I found God hanging out innocuously on a page of my Talmud within an obscure legal debate over whether or not a twisted wick is still suitable for kindling Shabbat lights. I glimpsed God slipping between a convoluted argument in a passage about the specific width and length of willow fronds used as a part of a ritual that no longer exists in a holy Temple that no longer stands. I even caught a peek of God hanging out on a page of Talmud that went over the minutiae of how to remove infant feces from your house on Shabbat.

I found God hanging out innocuously on a page of my Talmud within an obscure legal debate over whether or not a twisted wick is still suitable for kindling Shabbat lights. I glimpsed God slipping between a convoluted argument in a passage about the specific width and length of willow fronds used as a part of a ritual that no longer exists in a holy Temple that no longer stands. I even caught a peek of God hanging out on a page of Talmud that went over the minutiae of how to remove infant feces from your house on Shabbat.

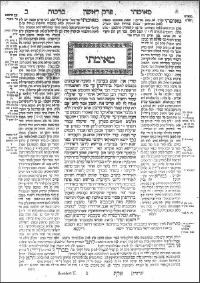

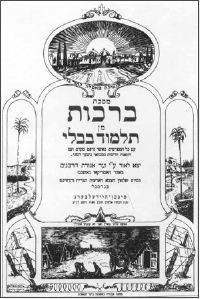

The Talmud is the compendium of Jewish oral law and folklore that was composed between the 2nd and 7th Centuries of the Common Era. There is a Talmud of the Jews of Babylon (which is more commonly studied) and a Palestinian Talmud from the Land of Israel. From the first moment that I encountered the Talmud’s squat letters and bizarre logic, I have found traditional Jewish text study more spiritually gratifying than any other religious practice. And I had a lot to compare it with. I was raised Tibetan Buddhist by parents who were cultural Jews, who exposed me to meditation, chanting, yoga postures, Hindu devotions and spiritual pilgrimages all before the age of six! I was always something of a holy roller and enjoyed all of these activities, but it wasn’t until I encountered Talmud study in my early twenties that I first felt a sense of spiritual fulfillment.

I am obviously not alone. For hundreds of years, Jews in every historical period and geographical location have devoted hours upon hours, weeks upon weeks, years upon years, to the study of the Talmud. It is said that poring over the Talmud has sustained our spirits through centuries of oppression. Traditional text study is held to be as important as all the rest of the mitzvot (religious commandments) combined. Today, however, Talmud study is often rejected or at least regarded with some suspicion by \ post-modern, progressive Jews because it is, and has always been, an elite activity.

Talmud study requires an array of linguistic, educational, and social tools which in the past were widely available to well-to-do Orthodox men, but to few others. Today it is still difficult for women, transgender people and queers to even find the teachers and tools to engage in text study, and nearly impossible for poor folks who cannot afford this highly specialized instruction. As a newly ordained rabbi working in progressive communities, I often find it very difficult to explain why we should even try to invest the time and energy that is necessary to study the Talmud ourselves and to strive to open the door to Talmud study to those in our communities who are currently excluded from text study. The usual reason, that Talmud is our heritage, doesn’t work. An inheritance is only valuable if there is some content to it; something that can continue to speak to and enrich contemporary lives.

Talmud, unlike the sacred texts of other traditions, does not deal with exalted topics and grand narratives. Unlike the Bible, there are no stories of escaping slavery or journeying through the wilderness. In fact, God’s proper name is never mentioned. Instead, the Talmud is entrenched with the nitty-gritty details of life, and discusses those details in a manner that to many progressive Jews is frustrating at best, offensive at worst.

As a student of Talmud and a teacher of progressive Jews, it is my goal to “open” the dusty tomes and reveal their relevance to my community. To do that, I have found we have to change the way we think about learning.

One of the difficulties for modern people first encountering traditional Jewish learning is that all of us 21st century people were educated to see learning as goal oriented. We discovered in elementary school that you learn biology in order to find out how plants and people are made, you learn English in order to know more about great authors and their insights into human nature, and you learn history in order to understand the events and trends that have shaped our world. Early in our educational lives we learned what learning is: a means to acquiring facts and accruing information. Some of this information might inspire us to live better lives, create beautiful things and contribute to the world. But learning itself, no matter haw exalted it is, is still largely viewed as a means to an end.

Jewish learning on the other hand is an end in itself. Our tradition teaches us that religious study ought to be “lishma,” for its own sake. Judaism cautions us against using the Torah as an ax to dig with.In other words, we must not learn as a way to reach a goal, even if that goal is a worthy one. In Hebrew sacred study, limmud, is distinct from goal-oriented education, hinuch.

If we approach the Talmud expecting to learn from it as opposed to with it we will be disappointed. As a source of information, the Talmud is remarkably poor. If I were to line up all the facts I have gleaned from hours upon hours of Talmud study I would come up with a pretty motley list: a rag used for scrubbing toilets is still susceptible to ritual impurity if it is kept in a box but not if it is thrown in the trash, we dug pits and covered up our feces in the desert when we were on the way to the Promised Land, the altar used for daily animal sacrifices in the ancient Temple was only washed once a year…

If we approach the Talmud expecting to learn from it as opposed to with it we will be disappointed. As a source of information, the Talmud is remarkably poor. If I were to line up all the facts I have gleaned from hours upon hours of Talmud study I would come up with a pretty motley list: a rag used for scrubbing toilets is still susceptible to ritual impurity if it is kept in a box but not if it is thrown in the trash, we dug pits and covered up our feces in the desert when we were on the way to the Promised Land, the altar used for daily animal sacrifices in the ancient Temple was only washed once a year…

Certainly some of the information that I have learned has been sublime (unicorn skins were used in the building of the Tabernacle) or inspirational (we must not do to our fellow what is hateful to us). However, the information in the Talmud is also often offensive (a wife can be purchased through money, sex or a written document.) Although I have learned many interesting things about Judaism from Talmud study that is not what motivates me to return to the table day after day. I learn Talmud in order to simply learn, not to learn about something. It is the process of learning that fills my mind and nourishes my soul. Like prayer or meditation, Jewish learning is a spiritual experience in and of itself.

Learning Talmud is a spiritual experience that can enrich the lives of postmodern Jews for a number of reasons. First of all, Talmudic texts are so complex and intricately woven together that just following the flow of the arguments takes total concentration in the present moment. I spent years trying to meditate and struggling to find mindfulness in the midst of intrusive thoughts from the past and nagging worries about the future. But when I sit down to learn a page of Talmud I am wholly in the present – there is simply no room in my mind for past or future concerns. I am utterly caught up in the complex and strangely beautiful flow of the arguments. The Talmud follows the “order of the heart” not the “order of the mind.” Thus to follow its flow it must be read from deep within our own hearts, a post-cognitive place where the past and the future slip away. To translate this experience into the language of my New Age childhood: Talmud study finally showed me how to “be here now.”

The complexity of the Talmud is due in part to the fact that is filled with a cacophony of voices representing divergent opinions and spanning generations. Each page is chock full of people, each one of whom is unique, named, and respected. In order to even begin to understand a page of Talmud, I must first strive to listen to the voice of each of the luminaries on the page. When I learn Talmud I am called upon to traverse the boundaries of time, place and gender and truly listen to the perspective of a Rabbi from 6th Century Babylon or 2nd Century Palestine. Furthermore, Talmud is traditionally learned in chevruta, with a living study partner, whose voice I must also be attentive to and whose reading I must struggle to comprehend. Talmud study is a model for ethical encounter in any context – it begins with listening. Many of us would rather not listen. We would prefer to forget our vulnerability towards other people and the demands they make upon us, but Talmud study as a religious obligation reminds us that a spiritual life is a life spent paying close attention to one another.

The complexity of the Talmud is due in part to the fact that is filled with a cacophony of voices representing divergent opinions and spanning generations. Each page is chock full of people, each one of whom is unique, named, and respected. In order to even begin to understand a page of Talmud, I must first strive to listen to the voice of each of the luminaries on the page. When I learn Talmud I am called upon to traverse the boundaries of time, place and gender and truly listen to the perspective of a Rabbi from 6th Century Babylon or 2nd Century Palestine. Furthermore, Talmud is traditionally learned in chevruta, with a living study partner, whose voice I must also be attentive to and whose reading I must struggle to comprehend. Talmud study is a model for ethical encounter in any context – it begins with listening. Many of us would rather not listen. We would prefer to forget our vulnerability towards other people and the demands they make upon us, but Talmud study as a religious obligation reminds us that a spiritual life is a life spent paying close attention to one another.

If I truly listen to each of the voices embedded within Talmudic texts I might hear things that I would miss if I don’t pay close and respectful attention. For example, if we listen to the voice of each disputant in the debate surrounding the prosaic issue of the twisted wick we can hear surprising things. The Rabbis in this text want to know to what extent a garment can be twisted into a wick and still retain its essence as a garment. Underlying this question there are a number of deep psychological and social concerns. How and when is the old transformed into something wholly new? What are the boundaries around continuity and innovation? How much twisting/transforming can we sustain and still retain our identities as individuals or as a people?

In addition to forcing me to listen to the voices of other people, Talmud study as spiritual practice teaches me to pay close attention to the world that surrounds me. A page of Talmud is not just filled with other people. It is also filled with things: twisted wicks, insignificant rags, millstones, willow branches, animal skins, scattered fruits, freshly laid eggs, pickled fish and precious stones. In order to understand a page of Talmud I must be paying close attention to the world: to the angle that willows grow in, the shape of a twisted lamp wick and the moment when a rag is no longer useful. This is the stuff of Jewish sacred text and Jewish sacred living, the everyday details that surround us. Talmud study as spiritual practice is not just about being in the present and listening to other people, it is also about the sanctity of the mundane. The holiness that resides in dirty rags and infant feces!

There is yet one more reason why I believe that Talmud study can be a spiritual practice that is meaningful for postmodern Jews. In order to understand an argument I need to mimic the Rabbis of the Talmud and explore infinite possible solutions. In order to understand the Talmud’s debate concerning whether or not a twisted wick is suitable for kindling Shabbat lights, I had to consider that they were actually discussing a case when the wick has been twisted out of a garment that is exactly three by three fingerbreadths, and the Sabbath under scrutiny happened to also be a Festival. To hit upon such extreme specificities, one must first explore universal possibilities. In other words, it hinges upon openness to infinity.

A few years ago I was in the audience watching a master acrobat perform. Suddenly she appeared to tumble down from a height of ten meters, hurtling towards the floor, yet spinning elegantly all the way. The audience held its breath in suspense. But shortly before she hit bottom she froze a few centimeters from the ground. At that moment it became clear to us that she was actually suspended on a wire, held safely within an external structure. Talmud study as spiritual practice gives me the same feeling in my mind as this acrobat achieved with her body – it allows me to freely explore the infinite possibilities of my world, to elegantly spin through space, and at the same time know that I am actually safely connected to the “wire” of Jewish sacred tradition.

A few years ago I was in the audience watching a master acrobat perform. Suddenly she appeared to tumble down from a height of ten meters, hurtling towards the floor, yet spinning elegantly all the way. The audience held its breath in suspense. But shortly before she hit bottom she froze a few centimeters from the ground. At that moment it became clear to us that she was actually suspended on a wire, held safely within an external structure. Talmud study as spiritual practice gives me the same feeling in my mind as this acrobat achieved with her body – it allows me to freely explore the infinite possibilities of my world, to elegantly spin through space, and at the same time know that I am actually safely connected to the “wire” of Jewish sacred tradition.

The debate about a twisted wick, came down to trying to discover whether or not it was suitable for kindling Shabbat lamps. In other words, was it an appropriate way to bring kedusha, holiness, into the world? Although God is rarely discussed explicitly in the Talmud, the texts are filled with holiness: the holiness of the moment; the sacredness of everyday objects; the sanctity of the voice of another person; the divinity within our encounters with infinity. Each time I open my Talmud I learn to see more holiness in the people and things that surround me. I find God in a twisted wick, in a tattered rag, in the opinions of my teachers and study partners and in the voices of the street filtering in through the window of my study all.

Images: The Seeker and Shunyata (Emptiness) by Mary DeVincentis. Lower Talmud page from an edition printed by Holocaust survivors immediatly after their liberation.