And who by brave assent, who by accident, who in solitude, who in this mirror, who by his lady’s command, who by his own hand, who in mortal chains, who in power, and who shall I say is calling? -Leonard Cohen

And who by brave assent, who by accident, who in solitude, who in this mirror, who by his lady’s command, who by his own hand, who in mortal chains, who in power, and who shall I say is calling? -Leonard Cohen

One of the most notable trends in the realm of spiritual life across the globe in recent decades has been unprecedented growth in the area of mysticism and magic, in particular the movement generally referred to as the “New Age.” Generally, the “New Age” refers to a complex of spiritual and “consciousness-raising” movements, originating in the 1980s but with roots in the 1960s and 1970s, and covering a range of themes, from spiritualism and reincarnation to holistic approaches to health and ecology. Not all spirituality is New Age, and not all of the New Age is spirituality, but the core notion of the movement is that a spiritual era is dawning in which individuals and society will be transformed.

In Israel, the New Age manifests wide diversity and influence, and can be understood as a new religious stream in Israeli society, crossing traditional boundaries which have typically divided the country between either “religious” or “secular” camps. Israel, in a manner disproportionate to its population, is a major importer and exporter of the New Age. Every year scores of New Age teachers offer widely attended seminars in alternative medicine, healing, and mystical and magical practice. Publishers specializing in New Age topics have translated hundreds of books. In addition, Israel is a leader in the export of mysticism and magic. Israelis and former Israelis teach in both East and West, and practices originating in Israel, such as the system of Avi Greenberg or the Feldenkrais Method,® have garnered major followings outside of Israel. As both “import” and “export,” the phenomenon of the New Age can be understood as an important element in Israel’s globalization – we can no longer comprehend new phenomena in Israel without relating them to developments in the world as a whole – a social and cultural shift that in and of itself has a tremendous impact upon Israel today.

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, Torah and Kabbalah have come to play a key role in the New Age. On the one hand, Kabbalistic groups, most prominent among them followers of Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag (1885-1954), the author of the “Sulam” commentary on the Zohar, have absorbed values and practices from general cultures of mysticism; on the other hand, these schools have spread Kabbalistic teachings to an unprecedented degree, ultimately creating an international Kabbalistic movement, the Kabbalah Centre International, that has devotees far beyond the confines of Jewish world, the most famous example being, of course, Madonna.

It is possible to point to several types of criticism against contemporary mysticism. Rationalists both religious and secular – the most famous amongst them being Yeshayahu Leibovich – reject all forms of mysticism and magic, and follow the growth of any movement employing them with anxiety. I do not participate in this criticism, as I see in both mysticism and rationalism viable expressions of the cultural and psychological richness of the human experience. In my opinion, mysticism is an authentic vehicle for the pursuit of wonder and the ineffable of which poets and artists also partake. But as one who usually sees mysticism in a positive light, I am also willing to criticize certain of its popular expressions. One form of this criticism is “internal,” and I base it on the long legacy of cautions and concerns amongst traditional mystics themselves, and the second is “external,” based upon contemporary concerns regarding power.

First the “internal” critique. Traditional mystics have long criticized mysticism that focuses on subjective experiences such as ecstasy as ends in themselves, at times even describing these experiences as a wrong turn on the mystical path. St. John of the Cross (16th century Spain) wrote that mystics must learn to part from ecstatic experiences just as an infant must be weaned from nursing from its mothers’ breasts. For St. John of the Cross, ecstasy is an immature, passing expression of the mystical life. Similarly, in criticizing the Sufi ecstatic dancers – who have emerged to enjoy widespread popularity in our day – the great Muslim Sufi mystic Muhyiddin Ibn al-Arabi (12th-13th centuries) condemned their shift from serious mystical practice to what he considered to be “frivolousness.” Even the Kabbalah of Abraham Abulafia, the most focused on mystical experience, is interested in experience not for its own sake but for the purpose of receiving prophecy. Those who engage in New Age spirituality for the purpose of “getting high” are, according to such figures, missing the point.

First the “internal” critique. Traditional mystics have long criticized mysticism that focuses on subjective experiences such as ecstasy as ends in themselves, at times even describing these experiences as a wrong turn on the mystical path. St. John of the Cross (16th century Spain) wrote that mystics must learn to part from ecstatic experiences just as an infant must be weaned from nursing from its mothers’ breasts. For St. John of the Cross, ecstasy is an immature, passing expression of the mystical life. Similarly, in criticizing the Sufi ecstatic dancers – who have emerged to enjoy widespread popularity in our day – the great Muslim Sufi mystic Muhyiddin Ibn al-Arabi (12th-13th centuries) condemned their shift from serious mystical practice to what he considered to be “frivolousness.” Even the Kabbalah of Abraham Abulafia, the most focused on mystical experience, is interested in experience not for its own sake but for the purpose of receiving prophecy. Those who engage in New Age spirituality for the purpose of “getting high” are, according to such figures, missing the point.

In addition, mystics of many religious traditions have rejected the use of mystical practices for the sake of personal material gain. In the Jewish world, Kabbalists traditionally emphasized practices intended for serving the needs of the divine realm, and not simple human needs such as personal advancement. According to Rabbi Meir ben Ezekiel Ibn Gabbai, amongst the great Kabbalists of the 16th century, a person mixing intentions of personal gain with mystical practice is akin to one who “brings uncleanness into the Temple and profanes the Holy of Holies.” (Avodat HaKodesh 2, 6) Even those Kabbalists such as Rabbi Hayyim Vital – the major disciple of the “Ari” (Rabbi Yitzhak Luria) – who were more tolerant of those seeking personal gain emphasized that the Kabbalist should receive “his portion only at the end” (Shaarei Kedusha 3, 8). Traditional mainstream Kabbalistic traditions hold that one of the main goals of Kabbalah is human responsibility for serving the divine realm through mystical practice. Kabbalists affiliated with these traditional streams note time and time again that the Kabbalistic path is securely aligned with divine service though fulfillment of commandments and perfection of personal conduct. Rabbi Hayyim Vital, for example, lists complete obligation for the commandments and intensive examination of personal conduct as preconditions for any valid experience of prophecy via mystical practice (Shaarei Kedusha 3, 3). Kabbalistic literature teaches students a variety of internal, personal limits for controlling the study and use of esoteric knowledge in addition to well-known external restrictions such as age, Torah knowledge, and family status. And yet as is well known, the Kabbalah Centre and others regularly promise all variety of personal and financial gain to adherents, also stating that the benefits of Kabbalah are available to all.

A second form of my criticism of New Age phenomena comes not from within Kabbalistic and other mystical sources, but from more contemporary concerns: in particular, on issues of “power,” an essential element in contemporary mystical manifestations and a very useful tool for tracking the key changes that have taken place in classical mysticism as it has evolved into contemporary mystical forms.

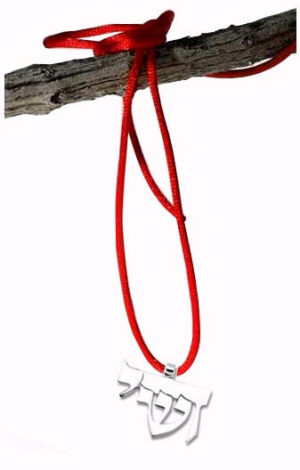

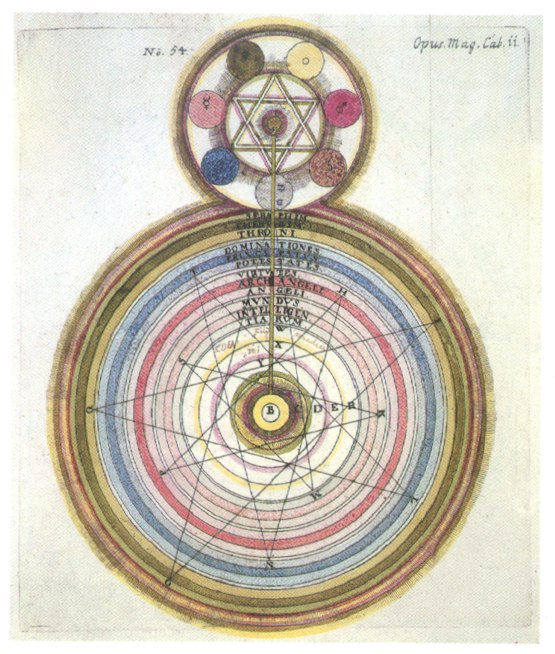

Many classical Kabbalistic writings explore Jewish mystical perceptions of “personal power” in the form of a leader who can be a “chosen one” or “tzaddik” for the community. Some Jewish groups such as the Hasidism forge these teachings into fixed social structures. However, it is very clear that this personal power was meant to be integrated into other forms of power – the power of the sefirot, holy places, Hebrew language, Torah, and so on. Furthermore, as noted above, focus on personal power was ultimately linked to serving the needs of the power of the upper realms. In contrast, in some forms of contemporary Kabbalah, personal power is an end unto itself, while traditional loci of power, such as the Torah and others, decrease in importance. (Ironically, despite the rhetoric of self-empowerment, in practice students are made extremely passive before powerful authority figures.) It is easy to identify the deep differences in traditional and contemporary approaches to personal power by comparing a text such Nefesh Hahayyim by Rabbi Hayyim of Volozhin – a major student of the Gaon of Vilna in the 19th century – which is essentially a song of praise for the sacrifice of the individual dissolving personal desires for the good of the power of the Torah – to contemporary Kabbalistic writings that describe the personal power and personal gain one can obtain by studying Kabbalah. Note, for example, the title of a “pop Kabbalah” book by Yehudah Berg, a follower of the school of Rabbi Ashlag and director of the Kabbalah Centre: The Red String Book: The Power of Protection (Technology for the Soul). Emphasis on “personal power” is a part of the fusion of these schools of contemporary Kabbalah with the New Age, a blurring of the core Jewish elements of Kabbalah.

====

It is reasonable to posit that the very same trends of shifting notions of power in Kabbalah in the 20th century have led important Kabbalistic streams – particularly those derived from the school of Rav Kook, emphasizing the unique power of the Jewish nation – to fuel the dramatic rise in “mystical Jewish nationalism.” Looking carefully at the development of the school of Rav Kook reveals phenomena of the “privatization of power” very similar to the search for “personal power” noted above.

For example, members of the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva (founded by Rav Kook) have followed Rabbi Tzvi Yisrael Tau of the Har HaMor Yeshiva in splitting with the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva in protest against its becoming too academic, and, as noted by researcher Dov Schwartz, have moved towards focusing on highly individualized internal spiritual practices, the nurturing of “chosen ones,” and rejection of all forms of social, political, and “external” activism. Such streams tend to break with the mainstream modes of living and public life in Israel. These tendencies have recently increased in the aftermath of the “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip. Many of the followers of Rav Kook today, occupied as they are with his previously censored notebooks, emphasize the very personal layers of his writing – material that was shunned in the early period of the development of the school of Rav Kook. These poetic texts, now garnering much attention in certain circles, call for freedom from societal and even halakhic restraints in order to fulfill the goal of personal fulfillment. An additional contemporary expression of the “privatization of power” is the phenomenon of the “Hilltop Youth” [Groups of teenagers and other young people engaged in provocative, and at times illegal, right-wing political action in Gaza and the West Bank – Ed.] whose values at times overlap with tenants of the New Age – personal empowerment leading to anarchic and individualistic modes of behavior while attacking perceived political and religious burdens. In some ways, the “Youth of the Hilltops” represent a more extreme version of the “Jewish Underground” of the 1980s, who promoted autonomous expressions of power against the Israeli government.

For example, members of the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva (founded by Rav Kook) have followed Rabbi Tzvi Yisrael Tau of the Har HaMor Yeshiva in splitting with the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva in protest against its becoming too academic, and, as noted by researcher Dov Schwartz, have moved towards focusing on highly individualized internal spiritual practices, the nurturing of “chosen ones,” and rejection of all forms of social, political, and “external” activism. Such streams tend to break with the mainstream modes of living and public life in Israel. These tendencies have recently increased in the aftermath of the “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip. Many of the followers of Rav Kook today, occupied as they are with his previously censored notebooks, emphasize the very personal layers of his writing – material that was shunned in the early period of the development of the school of Rav Kook. These poetic texts, now garnering much attention in certain circles, call for freedom from societal and even halakhic restraints in order to fulfill the goal of personal fulfillment. An additional contemporary expression of the “privatization of power” is the phenomenon of the “Hilltop Youth” [Groups of teenagers and other young people engaged in provocative, and at times illegal, right-wing political action in Gaza and the West Bank – Ed.] whose values at times overlap with tenants of the New Age – personal empowerment leading to anarchic and individualistic modes of behavior while attacking perceived political and religious burdens. In some ways, the “Youth of the Hilltops” represent a more extreme version of the “Jewish Underground” of the 1980s, who promoted autonomous expressions of power against the Israeli government.

At the same time as “power” is increasingly sold as a New Age product, it is ironically disempowering in political terms. The intersection in the rise of the personal model of power in Kabbalah and New Age values of “self empowerment” in recent decades is expressed by a variety of forms of abandonment of mainstream Israeli society. The belief that “peace begins within” can, in some expressions of it, lead to an exclusive focus on internal, individualistic harmony, as opposed to a sense of public responsibility for social or political change. It is precisely because the emphasis on personal power and fulfillment in the New Age blends so seamlessly with the ideologies of late capitalism that I have chosen to describe New Age teachings about individual power as “privatization of power.” Privatization of power on an individual level goes hand in hand with the abuse of the movement by commercial marketing of products designed to facilitate access to power by spiritual seekers. The New Age movement has become a major industry with a wide variety of products – festivals, books, cosmetics, medicines, seminars, and more.

In the vocabulary of the New Age, “mysticism” is not only a product, it is a label. In a world where the acquisition of knowledge has definite class mobility and economic value, individuals continually seek avenues for quick access to wisdom or knowledge that results in both recognition and material gain. Within the New Age movement, economic class often determines who is exposed to the highest-value mystical products. People who can afford to travel abroad or are able to purchase expensive items can expect better results in their quest while members of the lower classes must make do with products of lesser value. It is ironic that certain followers of Rabbi Ashlag, a Kabbalist whose teachings edged closer to socialism than those of his contemporaries, are purveyors of expensive products marketed to their most well-off students. Rabbi Ashlag’s altruistic, psychological premise of “desire to influence” has mutated into a gospel of an egoistic “desire to receive.”

In the vocabulary of the New Age, “mysticism” is not only a product, it is a label. In a world where the acquisition of knowledge has definite class mobility and economic value, individuals continually seek avenues for quick access to wisdom or knowledge that results in both recognition and material gain. Within the New Age movement, economic class often determines who is exposed to the highest-value mystical products. People who can afford to travel abroad or are able to purchase expensive items can expect better results in their quest while members of the lower classes must make do with products of lesser value. It is ironic that certain followers of Rabbi Ashlag, a Kabbalist whose teachings edged closer to socialism than those of his contemporaries, are purveyors of expensive products marketed to their most well-off students. Rabbi Ashlag’s altruistic, psychological premise of “desire to influence” has mutated into a gospel of an egoistic “desire to receive.”

Here we come to full expressions of “external” criticism against the social and economic interests espoused within the rise of contemporary mysticism, as the selling of mysticism becomes part of a global political movement linking the worlds of spirituality and economic power. Social critic Ivan Illich, author of Deschooling Society, a religiously conscious critique of modern society, describes the contemporary Western individual as a “homo economicus” – an economic being – who experiences all reality through terms of prosperity or need. With this critique in mind, it is not surprising to find that the culture of the New Age in our day favors “short cuts” speeding up the long and at times turbulent path towards mystical knowledge and individual perfection with of a range of purchasable miracle cures, offering personal power through magical objects (crystals, holy water, etc.). Or consider the repetition of mantras and sayings, affirmations with the power to change reality. Traditionally, magic was performed by use of “whispering” as part of larger faith systems about holy language – for example Hebrew in Jewish traditions and Arabic in Muslim ones. In New Age practice, linguistic models focus on the search for “magic words” taken completely out of their original cultural-religious contexts. For some of Rabbi Ashlag’s followers, traditional Hebrew phrases for the “Name of God” are removed from traditional usages and employed for the sake of gaining power. Consider other “short cuts” such as advanced seminars in which students are given the title “master” in return for a large fee.

In the Jewish context, the rise in the power of the tzaddik equates with a decrease in the power of the halakha (Jewish law) as a system capable of creating meaning in the realm of New Age. In the eyes of many New Age seekers, the power of the chosen one stands above the power of the halakha – a trend obvious in the writings of the New Age but perhaps less obvious in the writings of halakhic figures such as Rabbi Yitzhak Ginsburg. Ginsburg, a Chabadnik, is a spiritual authority for many in the settler movement. Amongst other works he has written Baruch HaGever (“Blessed Is the Man”), praising Baruch Goldstein, a Jew who murdered over thirty Muslims in a mosque on Purim 1994. As with the similarity between the Kabbalah Centre’s emphasis on “personal power” and some followers of Rav Kook, non-traditional and traditional contemporary figures often make use of very similar themes.

Despite much social criticism, there are more optimistic views of concerning the New Age.” Social theorist Phillip Wexler sees new streams of social activism and organization embedded in the wave of contemporary mysticism, allowing spiritual language and values to enter the public sphere. In the Jewish context we can note Rav Shagar, leader of the Siach Yitzhak Yeshiva, a center of inspiration for the national religious movement. In his book Broken Vessels Shagar looks approvingly towards the New Age as an opening for spiritual renewal in the Jewish world.

In my own criticism of the New Age, I do not intend to offer a blanket condemnation. It is clear that the revival of mysticism in our days has allowed for the release of many talents and trends pushed aside or ignored in the past. The New Age has also prodded forward the public presence and growth of mystical traditions that were once thought to be merely tangential to general religious culture. (Scholars especially benefit from this!) Still, the rise in mysticism amidst globalization threatens to blur the unique elements of different mystical paths as they become products in the spiritual supermarket. So, for example, in bookstores the works of the great mystical teachers of the past are being pushed aside in order to promote magical objects and self-help guides claiming to teach speedy paths to personal power. In this sense, a trend that was hoped to enrich cultural dialogue actually serves powers promoting commoditization of any content potentially saleable in systems that already distribute material wealth unequally.

Furthermore, the profound nature of the mystical experience, in my opinion, obligates us to protect it from superficiality and the marketplace. As such, the “internal” criticism of New Age promotion and marketing of mystical content is actually more crucial than the “external” criticism of its privatization of power. One the major proponents of Buddhism in the West, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, criticized the idea of “spiritual materialism,” a term he used to describe the less obvious ways that spirituality is used for material gain or raising status. His implication was that the use of heightened spirituality to increase the power of the ego and identity conflicts directly with practices meant to decrease the impact of such limiting components, blocking the seeker’s openness to unknown mysteries which are the ultimate goal of the mystical path. When the New Age does not sin in the ways of sheer materialism, it more often than not tends toward spiritual materialism in the way that Trungpa implied. As we conclude, it is worth considering the words of Trungpa concerning “sadhana,” the preparations for the meditative practice mahamudra, an advanced form of meditation found in Tantric Buddhism: “If we make use of dharma [the Buddhist path] for personal gain, then the river of materialism will rise above us. When materialism takes control, the consciousness is drunk with the follies of the world.”

I was recommended this blog by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my problem. You’re incredible! Thanks!

if you want to hire some good wedding singers, always look for a singer with a background in classical music,

Many thanks for making the effort to discuss this, I feel strongly about this and enjoy studying a great deal more on this matter. If possible, as you gain expertise, would you mind updating your webpage with a great deal more details? It’s extremely beneficial for me.

I am glad to be one of several visitants on this great web site (:, regards for posting .

Hey! This post couldn’t always be written much better! Examining this post reminds me of these area mate! He always stored talking about this. I’ll ahead this article to be able to your ex. Convinced he will have a very good go through. We appreciate you revealing!