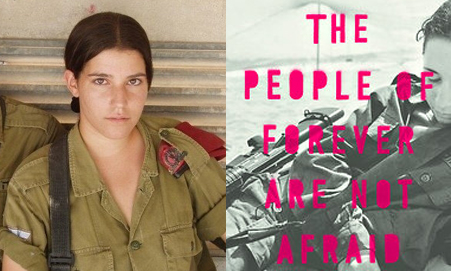

The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, the first novel by Shani Boianjiu, a 25-year-old Israeli who writes in English, has much to tell us about life in the Israeli military. The Israel Defense Forces is perhaps Israel’s most mythologized institution and, to outsiders, its most opaque. For young diaspora Jews, the IDF is often encountered through the sweatshirts purchased in a tourist shop—a popular method of vicarious identification—and by discussions with the occasional veteran, every one of whom, it can seem, has served in an elite unit. (The process of mythologizing, after all, also depends on non-Israeli Jews looking admiringly at a symbol of Jewish power.)

Boianjiu’s novel (some critics have referred to it as a collection of stories) digs beneath the hasbarista image of IDF service and offers a somber look at the depression and alienation that can arrive when one transitions from being an 18-year-old high school student to a soldier charged with securing your country’s periphery or enforcing its occupation of the West Bank.

The book is largely the story of three young women—Lea, Avishag, and Yael—friends from a small village near the Lebanese border. We get some impression of their life at home, where Avishag’s brother, Dan, committed suicide not long before she was drafted, but much of the novel is about their refracted, vastly different experiences. Lena joins the military police (she lobbied for a higher-status assignment, but her request was denied) and works at checkpoints in the West Bank. Avishag is sent to the Egyptian border, where she monitors surveillance feeds and does guard duty in an observation tower. Yael is a weapons instructor at a base near an Arab village, whose boys frequently sneak in to steal equipment.

It is a novel of contrasts, where the trivial and the tragic, gossip and gunplay, messily intermingle. One of the characters falls for a fellow soldier and they engage in furtive sex at their base; the next day, he’s sent to Lebanon and dies. Weeks of unending banality at the Egyptian border are interrupted by the sudden appearance of a car trafficking women, or of an African migrant shot while trying to cross into Israel.

Boredom, in fact, is the dominant theme—the book has this in common with the Gulf War memoir Jarhead—along with the ways in which it colonizes the mind, destabilizing these characters’ sense of self, making them long for some extreme sensation (love, terror, violence) to slice through the ennui. It’s that destabilization of the self, combined with the traditional insecurities of youth, which makes Yael, Avishag, and Lena blend together. They do have some individuating qualities—Lena is beautiful and cold; Avishag is scarred by the death of her brother, though Yael, who loved him, is as well—but in many ways are indistinguishable. It’s one of the novels deficits: the storylines may vary, but the characters peopling them do not.

All three women are suspended somewhere between adolescence and adulthood. IDF service is an interregnum in which they are supposed to find themselves, but for them the uniform promises a sense of purpose that it can’t deliver. This is reflected in the prose, a mashup between the lyrical and the chatty, blog-speak meeting finely tuned confessionalism. Consider the opening to a chapter narrated by Yael: “One day, thirteen days before the war, I turned beautiful. It was the best. Don’t let anyone tell you there is anything better that can happen to a woman.”

One day but also thirteen days—vague and then exact. Beautiful—an adult’s word. But “it was the best:” that’s how a teenager talks. Yet in the next sentence she reminds us she is a woman.

This miscegenated style is ultimately very effective for Boianjiu, as it reflects the kind of story we are being told. Boianjiu’s hybrid English—informed as much by American pop culture (Dawson’s Creek and Mean Girls get referenced) as by any formal instruction—produces some small, pleasurable dissonances, the kind that can only come from a non-native speaker. Avishag at one point remarks that “it is time to start caring about someone who is not myself,” which is a challenge for all three of these characters. An American would probably use the more conventional “other than myself,” a phrasing that would be digested without notice, like the chips at the bottom of the bag.

So why did Boianjiu write this novel in English, rather than her native Hebrew? In interviews, she’s explained that, following her IDF service, she studied English and social anthropology as an undergraduate at Harvard. The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, which began as her senior thesis, came together practically by accident. She was writing stories for class and a professor put her in touch with Andrew Wylie, one of publishing’s biggest agents.

Boianjiu’s career soon took off, well before this book was released. In 2011, she was selected for the National Book Award’s 5 under 35 prize, reportedly on the recommendation of Nicole Krauss, who has been a champion of Boianjiu’s work. It’s understandable why Krauss is a fan. Like her American admirer, Boianjiu leans towards direct, emotionally raw prose, she makes use of repetition, and the novel, even in its overall bleakness, is shot through with whimsy (like the sandwich shop in which customers can request any ingredients they can think of). There’s also an element of, if not outright surrealism, then a blurred vision, one that derives from the characters’ brokenness, their inability to fully engage with the world.

Early success has a tendency to attract both irrational criticism and unearned praise. It also makes for odd bedfellows. Some journalists have compared Boianjiu to Lena Dunham, a pairing that seems to have little merit except that both are female creatives in their mid-twenties. Perhaps Dunham is just too easily invoked—and too SEO-friendly—to resist. Recently, a rather cynical article in Haaretz called Boianjiu the “Cinderella of Kfar Vradim,” and deemed her the product of marketing hype (there really hasn’t been much).

Some of the venom seems to stem from the fact that Boianjiu writes in English, thereby bypassing the smaller Israeli market, but like Aleksandar Hemon, her decision to write in a second language has proven an artistically sound one. Debating the commercial or ethical merits of that choice is a rather dull side pursuit. Instead, better to conclude that Boianjiu has produced an impressive first novel, flaws and all. That she has done it at a comparatively young age only means, I hope, that she will have more time to perform the same feat again.

Boianjiu will be participating in a Twitter Book Club with Jewcy and the Jewish Book Council November 20 from 1:30 to 2:10 p.m.

Recent Kvetches: Stop Calling Porn Star James Deen a ‘Nice Jewish Boy’

Watching the Anti-War Documentary ‘Tears of Gaza’

The Jews of HBO’s ‘Boardwalk Empire’

Hello! I just want to provide a massive thumbs up for the wonderful information you’ve here for this post. I am returning to your website for additional soon.