This past Sunday in a rented storefront in Crown Heights, Vaybertaytsh, a podcast which producer Sandy Fox bills as “the first—as far as we know— Yiddish speaking, feminist radio program” celebrated the release of its second season.

Before it was a podcast, “Vaybertaytsh” – literally “translations for women” in Yiddish—was a term once used for commentaries on Torah written by Hebrew-literate Ashkenazi men for their Yiddish-speaking women wives (and other women) who were unlikely to learn the “Loshnkoydesh” (“holy tongue”) themselves. “Vaybertaytsh” also came at times to refer to the language of Yiddish itself, one of many names the “jargon” (another slang term for Yiddish) went by.

This podcast is a project of reclamation of the word. Women themselves become the teachers, “flipping the concept of ‘vaybertaytsh’ on its head,” says Fox, “explaining and commenting on our own terms.” Interviews in the first season included a midwife serving the Hasidic community, a female cantor for the renewal movement in Germany, and several international attendees of the Women’s March last January.

These interviews and conversations take place entirely in Yiddish, and the podcast draws guests mainly from the international community of Yiddishists, a group which speaks Yiddish in order to preserve the language. The Yiddishist movement began at the turn of the 20th century as activists and scholars sought to “legitimize” what was at the time seen as a “low” tongue, spoken by unsophisticated people—and women. “Those scholars were primarily men whose mission was to de-feminize Yiddish, to distance the language from its association with women as a ‘mameloshn,’ [or ‘mom’s tongue’],” Fox told me.

Sandy Fox, who also goes by the Yiddish name Sosye, describes Vaybertaytsh both as a continuation and a refutation of that philosophy. Just as these men sought to produce mainstream literature and journalism in Yiddish, Fox creates episodes of Vaybertaytsh available for download on any podcast app.

But unlike this earlier wave of Yiddishists, Fox does not shy from association with women or the home. The pilot opens with a tribute to the Riot Grrrl music movement , and another episode in the first season is devoted to a conversation between women who have lost their mothers on their memories of those women.

Nor does Fox insist on a rigid grammatical purity, as the first wave of many turn-of-the-century Yiddishists did. “I don’t really believe there is such a thing as ‘authentic’ Yiddish,” she says, “and it can be uncomfortable to speak perfect clinical Yiddish.” Vaybertaytsh’s opening episode contains a kind of non-apology for any grammatical “mistakes” the podcast may make: “Let’s simply feel free to speak” says Fox in the first episode (in of course, Yiddish). Creating something new is “too important to wait for a perfect Yiddish.”

As a Yiddish learner who speaks with less than perfect grammar, this stance excites me. More than once I have lost my train of thought while speaking due to interruptions correcting my grammar. While such interruptions are kindly meant and an important part of the language-learning process, they can make communication a little exhausting. “Often it’s been men serving as the gatekeepers,” Fox notes. That gate-keeping can turn people away from actually speaking the language, something the relatively small community of Yiddishists arguably cannot afford.

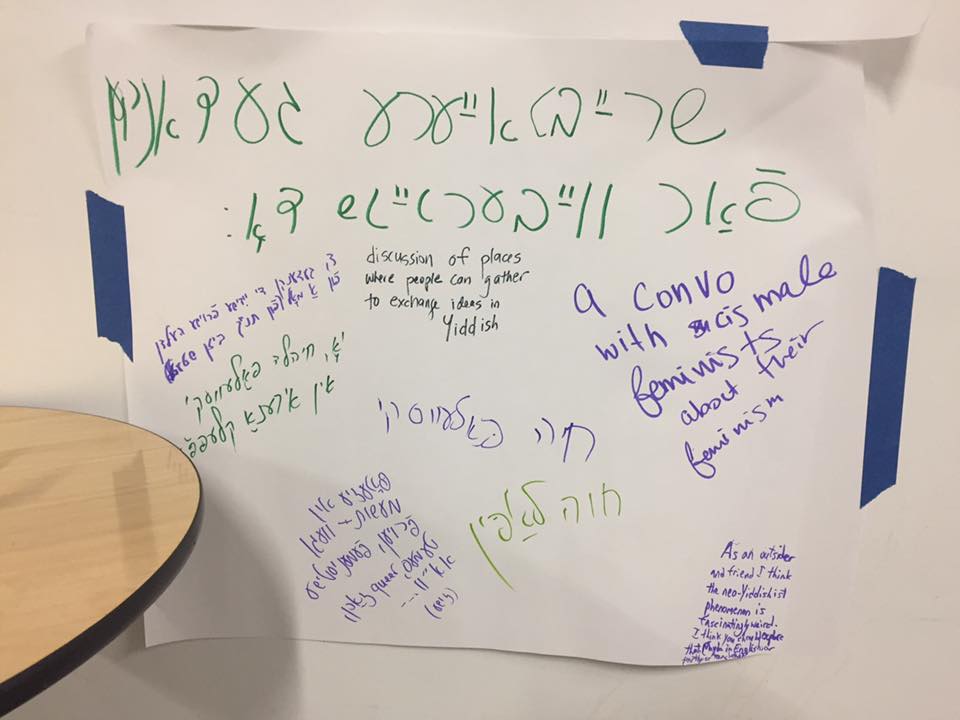

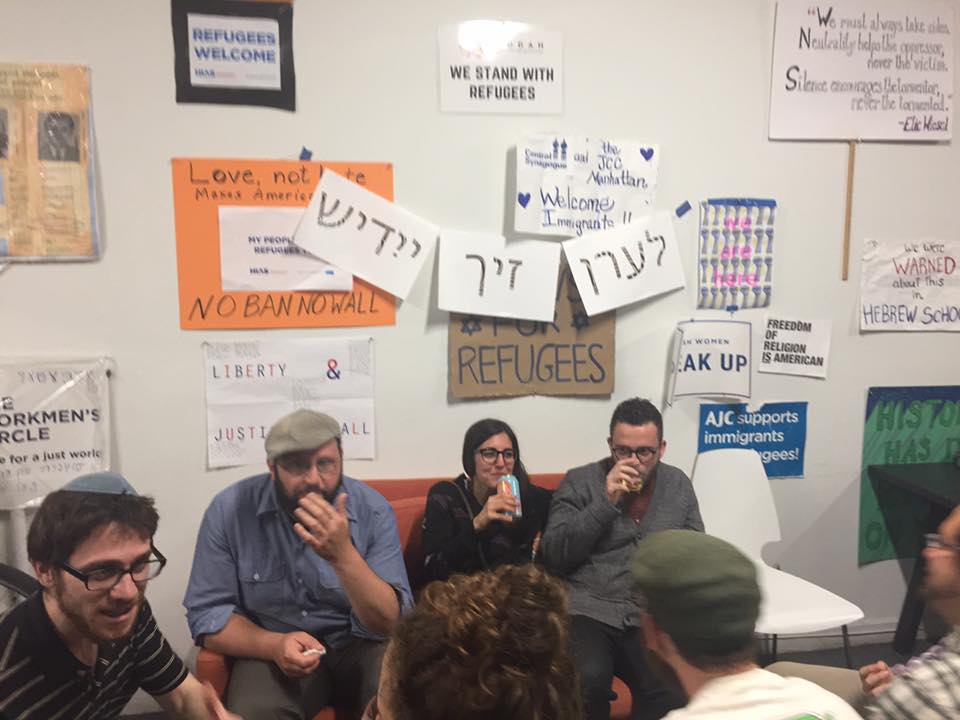

At the second season’s release party, Fox welcomed non-Yiddish-fluent guests to “Yiddishland” before continuing entirely in Yiddish, while translations in English appeared onscreen behind her. “Maybe it seems weird, considering the fact that we all speak English. But such is the way of the Yiddishists,” the screen read, “Welcome to our world.”

The default language of the night was Yiddish, with a “learner’s couch” equipped with a dictionary. Party attendees schmoozed over the food, the drinks, and the choice of women’s social justice groups to which to donate the nights proceeds (the winner was Days for Girls), all in Yiddish of varying fluency. Emboldened by the podcast’s premise, I took my time forming clunky sentences for concepts that I might have communicated much faster in English. By the time the event ended, I was only rarely asking my conversational partners to repeat themselves.

One man asked me near the evening’s end how I had first encountered Vaybertaytsh. I told him I’d heard of it online, I’d been unsure if my language comprehension would be strong enough to follow along, but I eventually checked it out and was using it to train my ear. “And here I am!” I finished exuberantly. My conversational partner nodded. “Okay. But I didn’t mean the podcast—I meant the language.”

Rachel Wetter is an educator and history nerd living in New York who also goes by Rokhl.

Images via Facebook.