I don’t care about food. Sometimes, I’ll forget to eat until three or four in the afternoon, at which point I’ll go to one of two cafes and get the same sandwich I always get. I often have the same meals day in and day out, with only the slightest variety in high-carb intake: instant mashed potatoes, seven minute pasta, raw cookie dough. If I ever tell you I’m going to cook for you, it will be a grilled cheese sandwich, maybe with a flourish of avocado if I’m feeling fancy. Beyond, needing it to live, food is just not a priority.

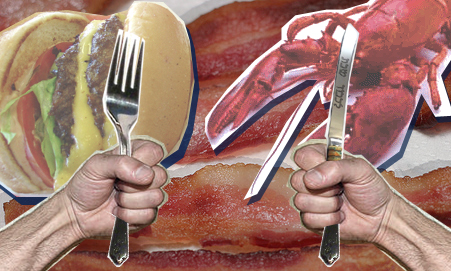

Growing up, however, I was told that God cared very, very much about what I ate. It was so important that God, and rabbis doing his bidding, created an elaborate set of rules to make sure I kept my body pure. Keeping kosher (kashrut, whatever) is ultimately the greatest divide between Judaism and Western Society, a day-to-day reminder that to be Jewish is to Not Be other things. Big Macs are not yours, Red Lobster is not yours, the food of a hundred other cultures from a hundred countries is not yours, nor are you to touch a piece of it. You have kugel.

I still keep kosher. I have, however, given up most of the other religious beliefs I was raised with. That makes me a kosher atheist, and I’m not the only one. A recent profile of Ezekiel Emanuel, wonder-doc and brother of Rahm and Ari, reveals that he, too, is an atheist who keeps kosher. Lisa Miller picked up on this, and questioned his eating habits in the Washington Post. Determining that Emanuel’s own reasoning is “wobbly,” she concludes that the real reason an atheist would observe these dietary laws is because—wait for it—they aren’t atheist at all! Rather, keeping kosher is a way to remain in contact with the “transcendent parts of life,” whatever those are. It’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to be an atheist. She writes:

Usually when a person ditches religion, he or she also happily ditches the antiquated rules and regulations that go along with a strict observance of faith. Good-bye, stupid rules about who can have sex with whom, and under what circumstances!

Really? That’s what people are thinking about? I’d never claim to speak for anyone else, but my own coming out as an atheist was nothing but painful. I grew up in a proud, loving, religious community. Every aspect of my identity was defined by a religious Judaism: not just who my friends were, but every person I knew, and every activity I participated in. Maybe there’s nothing unique about being raised religious in America, but I remember every detail of it. A lot of that rests on food: Friday night dinners, seders, getting the toys from Happy Meals without the burger.

I also remember slowly starting to realize that none of it was for me. As a kid, I had assumed that no one actually prayed, and when I realized otherwise, it started to become clear the whole God thing wasn’t for me. The summer before college, the big question among the students at my yeshiva was who would stay religious and who wouldn’t. For many, the answer was clear: some were already sneaking in trips to In N’ Out Burger during lunch breaks, and others were going to Israel. It wasn’t until I entered my college dining hall, 3,000 miles away from home, that I first grappled with the question myself.

Faced with endless food options, I backed myself into a pizza-filled corner. I had no fully formed opinions about religion, but figured that I could play it safe by eating only pizza. Breakfast, lunch and

dinner, that’s pretty much how it went for that first year. On spiritual autopilot, my only real crisis came when I won concert tickets—for a Friday night show. Panicked, I called a high school friend, who asked me to weigh what was more important: one night’s fun or 5,000 years of tradition. It was an odd comparison, I thought, but I ended up choosing the latter.

Soon after that, a family friend back home, and a pillar of our synagogue’s community, died suddenly. I ran to American University’s Kay Spiritual Life Center to pray, but as soon as I opened the siddur I realized I felt emptiness in what I was doing. These were words written by wise men from the Middle Ages who didn’t know the man who died, and, even more disturbing, I knew their words were going nowhere. The idea of existence beyond the grave felt, first and foremost, false. All my past hesitations with religion suddenly made sense. I left the Spiritual Life Center knowing that I had no use for it anymore.

There wasn’t any joy in that, at all. No vitriolic triumphalism, no throwing the rule book in anyone’s face, just the knowledge that God wasn’t (and still isn’t) an idea I could accept. It was a very depressing thought, honestly. It led to hours-long conversations with my parents, since I was convinced that with one more explanation of the Jewish people I’d finally understand the concept of faith. I tried to embrace secular Judaism, a disaster which left me crying in a bookstore holding a copy of Hannah Arendt’s Jewish Writings. All I had left were the rules.

And then those fell, one by one. Keeping Shabbos was the first to go; the joys of Saturday Netflix came easily. Hanging out with a mainly Jewish crowd also quickly fell out, as all the kids who went to the Hillel were assholes. It became clear that the thousands of years of tradition, from Moses to Sandy Koufax, just didn’t mean a whole lot to me.

The one thing that remained were those sticky dietary laws. They felt removed from the culture they had come from, as if my parents had conjured them out of thin air. I was lonely on the opposite coast, and picking out what I did and didn’t eat gave me a tangible connection back to the warmth of Los Angeles. Months became years, and I eventually realized that I had stopped eating meat altogether.

In the profile, Emanuel plays coy about why he still keeps kosher, stating that “Orthodoxy and orthopraxy are not the same.” I’m pretty pleased with that obnoxious non-answer, mostly because it reflects my own uncertainty as to exactly why I keep these rules. Acquaintances are routinely shocked (shocked!) when I tell them I’ve never had the slightest curiosity about oysters, pepperoni slices, or that holiest of holies, bacon. Maybe someday, but I doubt it. And my knowledge about vegetarianism extends as far as the liner notes to Moby’s album 18 (he makes a pretty convincing argument about utilitarianism and the world’s resources).

A friend suggests that Emanuel does what he does because “it annoys people,” which makes sense to me. It’s a way for us to embrace our parent’s traditions and communities on our terms. I wish Miller would look past hokey terms like “transcendental” to describe decisions to remain involved in religious communities. I eventually came to realize that just because I was giving up yarmulkes and the six hundred and thirteen mitzvahs didn’t mean I had to lie about who I had grown up with. Keeping kosher is a concrete way to keep alive the ties to the people who raised me—my parents, my friends, my first community. And there’s nothing more real than that.

Art by Margarita Korol