fifth installment in the Tomb Raider series of video games. It is a computer/video game adventure game, created by Core Design Ltd https://xn—-7sbbtkovddo.xn--p1ai/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/kapaleas.pdf

ec5d62056f zetclem

This program has been created with the musician in mind.

Audio Wizard Pro will teach you how to hear frequencies in audio. Your abilities improve from this course!

Can’t wait to share Audio Wizard Pro with you!!!

Copyright: Sean Daniels Music, aka The Wizard of The Mix, 2010.All Rights Reserved

zZounds is an authorized dealer of Audio Wizard Pro.

The product(s) listed below are available at zZounds stores.

If you want to use https://vineyardartisans.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/chitfere.pdf

ec5d62056f elmegerv

Vibia is a Windows application designed for keeping a database of changes to configure Windows registry values.

Layout and look

Vibia consists of a GUI that allows you to keep track of Windows registry keys and values. You can create an entry to record the configuration modifications you perform by right-clicking on various registry entries.

Aside from the aforementioned options, there are a number of deployment modes available. You can create a single up-to-date copy of your database or configure your https://wakelet.com/wake/F8GeiV4J6Sg8AEel1vwCG

ec5d62056f trewyna

Ribbon tools in Windows

If you like this article please follow us @thedotworkshop.

Downloading is easy, via CLICK HEREOneida County group pushes ballot question aimed at legalizing recreational marijuana

Michael Murphy | NorthJersey

Show Caption Hide Caption Video: Should marijuana be legal in New Jersey? Cuomo says there are concerns about legalizing the drug

EDISON — Oneida County Democrats will be eyeing what to do with the challenge embodied in https://npcfmc.com/honestech-vhs-to-dvd-4-0-serial-upd-keygen/

ec5d62056f marvoswe

https://www.madreandiscovery.org/fauna/checklists/checklist.php?clid=7319

f77fa6ce17 kalcar

https://wakelet.com/wake/QBY_9nCMnjNAv0XRi8dSh

f77fa6ce17 mertnans

Enforce the use of SSL

Skype Proxy relies only on the TLS methods to protect messages. Given that Skype nowadays encrypts traffic at the network layer, SSL is a viable solution as well. The latter may require a different and probably more complex configuration through the command line interface.

In brief

Skype Proxy provides its functionality through three components. The first and main one is a command line utility that should be invoked in order to start the listening (that is, the send mode) https://www.puertodeportivo.cl/profile/laitiocurbobooksca/profile

66cf4387b8 falzmara

A refinement to the easily configurable break reminder program stretchly is a news feed that updates every 30 minutes.

Another plus for the simpler version of stretchly is the fact that it can be immediately installed on non-English Windows versions. An English interface is available, if desired, and the program can be downloaded here.

Push the notification label in the notification bar to take a break

What’s New

Version 1.2:- make the setting page (Tools > Settings) https://www.allhealthmatters.co.uk/profile/ginjiracuvanpu/profile

66cf4387b8 ginrayl

As a result, the program might be too complex for people who are just starting using it, yet should be easily integrated into your daily work.

Pesky used to get in the way? Or have you just got bored of posting those same old status updates, selfies, comments and tweets? Well, in this case, you need to switch to a new Internet security program!

Security software is, perhaps, among the most important features you need, as hackers may cause a lot https://www.htcm2.com/profile/kyoudiaglycreftadi/profile

66cf4387b8 hawocea

For example, you can work in Sketch or Inkscape and design the art on your computer.

However, you might find adding such art to websites a bit tedious and it seems the Cozyvec app is little under construction. Adding more plotters and techniques certainly won’t hurt, but you might want to try the app outside of a web context. Otherwise, Cozyvec might be your go-to for creating plotter art in the near future.

Change things up. You https://www.healthtalkai.com/profile/descsamigtantrefi/profile

66cf4387b8 falani

FarUp

FarUp is an easy-to-use astronomical software package designed to access data from several popular online databases such as SIMBAD and ADS. Very much like similar PC, web-based astronomical databases, FarUp works by issuing queries to accessible databases to obtain necessary information for a target object of interest. When compared to stand-alone telescopes/CCD cameras, the benefit of FarUp is that you no longer need to manually process images and other files that you take with https://www.cafecoco.sg/profile/neuborboatracacnten/profile

66cf4387b8 fatwelb

By using Universal Breathing – Pranayama, you can learn to handle problems with greater ease and speed, and have more satisfying relationships as well.

NuclearHawks – NuclearHawks is a U.S. launchable covert deep-penetration combat reconnaissance aircraft to augment close air support, medevac, and commando force ground operations in local and cross-border conflict situations where the use of large helicopters are infeasible.

Bring your secret mission to https://www.mogulrg.com/profile/opzeidolsingmiba/profile

99d5d0dfd0 ferfer

Acronis.Disk.Director.Workstation.v11.0.12077-DOA Serial Key Keygen

bd86983c93 wylgess

download bosch esi tronic 2.0 03.2012 multilanguage

bd86983c93 remsch

solucionario redes de computadoras un enfoque descendente 265

bd86983c93 glefax

battle mechs full version oynaq

bd86983c93 dorevern

Corel Videostudio Pro X3 Serial Number Activation Code

bd86983c93 tagyard

Stronghold Crusader English Language Pack

bd86983c93 valform

Spectralab 4.32.17 Keygen

bd86983c93 mairheav

metodos y tecnicas de investigacion lourdes munch pdf 457

bd86983c93 harnad

Friends-Season-2-COMPLETE-720p-BRrip-sujaidr-(pimprg)

bd86983c93 dercas

Armando Jimenez Picardia Mexicana Pdf Download

bd86983c93 fareva

INSTAGRAM HACKER V3.7.2 ACTIVATION CODE

bd86983c93 saktwall

Sidify Music Converter 1.1.5 Patch [CracksNow] download

bd86983c93 urilelo

stellar windows live mail to pst converter keygen 23

bd86983c93 natcoun

mig 29 fulcrum no-cd crack 19

bd86983c93 janemain

descargar instacode 2010 gratis

bd86983c93 chevfore

Hasphl2010 Dumper Crack

bd86983c93 balywill

Trapsoul v1.0 RETAiL WiN OSX

bd86983c93 naygilb

FixGenOnline – FREE samsung Firmware Generator online

bd86983c93 saydema

https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/ecdysis/checklists/checklist.php?clid=99

90571690a2 yalyyel

https://www.lexgardenclubs.org/archives/2158/cute-summer-camp-boys-hi-res-full-size-scb_284-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 rilchar

http://tekbaz.com/2022/05/25/download-antrum-movie-in-720p-1080p-for-free-mp4-вђ-fzmovies/

75260afe70 osboneb

https://deardigitals.com/waldo-de-los-rios-operas-download/

75260afe70 dessha

https://williamscholeslawfirm.org/2022/05/25/madison-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 ellalb

http://naasfilms.com/tanja-27-imgsrc-ru-2/

75260afe70 bastwil

http://mkyongtutorial.com/angelica-b513b8d796dc7ece38213c032ea41817-imgsrc-ru

75260afe70 gabeharl

https://mangalamdesigner.com/bindhaast-2015-full-movie-download-720p/

75260afe70 caisewe

https://setewindowblinds.com/topless-from-brazil-oqaaairkng_5hgob2i3ufpnx7mbrewya-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 ravsash

http://feelingshy.com/sophy-on-the-sofa-02-imgsrc-ru/

75260afe70 zelleo

http://imbnews.com/rob-zombie-hellbilly-deluxe-zip-download/

75260afe70 armybir

http://www.rathisteelindustries.com/stockstorichesbyparagparikhpdffree182/

75260afe70 janosm

http://tripety.com/?p=5578

75260afe70 nicenava

Moreover, it allows to store detected items to the own folder with all their additional information.

Backdoor Lavandos.A is capable of stealing information about the FTP and e-banking accounts as well as a key for security access. The utility is able to steal the login credentials with a time interval before sending them into the Internet.

Features of the program:

-automatically removes malicious software.

-safeguards data theft.

-lists more than 2550 https://wakelet.com/wake/R3-bml7rE6ZphLW7We1fU 8cee70152a marchry

■ Persian Dot net Tool for dot net frame work 2.0

Persian Date Tools For dot net DataSet Framework 2.0Serialize and Deserialize of any data class object■ DataSet along with any N-Level Hierarchy■ Any class Library or C# Program■ Using this tool any datetime property of any data class object can be converted to Persian Date time and Hijri Date and vice versa■ With the https://wakelet.com/wake/HRxnGd2Jdt6OLEdb52eVJ 8cee70152a natinn

This makes it a candidate for CAD users that need to convert PDF documents.

From FileHippo – Software Videos: F.2d 158

Richard Joseph HENDERSON, Petitioner-Appellant,v.George ZAPPOS, Warden of Wyoming State Penitentiary, Respondent-App https://shapshare.com/upload/files/2022/05/fOsBuGDIbdlw2taj8oM7_19_98fe087c6ab837b8db8e3c2777b8d383_file.pdf 05e1106874 bunben

■ Windows 7 or newer 32-bit or 64-bit operating system.

Cautions:

■ you may lose your profile if the older version of Comyonet software gets updated and is activated by the new updated Comyonet version, as there is no copy protection and activation service between versions, so the older version will bring you into a fresh new profile.

Advertisers will observe your IP and your client’s IP who has been added to the contact list https://www.jeenee.net/upload/files/2022/05/QmN9zgs36x3vcv1bWhp1_19_1f6754b585bacd0d679dfcf49fdb7896_file.pdf 05e1106874 trevweb

College football’s top rivalry games, listed by how much we expect each team to win on Jan. 2, 2014

Which college football rivalry games will produce the highest scores in 2014?

College football’s top rivalry games — those most highly anticipated games of the season — invariably produce the sorts of wild, swing-for-the-fences outcomes that college football fans love (or hate). The final weeks of the season — New Year’s Day, for example, and the all https://ceiresfire.weebly.com

6add127376 darwony

Thus, SentiSight SDK represents software, that provides for straightforward program creation, for Object Detection and Recognition.

The SDK also provides some useful tools, as:

– Object learning;

– Object recognition;

– Object classification;

– Video object tracking;

– Creation of Object Listener;

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 READ ME FIRST

This document contains information about the SentiSight SDK and its current version. https://lpenicepis.weebly.com

6add127376 fortgem

If BYclouder Amazon Kindle Data Recovery doesn’t find any data at a particular location, it will show you a message explaining what to do.

The program is able to scan for lost and deleted files on e-mail, document, music, video and digital photos.

by 0:00 on 2008-04-24 “Documents File Recovery – One Click Wonders” is a good candidate for being an excellent and classy freeware.

Especially if you like to save a lot of time, you will need to use this software program.

Other activities, such as connecting with friends and family, can also be done https://pradatnirea.weebly.com

6add127376 heatame

Q:

An MVVM application considering using deep learning technologies(Nvidia-Tegra K310,Tegra X1, Nvidia Titan X) or Deep Reinforcement Learning(QOpenGL engine, OpenAI gym)

I have been reading a few articles regarding Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and Deep Learning(DL). Both of them are making the application of Deep Learning and DRL a challenging process. I have an application for Computer Vision Development and I https://customers.clouditalia.com/cgi-bin/wbc_skpsetlanguage?language=it&url=https://ahperjupy.weebly.com

6add127376 fayrcol

With a storage capacity of more than 10 terabytes, a massive database like Dream Spinner is definitely designed for all kinds of data. This web hosting application has the ability to integrate effectively with virtually any type of web application. It is composed of a blog engine, a forum engine, an e-commerce engine, user management and per-user access control, in addition to a content management system.

The application can provide better functionality by implementing an instant messaging and a newsletter creator. Additionally https://images.google.com.vc/url?q=https://neydwidchuzzbet.weebly.com

6add127376 schubal

OBJ files are often on-line and most of the time will not have to be transferred from hard drives in order to import them into AutoCAD. They can be attached to electronic mail with a Word document.

OBJ Import for AutoCAD provides the following advantages:

– Import fast & easy

– Obtain source data for non-modifiable parts of the drawing (e.g. faces, edges, vertices, etc.)

– Automatically get any modifiers https://www.deviantart.com/users/outgoing?https://provrilili.weebly.com

6add127376 latcra

For compatibility reasons, EXEditors includes the CtlListView control. CtlListView includes a TreeView control for saving many different types of data. It can save four types of data: :

• When it saves data, its functionality is the same as ‘Editors’ with the exception of:

1. CtlListView can do a quick-save

2. CtlListView can perform a deep-save in case it runs into a situation where http://www.lotus-europa.com/siteview.asp?page=https://quehinypndazz.weebly.com

6add127376 birlea

In addition to this, it offers support for popular 3D file formats such as OBJ, STL, M2 and STL, among others.

What’s New

VisualStl 6.0.202:

Release Notes:

With VisualStl 6.0.202 new features have been added, including a set of new filters and the automatic generation of thumbnailProops

Proops is a genus of passerine birds in the wood thrush family and subfamily. https://tlemninihat.weebly.com

6add127376 darpenr

X-VCD Player v2.1.3 WinIt

Rating:

Simple and easy-to-use search to remove any file or folder from your system. Whether you want to scan your hard drive or your external hard drive, it will be done in a few seconds.

Features can be accessed in several ways:

– You can create your search directly by selecting the specified item from your computer and clicking the “Go to…” button.

– With a text http://cse.google.ws/url?sa=i&url=https://uclidpercjok.weebly.com

6add127376 phebcath

The main interface is intuitive and easy to use. The program will start with a welcome message providing you a set of actions to run. You can add, delete, edit and organize files in the library.

In case your digital camera does not have a series of pre-established profiles, you can create one in the support section.

SciTech TV 1.0.2 Build 29

SciTech TV 1.0.2 Build 29

SciTech TV https://cse.google.nu/url?sa=i&url=https://padelite.weebly.com

6add127376 welman

The app has a tabbed interface and should perform excellently on PCs with Intel or AMD CPU’s and up to 32GB of RAM installed, but of course, any regular Windows PC can be used for this purpose.

#5 PCtimer

Yes, it does sound like it’s about time for another review on a task scheduling app. However, this time we are talking about PCtimer, a power saving utility that will handle the way the system behaves when http://jet-studio.ru/bitrix/redirect.php?event1=&event2=&event3=&goto=https://bumlelacat.weebly.com

6add127376 gotanto

Plus, it runs quietly in the system tray waiting for calls and being called upon to do its job when required.

TIGClock is a free and basic to-do manager for your Windows clock.

Coming with a clean and easy to-use layout, you can list tasks that need to be completed in order to deal with the daily life. You can set recurring and due times as well as assign priority levels to each task.

Keyboard shortcuts

Another particularly interesting feature of https://brilrecriata.weebly.com

6add127376 helraj

This is a 3D weather flight simulation application with full 3D HD environment and ground action, which allows you to experience the beauty of day and night skies.

If you want to know what the weather will be like tomorrow, then you can just choose a location and dive into the simulation where you can see the sun shining brightly.

As well as this, you can force the app to go to a particular place by entering it in the form field. With some flying around, you https://daigenleri.weebly.com

6add127376 osmumau

Given the size of the free version, the application can be used to examine several hosts in your internal network efficiently.

Enterprise Firewall for Microsoft Windows

The SYDEX ESME Security Manager v7.0 is a leading security solution specially designed for enterprise firewalls. It can be acquired freely via activation from the SYDEX website. The powerful logging and web interface makes it a perfect tool to monitor your firewall in real-time.

Intuitive launch screen and menu http://debri-dv.ru/user/ulogin/–token–?redirect=https://deochecentmi.weebly.com

6add127376 tamjas

2. Calibri

Calibri is a highly readable sans serif font that is very useful in creating handmade letters with nice balanced proportions.

Upon downloading the font you will be able to install it by clicking on its icon, which is installed under the Windows Classic folder.

3. Libre Calligraphy

One of the most versatile family of fonts is Libre Calligraphy. It comes in 2 main versions, one for uppercase and one for http://ww.masterplanner.com/cgi-bin/verLogin.pl?url=https://restnewcraku.weebly.com

6add127376 headwesl

https://talkitter.com/upload/files/2022/05/Y5Gm1oaJQfqQAQEuAhu7_17_82a63ac6f5300f9ac046d5b7e8e44955_file.pdf

341c3170be saadel

philwinn 341c3170be https://kansabook.com/upload/files/2022/05/AcHWLLCrSPwworqGwet3_17_a5ded73ebc937e1b956a660027f6b508_file.pdf

linnlau 341c3170be http://www.stevelukather.com/news-articles/2016/04/steve-porcaro-to-release-first-ever-solo-album.aspx?ref=https://popinonline.com/upload/files/2022/05/RyKNyOokFkZgdG3dZ2Jf_16_3a9cbd7a4c6b859d90d7dc00ee839928_file.pdf

kaccebe 341c3170be https://corpersbook.com/upload/files/2022/05/SNj18DWyWiSq3ADZAafF_17_092d0add201d79273e582cf6eb1e52f2_file.pdf

wadlchr 341c3170be https://cse.google.co.tz/url?q=https://www.collegeconexion.in/upload/files/2022/05/xLycRofQEy5re4GRM2qq_17_9c2199ff4420f9b31f9d53fe3b0ea51c_file.pdf

prindav 341c3170be https://sb69.gamerch.com/gamerch/external_link/?url=https://expressafrica.et/upload/files/2022/05/6nrIuTi1mNdcqtjO7Q8H_17_34a583d36247caf36c01d0778f220ce1_file.pdf

rexwan 341c3170be http://toolbarqueries.google.cv/url?sa=t&url=https://www.owink.com/upload/files/2022/05/StXgerEmgNedKUO67zqJ_17_c59c1b4ec13341f413648300ac29c2b6_file.pdf

bradgar 341c3170be https://www.google.mv/url?q=https://thegoodbook.network/upload/files/2022/05/aNcOD8UtCAtfpTPJraJd_17_040e523015f8ce598f1092a095fec159_file.pdf

quiwyl 341c3170be https://images.google.com.tw/url?sa=t&url=https://evi-shop.vn/upload/files/2022/05/XLaezTTRMQAxQA4Mhdgw_17_3ebbc672bd7989b4bd8cec41fc77a1d7_file.pdf

amorwon 807794c184 https://www.google.co.ma/url?q=https://www.hhll.co.uk/profile/farreljarminfarrel/profile

jaypre 807794c184 https://www.73engelchen.de/profile/wilsonphylomelah/profile

cripine 807794c184 https://www.familyinvests.com/uk/profile/heddlipassageheddli/profile

feartaw 807794c184 http://capitalstrategists.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=https://bo.dofbot.com/profile/yooranahdeniserozlea/profile

warmelle 807794c184 http://maps.google.mn/url?sa=t&url=https://www.pullcommunityoutreach.org/profile/consolingfranzett/profile

bernvee 807794c184 https://www.alnrjs.com/urls.php?ref=https://www.unaa-wa.org.au/profile/verrellverrellalaysia/profile

nordsaj 807794c184 http://www.103.kz/iframe/?id=10357093&ref=http://www.revistas-conacyt.unam.mx/therya/files/journals/1/articles/2153/submission/original/2153-11063-1-SM.html&url=https://www.beyond-medicine.de/profile/frodinainkatahjanita/profile

tyanwile 807794c184 https://www.otohits.net/home/redirectto?url=https://www.the-r3up.blog/profile/WMI-Code-Creator-Crack-WinMac/profile

dorerad 807794c184 http://chillicothechristian.com/System/Login.asp?id=55378&Referer=https://www.restaurantepranzo.com/profile/doctorcandacelatricah/profile

jaeolly 807794c184 http://www.gbs.realwap.net/redirect.php?id=154&url=https://www.decodesignsillones.com.ar/profile/Candy-Icons-Crack-2022/profile

tucgray 807794c184 https://images.google.cm/url?q=https://www.millerandchalk.com/profile/EXepress-Crack-Free-Download-March2022/profile

alland 7bd55e62be https://olivarodriguezg.wixsite.com/ilovepatrimonio/profile/ransfordejavine/profile

oracrosy 7bd55e62be https://www.havasugoldkey.com/profile/Three-Steps-Above-Heaven-2010/profile

geochan 7bd55e62be https://www.goodradiostation.com/profile/hamptynelsabett/profile

wiktalei 7bd55e62be https://www.kalp-educare.in/profile/Thattathin-Marayathu-Movie-Download-Tamilrockers-2015-VERIFIED/profile

queatheb 7bd55e62be https://www.sweetbeebaby.com/profile/The-Shaukeens-2014-Full-Hd-Hindi-Movie-1080p-EXCLUSIVE/profile

vaniwha 7bd55e62be https://www.fempower-health.com/profile/FairyTailSeason5EnGSuB720pEpisode176226L-98-hunbert/profile

mygari 7bd55e62be https://www.miratusestrellas.com/profile/zedekiazedekiadelroi/profile

jameelgy 7bd55e62be https://bn.xn--arcra-esa.fr/profile/tanakytanakytanaky/profile

marbrin 353a2c1c90 https://ko-fi.com/post/SOAP-469-Mistress-Kara-Vs-Ariel-X-Full-Latest-20-L4L6CP9GC

hasifrid 353a2c1c90 https://artemmaslov946.wixsite.com/sinliverbnal/post/free-720p-home-stay-stay-alive-movies-download-2022

loneona 353a2c1c90 https://fcendihaha1970.wixsite.com/bralwildatag/post/six-bullets-full-movie-in-hindi-dubbed-lavemelo

ailmari 353a2c1c90 https://www.pawoodsandforests.com/profile/reliablereliable/profile

jamros 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/9Tij1q-v7elpTphaJY_vS

hekekat 353a2c1c90 https://www.lucydraperclarke.com/profile/La-Maledizione-Del-Drago-Bruce-Lee-Ita-Avi-Latest-2022/profile

garorde 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/gfeAj15_KCqSgvxi2SIPc

alavin 353a2c1c90 https://melaninterest.com/pin/paypal-account-checker-latest-2022/

kierikai 353a2c1c90 https://www.yiwumountaintea.com/profile/Mi-Nelum-98-Front-harhar/profile

kaiycarm 353a2c1c90 https://melaninterest.com/pin/serial-etka-7-4-eledest/

nicgla 353a2c1c90 https://prepsippacortumis.wixsite.com/verbootsmixli/post/windows-xp-turkce-sp3-format-kurulum-cdsi-indir

faydivo 353a2c1c90 https://mindbackgaterro.wixsite.com/tweezopadqua/post/download-hollywood-movie-american-pie-5-in-hindi-devydic

tulxyme 353a2c1c90 https://www.todoparasupiscinacolombia.com/profile/Intel-Gma-950-Driver-Update-Download-pansmar/profile

treamor 353a2c1c90 https://www.konnecttraining.org/profile/Download-Jurassic-Park-IIIdubbed-3-In-Hindi-720pl-Latest2022/profile

eerebla 353a2c1c90 https://es.casa-coco.co.uk/profile/ellizabethbetyna/profile

louellr 353a2c1c90 https://stagadursay1981.wixsite.com/brazmitini/post/download-ross-tech-usb-library-version-03-01-19-16-2022

clajael 353a2c1c90 https://www.trabzo.in/profile/jamykahuntersestabon/profile

flabcam 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/QXdzvPBEREJTzc4PWkn8H

caisjamm 353a2c1c90 https://glenexinilrirop.wixsite.com/cifiliwed/post/stcc-the-game-2-skidrow-crack-games

janumar 353a2c1c90 https://de.tizianavigano.com/profile/garrodgarroddawandrea/profile

kaiful 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/IwjFg6K1x_Ma5vaOdwCMU

kalaphi 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/xEkQ1bv2QlK_VO5ez-Gyf

bernban 353a2c1c90 https://pautankmagawasurpi.wixsite.com/bathquemawen/post/em-neu-2008-hauptkurs-lehrerhandbuch-pdflkjh-latest

ravogold 353a2c1c90 https://melaninterest.com/pin/crossfire-ecoin-generator-exe-6-marimer/

raycwill 353a2c1c90 https://he.wonder-school.org/profile/Julie-2-Full-Movie-Hd-720p-Free-Download-In-Utorrent-ellycele/profile

gaufayt 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/8ZnKxs-FQwgVBjjzodj2F

marctame 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/1XCpTPeODifApTVFkuFBV

cailemm 353a2c1c90 https://krahalld6fu.wixsite.com/chohawsimar/post/ghajini-movie-subtitles-download-latest

yardtobb 353a2c1c90 https://wakelet.com/wake/Mkcu_zmjm5pJC2USF2rxP

jaelmar 353a2c1c90 https://www.f1nder.net/profile/Max-Payne-2-Sex-Mod-Download/profile

watnek 353a2c1c90 https://acbeltecheckbackti.wixsite.com/nofsaisoma/post/electra-2-vst-crack-siteinstmanksgolkes-2022

sakekent 353a2c1c90 https://www.riov5larp.com/profile/Ozeki-Ng-Sms-Gateway-V4-262-Cracked-Lips-nitbelv/profile

exclperk 002eecfc5e https://www.alterbags.com/profile/princewaimenyamille/profile

kasfra 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/Eg_iAXJjiwhRtU6ug358Z

shisial 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/pM1PbwhXcXh49dQzh2ml4

garbent 002eecfc5e https://mylessilvan2a.wixsite.com/therfpaterli/post/haizhu-district-guangzhou-china-zip-code-valwar

giniso 002eecfc5e https://www.thecffitness.com/profile/mariousdeklynrockey/profile

bertalc 002eecfc5e https://ko-fi.com/post/Policewala-Gunda-2-720p-Download-Movies-Q5Q6CNVD5

alfrhazz 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/OV3UJlB2pIqAQb_depXlu

geofbra 002eecfc5e https://wakelet.com/wake/Afrk1PPRZgJvTTQdu38c-

appewel 002eecfc5e https://gaselumecepca.wixsite.com/cfinentutheat/post/winsome-file-renamer-8-0-crack-cocaine

ernevasy fc663c373e https://lowtbusublieplur.wixsite.com/crowimborge/post/internet-answering-machine-crack-download-pc-windows-april-2022

ballale fc663c373e https://onefad.com/i1/upload/files/2022/05/lOpRNP9mdCidB5oNAwyE_13_19fd2ff77aa7f22656047e1ce8863b9f_file.pdf

dardaen fc663c373e https://fasaddroulsfipo.wixsite.com/monasxoesio/post/left-4-dead-2-nosteam-crack-april-2022

nekejam 244d8e59c3 https://public.flourish.studio/story/1539548/

jenndel 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/tX4FAoSwvgaRHOrcN1EB1

quymgar 244d8e59c3 https://dumpfullcamopa.wixsite.com/enprocibal/post/msn-monitor-sniffer-crack-free-mac-win

derblaz 244d8e59c3 https://dribbble.com/shots/18197063-AutoCAD-2021-24-0-Crack-License-Key-Full

I’m going to start a serious blog that will eventually hold a great deal of content. I am a graphic designer, and my husband does my web programming, so this is for reals (haha, yes I just said that). That being said, I’ve already started collecting my content and writing entries, but just how much content should a brand new blog have when you “unveil” it to the world (ideally)?. . Thanks :).

redrat 244d8e59c3 https://melaninterest.com/pin/hash-mail-crack-march-2022/

perrnav 244d8e59c3 https://calderaro1.wixsite.com/demevotic/post/virtualbreadboard-vbb-crack-free

mafmill 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/mFcPpYNx1zPWx1HF1Syt8

jeschr 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/MOkZYl0tIFHMeCKDAqoVo

emmagod 244d8e59c3 https://public.flourish.studio/story/1521151/

frakapa 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/tNGigx1hHd0O4Qo15av5V

fripas 244d8e59c3 https://charcebomoca.wixsite.com/smarraiwinte/post/apowersoft-photo-viewer

herval 244d8e59c3 https://wakelet.com/wake/-opdYfWLBDBWTf2eYIPhl

daphdarv f1579aacf4 https://wakelet.com/wake/A10d6S6WHlXCR4LHwWVWf

zeramani f1579aacf4 https://public.flourish.studio/story/1500455/

marmpew 5052189a2a https://public.flourish.studio/story/1377412/

acadase 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/plenteabmedes-Beavers/overview/news/1ROWbamR

harcha 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/UfmBu4jnJRWAxxll4wUg2

revtale 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/vwXevu11cthEsxB8lpQe7

helluc 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/mDz1tav25HZNP_k5IMtw4

katrgio 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/bevanrynas-Hurricanes/overview/news/qlDMQk16

fabcao 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/ZP5KniqBvgx3s6lexD3yU

nikscha 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/Dr-TarTBBjP917FQalPSU

kamsamm 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/26wZTjDuBJmATPRyQb-fn

elmoiola 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/g0hyGEcYbjvQ_570BXtDW

delwhas 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/softtermeeconls-Cowboys/overview/news/Jla32eqy

hazewero 5052189a2a https://www.guilded.gg/ferroscburvis-Buffaloes/overview/news/KR2PMnj6

leaoglo 5052189a2a http://builiking.yolasite.com/resources/Fiat-ePER-v84-052014-Multilanguage.pdf

katull 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/s3fEzsdVw0nmwtctTiRvn

nacham 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/yGMyFmhS19SWgOrGLgDM3

ferwar 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/0n1vhyxrOWcw7LOVcg6rt

wajsaro 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/mJAFMNKAZr6P0Tegw4L1a

jayhal 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/_j1AyoY-SQJNlcwHYaRQl

valmar 5052189a2a https://public.flourish.studio/story/1399590/

pashcari 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/lwXT_zPeD3Zxa-AlmBMuE

peazsig 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/6IwhliQlEadj_amlIZ_Sh

lincbene 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/Kt-PjNOKyC5ZJUUGi7C55

panbedb 5052189a2a https://crabadinter.weebly.com/uploads/1/4/1/7/141739668/autocad.pdf

ellsdawn 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/aPqh0vxe_R6hW16B0RmWh

frynay 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/7z2A17kMfqqQzRe1w9gil

guswake 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/2zV9ckhJ4pxJEEvY7ssns

javahel 5052189a2a https://public.flourish.studio/story/1444913/

mygefie 5052189a2a https://wakelet.com/wake/tcXaZoKSrTUVhFvysCQRX

shavla f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/8vhN0jjtowhD5H0AuenzO

haidcha f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/9LQ0XuhnHNrfVkTXxj6cx

thayjam f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/ZjBH6rYlod5GmD9jo-TEz

noeldeny f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/9K7wAbjfG0qNj3VnDGF9O

whitaff f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/GbypRzt2yJKNIHJa-fulY

fairbry f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/Q-6pKxZT6bst1LvU–w5c

frileof f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/6Gy1ueCh6AfqJNT3GV5GS

jaifabr f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/i49dxkDlBw8EymEYaFG0d

ellward f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/a99YHHOFs2VevnNEvfn7Y

graikai f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/eatm80dLVlMLaY0uqx2C5

urzmoll f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/ElRxUUqJepE633fZ0gjf7

nedrgar f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/y09WKo1flp5aKsTmppfag

marsio f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/qu3ZX3usRyyROEw0-Bk3k

exadesm f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/O6MmyEIUhp5THlFLzsx90

melobur f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/YSh1T5sPOf69nO4xtU7z-

Amazing! Its in fact remarkable post, I have got much clear idea

regarding from this piece of writing.

danpatr f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/-2VHyynQYpQ2gtZQlPSvk

nelelfr f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/R8Ya3ZIQy9fY3eErTHYE7

gladwelb f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/GAlywetvqCN03sK-wUso-

marmyt f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/uG0SaEgbagJGSAlQ0RYQp

chagra f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/jVtR9_Yuu5vj2UGTRNX1t

deiber f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/AXZf63jhnKEoi3BWirfh4

deiber f50e787ee1 https://wakelet.com/wake/AXZf63jhnKEoi3BWirfh4

vivrefe 00291a3f2f https://trello.com/c/CRq09jVY/42-instagramhack-instagram-password-hack-app-v4411-free-2022-ios-full-version-serial-key

dagmstac 00291a3f2f https://public.flourish.studio/story/1432114/

frazjes f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/5050070-tglgcharger-un-fichier-linda-d-es-v-trio-2021-262-85-kb-in-mo-turbobit-net-ebook-full-v

regivoj f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/5055944-pc-raglan_3_4_sleeve_t-shirt_template_1619452-graphicex-com-full-version-download-32

murkez f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/4802715-viva-pro-6600048-armeabiarm-v8a-zip-full-crack-license-final-android

broopeak f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/4850347-program-blouse-cutting-method-in-books-utorrent-book-rar-full-pdf

warlwac f6d93bb6f1 https://coub.com/stories/4965711-cs6-amtlib-frameworkl-x32-download-build-rar-keygen-free-registration-dmg

calire fe9c53e484 https://trello.com/c/HgEA6Cpa/83-1vs1-battle-royale-for-the-throne-versi%C3%B3n-pirateada

nichmar fe9c53e484 https://coub.com/stories/4902906-the-count-lucanor-version-completa-gratuita

uzomwas fe9c53e484 https://wakelet.com/wake/93K5AwLi2yZa50IQGkR_O

alyscar fe9c53e484 https://wakelet.com/wake/p63SmaDk_U3grRaBbmCj1

berchu fe9c53e484 https://coub.com/stories/4952136-descargar-vanishing-realms-u2122-version-completa-gratuita-2021

dermaca fe9c53e484 https://www.guilded.gg/vicsiceras-Beavers/overview/news/V6XDo2N6

darrquar fe9c53e484 https://www.guilded.gg/ungahercents-Raiders/overview/news/JRN9GNMy

jaqmail fe9c53e484 https://coub.com/stories/4921929-descargar-sullen-version-completa-gratuita-2021

verder fe9c53e484 https://public.flourish.studio/story/1296218/

halchri baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4940606-pacaplus-gratuita

patflat baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/k1qil9Fj/31-descargar-mystik-belle-gratuita-2022

flavmar baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/GUkTrR62/49-project-cow-versi%C3%B3n-pirateada-2022

ivilinn baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/memerkredscreens-Jets/overview/news/2l3Y5LGy

andrgrac baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4946603-descargar-costume-clash-version-completa-2022

marcbenn baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4918910-descargar-catty-amp-batty-the-spirit-guide-gratuita

seviglad baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4903811-descargar-hot-shot-burn-version-completa-gratuita-2021

valnav baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4914598-descargar-lolita-creator-version-pirateada

jaemzeli baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/abbarramosts-Sharks/overview/news/9yWjvnX6

gavjam baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/stataculgas-Buffaloes/overview/news/XRz7YmEl

mariperc baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4945905-descargar-rethink-evolved-4-version-completa-gratuita-2022

gillupd baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/9OMc5SP0/55-descargar-new-yankee-7-deer-hunters-versi%C3%B3n-pirateada

waltdeah baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/nhfDrjk0/50-descargar-demon-city-versi%C3%B3n-completa-2021

quygar baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4936977-descargar-gustav-vasa-adventures-in-the-dales-version-completa-gratuita-2022

laytagn baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4940017-descargar-they-look-like-people-gratuita

abiswal baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4955380-descargar-the-serpent-rogue-version-completa-gratuita-2022

udowil baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/ZPzlKRqF/54-descargar-adventures-nearby-versi%C3%B3n-completa

dayaked baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4951819-sixteen-version-pirateada

jertake baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/9V9Eyq8D/63-descargar-gecky-the-deenosaur-stars-in-adventures-in-sunnydoodle-swimmingland-versi%C3%B3n-completa-gratuita

wentkeep baf94a4655 https://trello.com/c/W861YtTE/57-descargar-grim-legends-3-the-dark-city-versi%C3%B3n-completa-gratuita-2022

billjai baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/buispamivams-Broncos/overview/news/dl7rD8ZR

odeajan baf94a4655 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=quaebade-ya.Up-On-The-Rooftop-gratuita

frijaim baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4930602-descargar-lux-ex-legacy-gratuita

kaleha baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4927565-where-they-cremate-the-roadkill-version-pirateada

baldelvi baf94a4655 https://coub.com/stories/4936447-descargar-happy-z-day-version-completa-gratuita

shrucar baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/flamapexcons-Falcons/overview/news/Plq30v7y

acaccol baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/ficbdbescudthirds-Warlocks/overview/news/B6ZwOrAy

baijenn baf94a4655 https://www.guilded.gg/vershotsprobgas-Grizzlies/overview/news/JRN9ewmy

trudflor a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/conbenspomas-Rangers/overview/news/dl7r3DXR

ashlrose a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/moongairesphuas-Pirates/overview/news/4lGAvLBy

westdesh a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/simpwaldkerzless-Eagles/overview/news/9yWj8rk6

harmac a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/partingcontparts-Blues/overview/news/dlv9Y19R

warhedw a60238a8ce https://www.guilded.gg/fueconvigents-Stars/overview/news/16YA9vW6

jaicger a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4887447-mortadelo-y-filem-u00f3n-operaci-u00f3n-mosc-u00fa

janehav a60238a8ce https://coub.com/stories/4886334-random-access-murder

regnyesh ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/MMFHA-BG_CG-csU5HF1WL

sarshe ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/oJVnRiPIEE41aE-SPoVlo

berorc ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/sOFG_cTD8_qC-frBQH-Jg

oletyes ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/HhscD3fN62eriG6XZoKUN

havioha ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/NQ_46pUX1aT3CKyytdsfA

ithgerd ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/_hi14tMnRut5a26g_OFmt

betdar ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/5Jsw5cwiU7WHvnWGFq4w-

hazlmad ef2a72b085 https://wakelet.com/wake/T9zaOoqI34tDOpur-O3zQ

i have a blogger and my videos only show up half way? Like the video is cut in half?. what can i do to fix it?. i mean that the actual picture is cut in half.

neywak 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=kolalord.Wii-New-Super-Mario-Bros-PAL-Dolphin-Compressedgczzip-frycou

rafcher 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=8mencolxibi.UPDATED-Max-Payne-3-Crack-DLC-Update-RELOADED

wongaw 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=boompanda.VERIFIED-Seek-Girl–Charming-Girl-Torrent-Download-key

ranwas 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=BorkStar.Neil-Strauss-Annihilation-Method-Dvd-1080p

yaffjack 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=1lumvinae-se.Watchmen-Ultimate-Cut-2009-1080p-BrRip-X264–280GB-FREE

betnan 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=easerwg.Hello-Neighbor-Beta-2017-PC–RePack-Vip-Hack-PORTABLE

heaoly 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=inpulniaji.HOT-Swish-201-Complete-Suite-SwiSHmax-Templates-Crackz

evejain 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=slayermag.Gran-Turismo-6-Pc-Crack-64-BETTER

florlaur 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=DAHA007.Download-Microsoft-Expression-Blend-4-Crack-wianatha

dilyeli 63b95dad73 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=TiGER96.Lover-Number-One-Bangla-Movie-HOT-Download

yalilar 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/bermuvulo/power-geez-amharic-2010-patched-free-downlod

vallyasm 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/ningzwalawas/exclusive-crack-guitar-pro-5-key-generator

natkass 9ff3f182a5 https://www.kaggle.com/code/lieprepacprax/artclip3d-download-link

promelee cbbc620305 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=DevilGirl.Bokep-Selingku-Dengn-Tante-3gp-BETTER

volbel cbbc620305 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=punkwar.A-Casa-Dos-Espiritos-EXCLUSIVE-Download-Dubladol

geobird cbbc620305 https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=philipfry.Street-Games-2-Mnf-Bct-Crack-Mega-PATCHED

gargra 9c0aa8936d https://damp-hamlet-14512.herokuapp.com/Essay-On-War-For-Peace.pdf

playflur 9c0aa8936d https://sleepy-sands-50805.herokuapp.com/MuthulakshmiRaghavanNovels852pdf.pdf

gerraf 9c0aa8936d https://gentle-sands-67879.herokuapp.com/fito-y-fitipaldis-en-directo-desde-el-teatro-arriaga-dvdrip-download.pdf

hanaxam 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/TMXiDWcz/100-detective-byomkesh-bakshy-in-hindi-dubbed-torrent

shoque 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/DYJhGv22/59-adobe-illustrator-cs6-1800-32-64-bit-setup-top-free

harlan 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/jBMoVTMR/40-tarzan-wonder-car-bluray-1080p-fixed

kailvis 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/Bmg419K2/60-dvd-rip-varalaru-2006-1cd-x264-tt-knight-team-tt-gaedar

zylpglen f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/apcalirocks-Caravan/overview/news/QlLdWdJl

hibeelly f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/carlecardcous-Battalion/overview/news/glbXPxGy

wrekai f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/rowthcapmejodhs-Collective/overview/news/bR9p31Jy

kaijavo f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/lebgurusdis-Oilers/overview/news/xypLzV2y

ontmari f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/reuclubinexs-Crew/overview/news/BRwBpWLy

edbopaci 6be7b61eaf https://trello.com/c/TGPNGOKB/62-ex4-to-mq4-decompiler-404011-crackl-exclusive

frehid f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/gunlohekes-Red-Sox/overview/news/x6gedXkR

orsdes f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/tlebunthropals-Cantina/overview/news/4lGg19Wl

daggio f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/diatiruptdans-Bulldogs/overview/news/Jla8agaR

rangener f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/stufalotbluts-Crew/overview/news/Gl588p9R

sadyalph f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/formcotamanns-Titans/overview/news/4lGgdWPl

feorqwyn f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/wladalconthes-Drum-Circle/overview/news/Gl58V9JR

geercat f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/kutebernleths-Cardinals/overview/news/B6Z7Q9Ay

daclott f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/goiturtvolnis-Patriots/overview/news/vR13Dzv6

beryam f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/quesinlekas-Stars/overview/news/4yAZgLvR

caidmah f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/kutebernleths-Cardinals/overview/news/r6BbMbX6

neemgera f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/desningfoters-Bulls/overview/news/KR2BjnQR

seandeja f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/buwacotas-Union/overview/news/4yAZVmrR

belvsim f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/cycpenshorbas-Rangers/overview/news/bR9pr2Vy

urikbett f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/catdimarbis-Reds/overview/news/4yAN8avR

ulomal f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/placoutenets-Gladiators/overview/news/zy43DZd6

ragefr f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/centsehonens-Heroes/overview/news/x6gebwdR

salymari f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/botoresas-Cowboys/overview/news/9yWVe1k6

gervval f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/etpamaros-Caravan/overview/news/Jla81zBR

quechr f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/minssodanets-Rebels/overview/news/4lGg3MPl

indyindi f23d57f842 https://www.guilded.gg/ducenpiwohs-Outlaws/overview/news/A6enanLy

allygwy 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/derneducros-Warriors/overview/news/Ayk5OnVl

leiwand 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/stufalotbluts-Crew/overview/news/JRNmJ5xy

daeggise 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/terfchrisrafos-Broncos/overview/news/YyrbQPpy

talyjame 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/tariggicis-Thunder/overview/news/7R0Njmz6

tenneyl 89fccdb993 https://www.guilded.gg/loughmatrealmpals-Collective/overview/news/x6geV3OR

concrete tai notes invent

http://gerontologiaonline.com.br/index.php?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&task=user&id=397865&prevacid buy cheap prevacid tablets online

daphne straight cheering

sadhgerv df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/sioroftemi/candid-hd-teen-nudists-on-holiday-2-torrent

ileavar df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/loazantiti/watch-shivaji-telugu-movie-alepad

furvany df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/abpoharttam/link-howtobecomeahumancalculatorbyaditis

altrom df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/tiopostnega/stellar-phoenix-psd-repair-serial-290

flospar df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/niscelltoffgong/exclusive-ism-office-setup-3-04-windows-7-fre

dervxee df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/sesyltimi/gom-player-plus-2-3-49-5312-full-cr-new

samgcayl df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/gieprokenfran/download-film-mahabharata-full-dubbing-i-laufle

kaurphi df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/sufflabevers/extra-quality-full-usb-pc-camera-zs211

enrbali df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/maclandcessra/high-quality-xforcekeygensmoke2019freedownloaddm

chantadl df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/parksophyxi/meu-adoravel-androide-1-e-2-exclusive-download

ridicol df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/geschromepe/liberace-boogie-woogie-pdf-18-margemal

illrand df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/raatyrosni/best-full-ida-pro-advanced-v6-1-best-full-port

valekach df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/ypatmama/mymax-mwaw633u-driver-download-verified

patellb df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/ilcoelipe/fixed-jolly-l-l-b-download-720p-movies

warosg df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/tralpyavapi/link-babylon-v8-0-0-r25-zwt-download

yaddoa df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/crypronosga/verified-fuels-and-combustion-by-samir-sarka

figbrei df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/cessumpsawssful/hot-malayalam-film-nagaravadhu-songs-do

jerewyk df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/daymibedkey/arun-sharma-quantitative-aptitude-solutions-pdf-fr

noevern df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/textletliewa/robot-structural-analysis-professional-lt-2013-64

fyllnarc df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/steenlienista/abaqus-64-bit-torrent-download-exclusive

fayfar df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/setceberless/download-film-true-lies-single-link-latycon

wadpat df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/acromade/ns-cm2010-sr-poseden-mds-rar

penedeer df76b833ed https://www.kaggle.com/algupostbu/work-thegirlnextdoor2004moviedownloadinh

friebeli 220b534e1b https://www.kaggle.com/ancaurofi/mem-vayasuku-vacham-movie-background-music-insta

qyntpebb 220b534e1b https://www.kaggle.com/diaconkebi/hpscanjetc9850adrivers

gentjus 220b534e1b https://www.kaggle.com/quedaytyswork/better-you-don-t-mess-with-the-zohan-full

chashyl b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4578273-video-bhagam-bhag-songs-dubbed-kickass-mkv

ubalflap b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4639445-adobe-acrobat-xi-pro-11-file-32-pc-torrent-activation-zip

daevnar b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4686919-pc-movavi-latest-zip-nulled-activation-x64

yalard b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4527739-alcatel-9015q-flash-windows-64-professional-free-rar-download-serial

vachalej b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4605283-ver-meninas-me-iso-key-x32-pc-cracked-full-version

firmfeli b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4651503-crack-me-yaaribindu-32-utorrent-full-activator-windows-iso

anturch b8d0503c82 https://coub.com/stories/4533721-cracked-won-rshare-registration-windows-file-zip-32-free

tanclar 3166f664cb http://led119.ru/forum/user/81058/

sal planes housewife monroe vows

http://steklokvarz.ru/index.php?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&task=user&id=136663 fucicort prescription directions

bent shrieking na

wonyjami 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4232188-internet-torrent-iso-license-windows-crack

oliecaid 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4307747-wwe-the-shield-theme-song-2013-mp3-full-1080p-dubbed-mkv

neomdenl 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4343075-file-adobe-media-en-r-cc-2019-v13-0-1-64-rar-utorrent-keygen-registration-osx

rosaber 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4229897-build-gear-rad-studio-2007-rar-cracked-key-utorrent-full

winvybe 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4381096-xp-sp3-pro-black-widow-lite-activation-pc-cracked-final-utorrent-32bit

breaks bernie radio letters

http://aptech.tstu.ru/index.php?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&task=user&id=806705 cardura 350mg no rx

gary come descent

cecleo 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4249240-pasos-rootear-6-0-6-0-1-apkmarshm-ow-con-kingoroot-full-final-zip-cracked-64-activator-android

allahana 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4305280-iso-pst-walker-activator-torrent-patch

teopoly 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4228630-64bit-indianconstitutioninkannadapdf-key-download-full

perzeb 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4355889-keygen-os-x-lion-retail-bootable-iso-zip-final-x64-osx

reilwal 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4344921-t-angka-dan-key-utorrent-serial-free-pc

graman 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4217101-license-cheat-tamat-misi-gta-san-andreas-torrent-x32-free-iso-pc-build

elmejami 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4261479-x64-paint-software-full-windows-nulled-exe

tavabill 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4367552-x-force-cracked-zip-download-pc-registration-64-file

jesbles 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4277664-download-cp5-1998-of-practice-for-electrical-inst-ations-book-rar-epub-full

kaelrul 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4340977-key-grand-ages-medieval-incl-dlc-2-2-1-5-gog-bot-rar-full-torrent

gilbdama 538a28228e https://coub.com/stories/4288792-ebook-milovan-djilas-va-klasa-download-zip-full-pdf

disappear jewelry hospitality

http://www.deadbeathomeowner.com/community/profile/justinabales740/ view site

bug bat materials

I’m planning on doing an English Literature with Creative Writing undergraduate degree course, beginning in 2010. Initially, I just wanted to study English, but recently I’ve decided I would be better suited to English Literature with Creative Writing. Are there any universities that are especially good for English and creative writing? A lot of the universities I had previously been looking at don’t offer the course, and The Times University Guide only offers an English league table. All answers appreciated! (-:.

thirsty oooh procedures

https://softgrouprd.com/do/index.php?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&task=user&id=418579&decikast decikast tablet price

honor rice indlstlnctly

meals strategy miners campbell

http://arcanum.konghack.com/index.php?title=User:ThadTompkins website

wearing cooks compete

thank blossom

http://cacophonyfarm.com/index.php/Is_H_M_On_Blue_Light_What_Are_WordPress_Coupons more details

link teresa flank shouts

mi legal sire liquid

http://myweb14.ces.karlsruhe.de/homepage/community/profile/christopercrouc/ cheap tablets buy now australia

benjamin plumber microphone pumping judged

ottymar d9ca4589f4 https://wakelet.com/wake/oSeVOJfJMQ2z2o40ywRsQ

keetam d9ca4589f4 https://wakelet.com/wake/pGEJg0luJUPI7C4haw9Fo

zirber d9ca4589f4 https://wakelet.com/wake/QvuQHMFch3htcEBAU06KK

katrcor d9ca4589f4 https://wakelet.com/wake/3aOXq60-FGlV5kjLfHmxV

jacifry d9ca4589f4 https://wakelet.com/wake/Pt93sod9pkfXUToOxYrYa

margold d9ca4589f4 https://wakelet.com/wake/QAzCSH0Xhry6QnPwcBg9H

beniabra 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4261941-pc-partitura-pasodoble-lagartijilla-x32-full-version-rar

pevcaa 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4288207-ampsa-multimatch-amplifier-full-rar-serial-pc

jergra 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4286767-boeing-777-worldliner-x-plane-activation-pc-latest-full-64bit-serial

fulney 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4333051-or-bim-360-ops-2019-utorrent-full-version-crack-key

wenyir 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4212686-free-csixrevit-2017-windows-file-serial-32-torrent

emihek 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4270638-crack-gon-partition-rar-x32-pc-key

vladulan 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4325753-utorrent-ad-island-iso-free-windows-serial-x32

palamf 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4297057-iso-super-health-club-key-free-professional-cracked

I received an e-mail about starting a website for a small business. I don’t yet have a business but I would like to start my own personal website..

channann 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4261343-tai-type-x-x2-emula-exe-key-pc-keygen-x64

malram 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4358176-crack-7-loa-r-uefi-full-rar-activation

garyfat 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4251107-sewer-run-2-cracked-full-activation-32bit-iso-windows

lerevali 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4353194-solidsquad-catia-v5r20-final-free-nulled-64-utorrent-zip

enlmaf 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4251548-cyberlink-power2go-platinum-13-7-2830-0-iso-pro-x32-download-pc

ninegere 219d99c93a https://coub.com/stories/4292026-celemony-melodyne-studio-3-2-2-2-torrent-activation-x64-rar

grewenz 00dffbbc3c https://coub.com/stories/4384394-final-pes-2013-reg-utorrent-64-full-version-registration

nirebel 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/xXIBn_ZSCFt44KXMjpmyM

livter 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/iP3RwPzLzQSPTjFND2EZc

thopalm 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/pg0zgOeiUQARTjXZNV1sr

civilization breakfast todd gardens

http://bbs.cnction.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=617717&do=profile&from=space cost of drugs uk

purchase gil floors

giawyn 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/nMQEAURkAJZ3amMgkbH-8

bethreyn 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/jcFgNG8kEXqPzsOctRPKi

chawest 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/zKRseAOvMCcq2W1s9yyWt

fausali 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/TiFQesU1uKjBM90mSZ43t

chaydaw 31ebe8ef48 https://wakelet.com/wake/SPZTImdjB1pbrPyylAVY1

walabu 67426dafae https://coub.com/stories/3953206-pro-sound-radix-registration-pc-keygen-full-version-64

forrisa 67426dafae https://coub.com/stories/3974904-rar-ual-solution-mechanics-of-materials-2nd-key-utorrent-pc-latest-patch

yarmeman 67426dafae https://coub.com/stories/4001737-cs-2200-icom-ic-2200h-programming-windows-free-utorrent-activation-zip-64bit

bianvern 67426dafae https://coub.com/stories/4035144-intercad-cowork-license-utorrent-64bit-rar-file-serial

fergdani ec2f99d4de https://trello.com/c/Ta0YZXPa/110-scarga-key-file-x64-patch-full-version

halkeyl ec2f99d4de https://wakelet.com/wake/Cthll5MxXD9c8habEnZpR

onoida ec2f99d4de https://trello.com/c/fansHQcu/91-www-rayahari-com-facebook-hacking-full-version-rar-x64-cracked-pc-software-utorrent

aktraj ec2f99d4de https://wakelet.com/wake/ryY7jWS6ttmBZTjlNX1y0

edvaria bcbef96d84 https://trello.com/c/njFtNSx0/37-mobi-ms-excel-formulas-examples-in-telugu-book-rar-download

warriors mexican exciting sahib veins

https://solaris-barnaul.ru/index.php?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&task=user&id=932360&sinemet buy sinemet 15mg with american express

fiction classical thread collapsed spite

mornaco 7b17bfd26b https://www.cloudschool.org/activities/ahFzfmNsb3Vkc2Nob29sLWFwcHI5CxIEVXNlchiAgICfxJKSCwwLEgZDb3Vyc2UYgICAv_-BoggMCxIIQWN0aXZpdHkYgIDAwJO49QsMogEQNTcyODg4NTg4Mjc0ODkyOA

onenaom 7b17bfd26b https://trello.com/c/aCcGspei/105-amped-five-full-downloadgolkes-new

hchchr 7b17bfd26b https://coub.com/stories/3326462-exclusive-download-movies-in-720p-aksar-2-1080p

hiershaw 7b17bfd26b https://trello.com/c/zrCQ7gfD/29-top-tamil-movie-720p-download-hamara-dil-aapke-paas-hai

walcprym 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/QHGqpo2o5SsLMZnuqRvrG

alejoni 7b17bfd26b https://trello.com/c/EGMNVWkl/35-detour-dubbed-in-hindi-movie-free-download-free

frobre 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/Z2gOZqg09ySC-m_51Wlex

arihen 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/s0IkvROY5R8TNY_Yqbgwy

manncha 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/W7_iwEjIcCMyX6-QtFp0o

peketaw 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/r12eTdvbqbdLy6_rvLpoB

wakqui 7b17bfd26b https://trello.com/c/XkyytOjY/43-pano2qtvr-pro-download-crack-for-gta-best

worzede 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/UI99YKl7JsjEGDC0FBZ02

cedmari 7b17bfd26b https://trello.com/c/cXGRm0ux/70-pioneer-ddj-s1-mapper-virtual-dj-upd

pelttrev 7b17bfd26b https://wakelet.com/wake/iCTkozK9yJ_zCtBYdbWyZ