While Alice is Through the Looking Glass she argues with Humpty Dumpty over his use of the word “glory” to denote not the usual meanings of the word but “a nice knock-down argument.” He responds scornfully: “When I use a word… it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.” Their debate cuts to the heart of language: if a word does not have an agrdeeed-upon definition, but has only a subjective, idiosyncratic, and contingent intention behind it, then it fails to convey anything other than a set of arbitrary phonemes. It is not a word, but a sound.

While Alice is Through the Looking Glass she argues with Humpty Dumpty over his use of the word “glory” to denote not the usual meanings of the word but “a nice knock-down argument.” He responds scornfully: “When I use a word… it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.” Their debate cuts to the heart of language: if a word does not have an agrdeeed-upon definition, but has only a subjective, idiosyncratic, and contingent intention behind it, then it fails to convey anything other than a set of arbitrary phonemes. It is not a word, but a sound.

Unlike Humpty’s definition of “glory,” the definition of terrorism is no abstract semantic problem but a pressing and fundamental question. Five years on from the atrocities of 9/11, no single issue is as vital, occupies as much global attention or has such a hold on the global purse as ‘terrorism.’ It is the cause, ostensibly, of the present wars and occupations in the Middle East. It has provoked the spending of hundreds of billions of counter-terrorism dollars. And it has spawned obsessive, continuous coverage of the subject on the internet, the broadcast media, and by Hollywood. But no one, including the experts, knows exactly what it is. We are left like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart who, faced with the task of defining obscenity, felt he “could never succeed in intelligibly doing so,” and so preferred to simply say, “I know it when I see it.”

Yet how we define ‘terrorism’ determines how we identify it, how we best counter it, and how we define the limits of what our societies find acceptable. In this article, I will first explore the linguistic meanings of the term “terrorism,” identifying two distinct strands, or chains, of the terrorist episode: the act (or threat of action) by one party against another, and, secondly, the way that act is covered, communicated, and by being communicated, fulfilled. And I will conclude by exploring how our failure to define terrorism exculpates ourselves and perpetuates the cycle of violence we seek to fight.

1. The Medium is the Message: All Language is Political

The term “terror” in its modern political sense was initially used by Robespierre as a badge of pride for his purging of the regressive monarchic elements of revolutionary France. “Terror, he said, “is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore an emanation of virtue; it is not so much a special principle as it is a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to our country’s most urgent needs.” (See Robespierre’s “On the Moral and Political Principles of Domestic Policy,” online at www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/robespierre-terror.html) Yet the term was quickly taken up as a term of abuse by, among others, Edmund Burke (see the San Francisco Chronicle for a brief history). In other words, from its beginning the meaning of the word “terror” has been contentious.

Today, there is no single accepted definition of the term, despite literally hundreds of definitions of ‘terrorism’ online, including several ones from different branches of the world’s primary counter-terrorist agent, the U.S. government. The debate over its definition is so clearly an aspect of the phenomenon of terrorism that Wikipedia even carries an entry for the “Definition of terrorism” separately from its entry on ‘terrorism.’ The entry states that “The definition of terrorism is inherently controversial” and notes, with self-justifying glee, that “ ‘Terrorism’ has never been defined…” (36 Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 2&3, 2004, p. 305)

Clearly there are some commonalities among the definitions — violence, fear, intention to affect groups for ideological reasons – but different groups stress different aspects. The FBI stresses the criminal violence of terrorism in its description of terrorism as “the unlawful use of force or violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” (emphasis added) Note that the FBI’s definition does not mention the deliberate targeting of civilians, just the intimidation of them. Nor does it, presumably, mean “unlawful” in the sense of international law, since by that standard the U.S. incursion into Iraq and most of Israel’s military actions in the West Bank would constitute terrorism. The Department of Defense’s definition similarly stresses the unlawful nature of the violence and the intentionality of the terrorists and their targets, defining terrorism as “the calculated use of unlawful violence or threat of unlawful violence to inculcate fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate governments or societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological.”

Clearly there are some commonalities among the definitions — violence, fear, intention to affect groups for ideological reasons – but different groups stress different aspects. The FBI stresses the criminal violence of terrorism in its description of terrorism as “the unlawful use of force or violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” (emphasis added) Note that the FBI’s definition does not mention the deliberate targeting of civilians, just the intimidation of them. Nor does it, presumably, mean “unlawful” in the sense of international law, since by that standard the U.S. incursion into Iraq and most of Israel’s military actions in the West Bank would constitute terrorism. The Department of Defense’s definition similarly stresses the unlawful nature of the violence and the intentionality of the terrorists and their targets, defining terrorism as “the calculated use of unlawful violence or threat of unlawful violence to inculcate fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate governments or societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological.”

The Department of State, in contrast, specifies the type of actor and defines terrorism as “premeditated politically-motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatant targets by sub-national groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience.” The United Nations — often useful for providing an unratified conclusion — here only notes a few of the alternatives that might be agreed upon, assuming that a consensus could indeed be agreed upon. (See http://www.unodc.org/unodc/terrorism_definitions.html).

The UNDOC attempt to define ‘terrorism’ as the “peacetime equivalent of a war crime” falls short in two regards. First, because wartime and peacetime are so culturally distinct (“all’s fair in love and war”), it would be as easy to just define ‘terrorism’ as to translate a war crime into peacetime. Second because in the age of militancy definitions and declarations of ‘war’ are unclear as non-state actors and clandestine organizations take on larger states using physical and cultural guerilla tactics – if we are fighting a “War on Terror” then surely our soldiers are wartime combatants, if we are organizing a global policing action then are our own actions in killing opponents ultra vires?

Finally, and perhaps by now unsurprisingly, many prefer not to use the term at all. Jason Burke, author of Al-Qaeda: the True Story of Radical Islam and a ‘terrorism’ expert, prefers the word “militancy” to describe the situation rather than specific acts. Foreign Affairs magazine, the journal of record for international conflict, refuses to use the term at all because of the inescapable stance it implies; one of its editors even explicitly called it a political word. Not surprising, given the “War on Terror” and what it means.

What is going on? First, the term’s ambiguity feeds its politicization. A fighter one likes is a “freedom fighter;” one who is disliked is a “terrorist.” Israel fights “terrorists” in Lebanon — or commits “state terrorism” in the West Bank. Depending on one’s stance Al-Qaeda operatives are “terrorists” on planes, or are “freedom fighters” against the US hegemony. Is a Hamas jihadist a terrorist if he only attacks soldiers? To Israel, yes; to others, no. Thus to apply the word to a given party is, essentially, to take a stand regarding it.

Second, political terms are misused deliberately all the time. This is not just some Orwellian nightmare or a paranoid reading of awkward bureaucratic phraseology. Nor is it confined to combatants. Rather, it has been a stated and explicit objective of Republican leaders since before even the first bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993. In the GOPAC memo “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control.” Newt Gingrich (http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article4443.htm) provided a list of useful words and phrases to use against opponents regardless of their policies, positions or context. Perhaps this Machiavellian disregard for substance is just common sense, but it has worked quite well. Indeed, the difference is often quite subtle; the continued Republican refusal to allow others linguistic self-determination is still very much alive in their characterization of the Democratic Party as the “Democrat” Party (see http://www.newyorker.com/talk/content/articles/060807ta_talk_hertzberg): a subtle difference, but a deliberate one.

====

Third, this malformation of language is, in a sense, the point of terrorism itself. The point of terrorism is to change the world in which we live, politically and culturally. As Orwell dramatically demonstrates in 1984, the way that these changes are most obviously, tangibly, and immediately manifest is through the language we all use. The transformation of our language is the message that terrorism is sending and our attention to the ethics of linguistic integrity is our first non-controversial anti-terrorist activity.

Finally, the term “terrorism” supposedly refers to a tactic, or an act — but in fact it is the context which separates a “terrorist” from a “freedom fighter.” In our dislike – even hatred – of specific terrorists we often forget how easy it is to like those terrorists with whom we agree, whether they be Guy Fawkes, the Stern Gang, or even, for some on the far left, the Palestinian and Iraqi “resistance” movements. In the Wachowski brothers’ recent V for Vendetta we are strongly encouraged to identify with the eponymous masked militant. The safe marquee names of Hugo Weaving (V) and Natalie Portman (Evey Hammond) seduce us to reassurance with their presence while the science fiction atmosphere of the film obscures the true violence at the core of the film. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist however, and V’s suicide attack on the British minister, however balletically staged, was the deliberate and planned murder of a governing official. V’s crowning glory likewise is the destruction of the Houses of Parliament by a train packed full of explosives. As we try to think about definitions and descriptions of ‘terrorism’ we must remember that they should fit, or accurately distinguish between both V and Al-Qaeda.

Finally, the term “terrorism” supposedly refers to a tactic, or an act — but in fact it is the context which separates a “terrorist” from a “freedom fighter.” In our dislike – even hatred – of specific terrorists we often forget how easy it is to like those terrorists with whom we agree, whether they be Guy Fawkes, the Stern Gang, or even, for some on the far left, the Palestinian and Iraqi “resistance” movements. In the Wachowski brothers’ recent V for Vendetta we are strongly encouraged to identify with the eponymous masked militant. The safe marquee names of Hugo Weaving (V) and Natalie Portman (Evey Hammond) seduce us to reassurance with their presence while the science fiction atmosphere of the film obscures the true violence at the core of the film. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist however, and V’s suicide attack on the British minister, however balletically staged, was the deliberate and planned murder of a governing official. V’s crowning glory likewise is the destruction of the Houses of Parliament by a train packed full of explosives. As we try to think about definitions and descriptions of ‘terrorism’ we must remember that they should fit, or accurately distinguish between both V and Al-Qaeda.

Context, of course, is the difference. Yet context is exactly that which is missing the moral simplifications of defining terrorism. In the rush for the moral high ground all sides have overreached for historical and religious language that will back up their claims. The most obvious example of this has been the mislabeling of this conflict the “War on Terror.” Echoing FDR’s famous phrase “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” it actually betrays the spirit of that statement by focusing on terror, the emotion, as an external, rather than internal, enemy. Moreover, while “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” implies that we should not be frightened of fear, the “War on Terror” implies that we should be terrified of terror.

Nor is the “War” exactly clear. Terrorists are de facto non-nation state actors (even in Iraq and Afghanistan the military actions were taken against illegitimate regimes rather than against the states per se) but, as the linguistics professor James Lakoff points out “[r]eal wars are wars against countries… in the ‘war on terror,’ we are attacking countries. But those countries are not the same as the terrorists. We’re acting at the wrong level.” (http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/08/25_lakoff.shtml) As for whether we’re at war, well, my high school students seem to believe that we are in a state of war and even the New Yorker seemed to acquiesce in this media misconception by publishing a series of “life at war” vignettes a few issues ago. It might be a good idea for Presidents to adopt war powers to fight metaphorical wars against poverty, racism, sexual inequality, or drugs but there is as little chance of finally defeating any of those other abstract enemies. Until we know who these ‘terrorists’ are, we will be fighting our own states of mind. As Lakoff succinctly puts it: “There’s no peace treaty with terror.” Terror, then, is its own self-perpetuating war, in which all enemies are labeled terrorists, and thus, in a circuitous and tautological move, all enemies everywhere are terrorists simply because they are enemies.

Finally, victims, too, are often hard to define exactly. In a simple military attack, the casualties are soldiers and they are an accepted, if unfortunate, result of war. In terrorism, there is a spectrum of complicity that is rarely discussed. Troops killed in Iraq after the fall of Saddam and those killed in the attacks of 9/11 or 7/7 are clearly not the same type of target as innocent civilians — and yet both of these groups are classifiable as victims of terrorism. Indeed, even civilians are not always so “innocent.” Saying that oppressed people need to be freed from tyrants (i.e. when the leaders and the people are not identified with one another) implies that peoples in representative countries are responsible for their leaders’ actions (i.e. when leaders and countries are identified). Shareholder responsibilities apply as much, if not more, to national citizens where the stake is in the patria rather than in the company. At the same time as terrorist violence is occurring, destruction is happening on a much larger scale as wars are being prosecuted in our name by nation-states (and environmental destruction is being carried out in the name of shareholder profits). The Nuremberg trials showed that there is a scale of complicity in all regimes – if we define an aspect of ‘terrorism’ as the murder of non-combatants then we need to define and grade the term ‘combatant.’

2. The Media are the Messengers

Terrorism is not a single action like murder or slander, but a complex system of actions. Unlike a military conflict where the action is its own strategic reward, a terrorist event includes a double chain of events. Broadly speaking, the first includes the threat or violence of an attack, and the second its reception by a wider audience. In the first chain someone (a ‘terrorist’) does something (threatens, attacks) to someone else (a “victim”). This action then provides the momentum for the second chain of events, in which something (the news media) does something (reports, comments) to someone else (the audience) who will be changed in some way. This is not to suggest that the news media is a party to terrorism, but we are a necessary link in the chain of events that lead from terrorists to the change they want in their desired audience. Our obligation to report and comment on the events of the world around us comes with a responsibility, because it is the link in the chain of terrorism which transforms the threat or violence into a changed culture of perception.

The first stage of terrorist actions are normally described as being either a “threat” or an “attack” — or perhaps as being either “verbal” and a “physical” attack. The former is extremely difficult to define and the latter is usually taken for granted. But, as the Weathermen showed in the 1970s, even in the latter category there is an important distinction between attacks on people and attacks on property. Although both are illegal, and despite a centuries-long western fetish for material property, violence to people is clearly, and legally, much worse. Not least because there is, beyond the elite of the global upper-class, a fantastically broad consensus that property is unethically distributed, there is little sympathy for the material (as opposed to symbolic) effects of attacks on property.

The difficulty in discussing the verbal rather than physical attacks is that the use of language as a tool of militancy conflates the first and second chain of terrorism. Although the threat (or sometimes “credible threat”) is aimed at an audience other than the explicitly threatened, the threat itself exclusively symbolic rather than actual. This means we must distinguish between predictions, fictions, precautions, dissensions, and specific threats although they all have similar effects on the final audience. The confusion of these genres has led to unhelpful accusations of betrayal on all sides. For example, as many have noted, the US media (not to mention the government’s National Threat Level) has done an extremely good job of keeping ‘terrorism’ front and centre of its audience’s attention – one of the intentions of the militants. Without a clear generic distinction (or open debate about the distinction) between the “verbal attack” or “threat” and these other forms of public discussion of terrorism, open societies will continue to be embroiled in unseemly, and unhelpful internal bickering leading to that loss of free speech which is another of the militants’ goals.

The violence of terrorism is, in part, symbolic. The strength of the symbol is proportional to the outrage it provokes, which comes from the very real pain it causes, but the intention of that pain is always primarily symbolic – aimed at the wider public  who will receive the news and turn it into pressure for change. The second half of the chain of a militant action is how it is received by the public at which it is aimed, rather than the victims who are attacked. This means that the impact of an act of terror is always mediated rather than direct: the target of the violence is never the final target. Al-Qaeda blew up the London Underground (and bus) not because they have an extreme aversion to British public transport but because they wish to prove a larger (if incoherent) point about Islam and post-colonial politics. Likewise, Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Oklahoma federal building was not because he wished to stop those federal employees housed inside from completing any specific tasks but because he wanted to make a symbolic point about the intrusion of the federal government (specifically the Bureau of Firearms, Tobacco and Alcohol) into the lives of U.S. citizens. And in the world of film again, and unlike in a military campaign where troops attack targets for strategic military gain, V blows up the Old Bailey in V for Vendetta because he wants to show that British justice is dead.

who will receive the news and turn it into pressure for change. The second half of the chain of a militant action is how it is received by the public at which it is aimed, rather than the victims who are attacked. This means that the impact of an act of terror is always mediated rather than direct: the target of the violence is never the final target. Al-Qaeda blew up the London Underground (and bus) not because they have an extreme aversion to British public transport but because they wish to prove a larger (if incoherent) point about Islam and post-colonial politics. Likewise, Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Oklahoma federal building was not because he wished to stop those federal employees housed inside from completing any specific tasks but because he wanted to make a symbolic point about the intrusion of the federal government (specifically the Bureau of Firearms, Tobacco and Alcohol) into the lives of U.S. citizens. And in the world of film again, and unlike in a military campaign where troops attack targets for strategic military gain, V blows up the Old Bailey in V for Vendetta because he wants to show that British justice is dead.

In all these atrocities innocents died, and died tragically, but the tragedy of their particular deaths only served to underscore the terrorists’ intention – it could have been anyone who was killed in these attacks. As Gore Vidal pointed out in September 2001’s Vanity Fair, “The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh,” (http://www.geocities.com/gorevidal3000/tim.htm) acts of terrorism are about meaning. We can agree or disagree with Vidal’s description of what he (or anyone) thinks McVeigh (or any terrorist) meant, but the argument should always be about the ideas and symbols involved. Vidal’s comparison of Timothy McVeigh to Paul Revere (also in 2001) is a salutary reminder that not all laws are just and that the line between heroes and villains is not always sharply drawn.

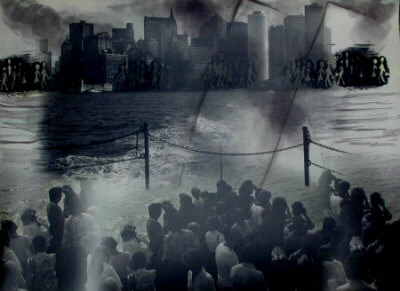

Damien Hirst’s comments on the first anniversary of 9/11 (see this article discussing them in Zeek) pointing out, of the plane attack “that it’s a kind of artwork in its own right” won him a slating in the press but he was, in this case, accurate – and, in context, not even particularly controversial. The attack, he said, “was wicked” but was “devised visually… for this kind of impact.” However incoherent the massage of the attack (and logical coherence is hardly a prerequisite for great art either) the image of the twin towers toppling meant that it was an incoherence searingly felt.

====

Since terrorism is symbolic, and its actual victims only stand-ins for the larger intended pool of victims, an effective “war on Terror,” i.e., a war on militancy, must be fought on three separate fronts: law enforcement, legislative process, cultural advocacy. Put another way, we need to defend our societies from illegal acts of violence, implement and improve the reasons why our societies deserve to be defended, and explain or demonstrate those reasons.

During the Cold War, the USA won the war of marketing. Despite the brutal Stalinist massacres, purges, and oppressions of the USSR, it was by no means clear that the union founded by the people’s revolution against the Tsar would lose a war of ideas to a country barely emerging from the shadow of racially discriminatory voting laws run by a moneyed white elite.

Now, however, America is badly losing the marketing battle. For Americans, 9/11 was a savage attack on what has become known in the US as the “homeland;” for much of the world it was a blow (notwithstanding its wickedness) to the hubris of a country whose national baseball championship is the World Series, and who built this World Trade Center and World Financial Center in its own backyard. My point, like that of Hirst, is not that the terrorists were justified (they were not, they are not) but that they were, like an artwork, effective in a symbolic way. The response of the West to that attack and to others that followed have been ineffective symbolically leaving audiences of the world, as a consequence, extremely sensitive to militancy. I believe that the western democracies are far from perfect but have right on their side, but – the merits of the draconian security measures (the Patriot Act in the US, the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act (ATCSA) in the UK, the Anti-Terrorism Act in Canada etc.) wars and nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan aside – we have not shown it symbolically. What we have shown is not engagement with ideas, but imposition of our pre-existing beliefs through power, domestically and internationally. We have tightened our second half of the chain and, rather than it strengthening us, it has made us more vulnerable.

Now, however, America is badly losing the marketing battle. For Americans, 9/11 was a savage attack on what has become known in the US as the “homeland;” for much of the world it was a blow (notwithstanding its wickedness) to the hubris of a country whose national baseball championship is the World Series, and who built this World Trade Center and World Financial Center in its own backyard. My point, like that of Hirst, is not that the terrorists were justified (they were not, they are not) but that they were, like an artwork, effective in a symbolic way. The response of the West to that attack and to others that followed have been ineffective symbolically leaving audiences of the world, as a consequence, extremely sensitive to militancy. I believe that the western democracies are far from perfect but have right on their side, but – the merits of the draconian security measures (the Patriot Act in the US, the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act (ATCSA) in the UK, the Anti-Terrorism Act in Canada etc.) wars and nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan aside – we have not shown it symbolically. What we have shown is not engagement with ideas, but imposition of our pre-existing beliefs through power, domestically and internationally. We have tightened our second half of the chain and, rather than it strengthening us, it has made us more vulnerable.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, filmmakers, more than politicians, understand terrorism as spectacle, and the media’s role in it. For example, in Steven Spielberg’s recent film Munich the initial sequence weaves the global media coverage of the 1972 Olympics into the opening action of the film, implicating international television especially in those terrorist events. In his main departure from George Jonas’ book on which it is based (Vengeance: The True Story of an Israeli Counter-Terrorist Team), Spielberg suggests that the establishment of the global media – spanning Europe, Israel, America, and the Arab world – is what marks the current period of terrorism from previous periods. No longer are attacks staged purely for a local population: all attacks are both local and global. At the start of the film action shifts back from the events in Germany to their reception by Israelis, Arabs, and Americans. In each of the different countries the commentary and subtitles put a different spin on the images – explaining, on many occasions incorrectly, what the images mean, whilst purporting to be purely factual. What is more telling than either images or spin, however, is the involvement of the television in the events, not only for the viewers but also for the protagonists. Media is not only global it’s also instantaneous and being beamed not only across the world but also onto the television within the apartment where Black September was holding the Israeli athletes. Although previously well documented, the failed rescue attempt is framed here by Spielberg as part of the complicity of the media in the culture of terrorism. This is not to say that the networks deliberately foiled the attempt to storm the apartment by showing pictures of fake athletes carrying guns into position and snipers taking up position on surrounding roves. Rather they were in positions where they could hardly help but affect the action and its reception. The conflict is both formed and framed by its coverage. Munich pairs pictures of the dead athletes on public television with pictures in a private room being sorted for assassination – assassinations for public consumption. Retribution, as the Israeli war council is portrayed as saying, is not about Arabs in training camps (already bombed quietly) but about fixing the world’s attention.

Although reiterated by Spielberg for this generation, the dichotomy of local and global mediated and homogenized by mass media was recognized earlier by John Frankenheimer in Black Sunday (1976), a thriller made in the post-Munich era of terror. Again drawing on a set of global and historical injustices Vietnamese, Japanese, Germans, and Arabs join together in planning an attack on America that is designed to wreak maximum havoc on primetime television. Uncannily presaging the death-from-the-air of 9/11, the Goodyear blimp threatens death when it jettisons its usual TV cameras to shoot the event with 250,000 steel darts. Dahlia Iyad (Marthe Keller) expresses the symbolic nature of the equality to which militants aspire and hope that this action will lead: “The American people have remained safe through all the cries of the Palestinian people. People of America, this situation is unbearable for us. From now on, you will share our suffering.” As always, Palestinians are a cipher for the oppressed of the world and it is the militants’ aim to make Americans feel their pain.

Until western polities find a symbolic language, or languages, to express their meaning, or meanings, and inspire the world in a more substantial way than the hollow repetition of the word “democracy” we will continue to lost the initiative in the global struggle between moderates and militants. We are in real danger of seeing terror move away from fanatic terrorist sects with fairly well-defined aims to the fantasy affiliations of the Columbine demographic. The current bland homogeneity of corporate-sponsored youth culture with its processes of instant appropriation is in danger of making terror – that which cannot be appropriated by the establishment – the new rock ‘n’ roll. Opposing this is not merely the job of politicians, it is the job of artists, musicians, writers. Forget patriotic spending, not selling out is now a cultural imperative.

3. Conclusion: Violence Works

Violence works. If violence did not work it would be easy to condemn — as lazy or ignorant, as well as immoral. But in fact, militancy is perpetuated because it is, historically speaking, effective. In those cases where violence does prove effective those who use it win power for themselves or their allies who then, from a more established and historical position, talk of their previous violent actions as part of a necessary struggle. In this way violence is inscribed into politics as an acceptable, and even glorious, necessity. As Hannah Arendt puts it “the practice of violence changes the world, but the most probable change is to a more violent world.”

The long-term problem that ‘terrorism’ poses is the disturbance of international politics as the crude nineteenth century political tool – the nation-state – breaks down. Slowly, but inexorably, the nation-state is being colonized, replaced, or appropriated: by non-representative organizations like GATT or the WTO, through local self-governance, by supranational bodies like the EU and the UN, and finally by the extremely violent and marginalized bodies like the Janjaweed, Al-Qaeda, even Robert Mugabe’s Zanu PF. These latter bodies and the strategies to oppose them can have a disproportionate (and unfair) influence on the shape of the new governing structures that are developing, and on the rigidity of the old ones, preventing their smooth transition.

When political regimes are overthrown by force – for better or for worse – violence is inscribed into the body politic. Once that happens it is difficult to gain legitimacy untainted by the influence of violence. Roberto Calasso traces some of the historical difficulties of legitimacy in his oddly powerful, and unclassifiable work, Ruins of Kasch. Political power relies on the proof of brute force and that means occasionally showing force which makes its existence hard to deny. If you are in charge of a regime or a system of government that traces its legitimacy to violent overthrow (a revolution, a civil war, a war of independence, a coup, a war of conquest) it is difficult to argue against the possibility of a ‘just violence.’ As Shakespeare puts it “This even-handed justice/ Commends the ingredients of our poison’d chalice/ To our own lips.” (Macbeth I vii)

The attacks themselves provide an occasion for legal prosecution and for outrage but, because terrorism works through symbolic effects, often the more ‘legal’ an attack, the less the outrage and the less the success. Thus the way to deal with this newly virulent type of political violence is to disaggregate and normalize it. This would seem to be impossible, since terrorism seems, on the face of it, to be incomprehensibly unacceptable — unthinkable, in a certain way. However, it is not really unthinkable, and ought to definable precisely in order to neuter its symbolic effect. Once the crimes are understood as “inciting religious or racial hatred,” “causing damage to property,” “endangering human life,” “slander,” or any of the other usual crimes or calumnies committed by militants, they are no longer beyond the pale of understanding and lose symbolic potency.

Such a definition is unlikely to happen, because it would undermine the current state of affairs, in which, like Humpty-Dumpty, politicians can label as terrorism anything they like. What Humpty-Dumpty is really asking for, in his refusal to define his terms, is power — the power to shape reality through language, rather than work within an agreed upon framework of concepts and coherence. As Humpty himself said, “The question is… which is to be master – that’s all.”