Yael Katz Ben Shalom and Eyal Ben-Dov are members of Artneuland, an Israeli collective of leading artists, curators, theoreticians, and intellectuals. Primarily focused on photography and video, Artneuland adapts its name ["the new art land"] from a play on words on Theodor Herzl’s novel Altneuland (1902) ["the old new land"]. Artneuland promotes communal dialogue and confrontation amongst various steams of culture in and outside of Israel though ongoing creative projects, exhibitions, lectures, seminars, publications, and special events.

Yael Katz Ben Shalom and Eyal Ben-Dov are members of Artneuland, an Israeli collective of leading artists, curators, theoreticians, and intellectuals. Primarily focused on photography and video, Artneuland adapts its name ["the new art land"] from a play on words on Theodor Herzl’s novel Altneuland (1902) ["the old new land"]. Artneuland promotes communal dialogue and confrontation amongst various steams of culture in and outside of Israel though ongoing creative projects, exhibitions, lectures, seminars, publications, and special events.

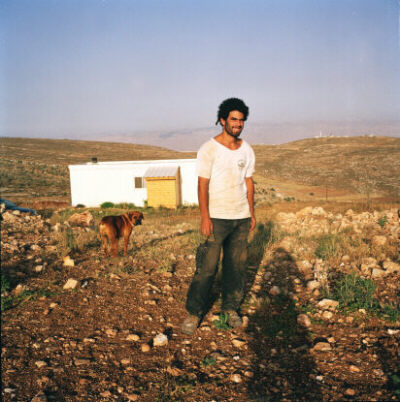

From its main offices in Tel Aviv, Artneuland launched two new programs in 2006. The first is a large cultural-arts space in the Mitte, previously of Berlin’s Jewish Quarter, serving as a platform for rotating exhibitions, symposiums and events. Shalom, who founded Artneuland, calls it "a meeting point amongst religions and nations." Ben-Dov directs programming for a second project, a five month residency in Israel for non-Israelis using photography and video to explore Zionism, Judaism, Jewish history and the role of art in society. The residency is co-sponsored by MASA, a cluster of long-term programs for adults initiated by the Government of Israel and the Jewish Agency (http://www.masaisrael.org/Masa/English/Programs/Artneuland.htm). The images accompanying this interview are the work of members of the Artneuland collective.

Zeek: Tell me about Artneuland as a play on words.

Yael: It is based on the novel Altneuland by Theodore Herzl from 1902. Art is an English word, an international world. Artneuland plays with the connection between "newness" of art and "oldness" of tradition in local environments.

Zeek: What is the specific connection between Herzl’s vision of a "Jewish utopia" and your work in the arts?

Yael: The new is the old and the old is the new. We are interested in breaking down the linear perspective that ideas exist in just one place and time. We are interested in the fragments of ideas we inherited. We take the tradition and combine it with new questions about East and West; Tel Aviv and Berlin, Israel and Diaspora, old and new…

Zeek: What is Artneuland’s work as a practice or an organization?

Yael: It’s holistic. We have an office in Tel Aviv and are opening an office in Berlin and our goal is to present Israeli culture with a Jewish identity as we experience it in Israel and abroad. We believe in a wide discourse with Islam and Christianity – an international dialogue – that takes place where this discourse needs to happen. Place is extremely important.

Zeek: Would it be fair to say that if Herzl’s vision was of a Jewish utopia in one place, yours is of a utopia that can travel?

Zeek: Would it be fair to say that if Herzl’s vision was of a Jewish utopia in one place, yours is of a utopia that can travel?

Yael: Yes, it’s a heterotopia.

Zeek: Do you think there is an Israeli artistic identity that travels?

Eyal: I see it as a matter of tikkun olam [healing and repair of the world]. It’s a vision of art and Zionism as a form to change humanity. It’s a revolutionary phase of art. Berlin is important for this reason because working in Berlin is about going back to the place of the catastrophe to change it through the revolutionary practice of art.

Zeek: The original concept of tikkun olam is that there was no way for the indivisible Divine to exist without plurality. Everything that exists is somehow part of brokenness because without brokenness there is no creation. So there must be endless reflections of the brokenness in the world in order for the world to exist at all. Yael: Yes, but I think you have to be careful because that idea belongs to monotheism, which can be very narrow. For me heterotopia and tikkun olam are about a deep understanding that if we want to make art we have to deal with problems. As artists we seek out the wounds in the world and expose with work. Art should expose problems.

Zeek: Do you think that Israeli art is somehow uniquely connected with solving problems?

Zeek: Do you think that Israeli art is somehow uniquely connected with solving problems?

Yael: It’s everywhere, but what we try to do is to take problems and to create a mission with artists to take a subject to operate within, to research it. And this is different from each artist in a studio generating meaning in their own work.

Eyal: I think it is very important to say that we emphasize photography – a form that relates to the place in which it the image happens. It’s a documentary form of art. It’s not an imaginary form; it focuses on realism. Also in video. We deal much more in documentary video. Yael: And with this form we put our attention on questions of ethics, social problems, history.

Zeek: How does the collective work?

Yael: We invite artists to participate in a process which is based on a model of interdisciplinary work. Theoreticians, architects, artists. They are all people at the top of their field and they meet and exchange materials and ideas to create a plan for work together in each project. We all work together on whatever problem we have chosen to confront. In the end there is a product responding to a problem and theme – an exhibition, a catalogue, an event.

Zeek: How is this different than the way that artists usually work?

Zeek: How is this different than the way that artists usually work?

Eyal: The modern way that most artists work is in a studio alone – not exchanging thoughts in the process of working on the art. Art today lives off of a modern myth that the artist is crazy. He’s connected to God. Maybe that is why he’s crazy. But he’s a loner and an outsider by himself. We are talking about the artist as a social worker. He is not a crazy person dealing with mysticism alone. He can, but we see the social role and responsibility of an art to show wounds and heal them with others.

Zeek: What is the artists’ responsibility then?

Yael: To create common activities for the society. For example, we initiated a program with the hi-tech firm Comverse in Neve Sharett, a poor area in Tel Aviv. The company wanted their workers involved in the community and the question was how. We offered them a program of teaching photography and art as a social tool. The Comverse people and the people from the neighborhood meet together and practice using their eyes together to understand their relations of identity and to the places they live and work. They understand the difference between eyes in Neve Sharett and their own neighborhood. A kaleidoscopic view is a dialogue to make a change and be aware.

Zeek: The whole idea of exposure of brokenness and weaknesses is a very interesting tie in with the forms of art you choose to work in.

Eyal: For me it’s a form of enlightenment in photography. It’s deep connection of creativity and education. Education is not about a degree. It’s a matter of self-creativity. Teach yourself your work with others helping you do it.

Zeek: Stereotypes of the artist as the outsider or crazy or connected to God are definitely not reflective of Israeli artists I know – secular, modern, not living in Israel…

Yael: If you only create your own circle and serve your own circle it makes you blind. We try to train the eyes – everyone has their own points of blindness – some of which we choose. You need to become aware of your blindness. Modernism created a deep blindness because it divided art from society. We try to bring art back to culture and society. The artist has to be a social activist by working in the culture.

Zeek: So you have a network of Israeli artists who come together regularly with ideas for projects based on social problem solving; a dedicated space in Berlin which is a kind of satellite for your work; offices in Tel Aviv; and now you are opening a program for people of outside of Israel to come to join your work. Tell me a little about the program and the problems it hopes to solve.

Eyal: It’s an educational and creative program bringing together creative people to work to together to know Israel by photographing and touring the country. We look at social problems in the cities of the development towns in the South, Bedouins, Arabs. It’s not a tourist program. It’s real work.

Yael: People learn from the landscape. We look at it and it looks at us. What is hidden and exposed. That is really studying a place. It’s not just mountains and plants. Its children, people, movements, television…

Zeek: What does the program look like?

Zeek: What does the program look like?

Yael: Every week we have a different subject. We are located in two kibbutzim, one in the North and one in the South, and we travel to sites, working in the field.

Zeek: It sounds like this program goes against the grain by calling an artist a social worker, but also against the grain of what the Jewish world wants to do with Israel. If the Israeli myth is cracking, what does it mean to be exposing the problems? That’s not the standard Zionist message is it?

Yael: If you go to the Baba Sali’s grave in Netivot and listen to the stories and narratives of the people there and then you go to the grave of Ben Gurion and listen to his narratives and his dreams, you ask what happened to the Ashkenazi who came from Europe or the North African. They met each other here. These are real Zionist stories that should be told and heard. Artists need conflict and this program wants to expose conflicts. You confront things outside of yourself that also teach you something about yourself. This complexity brings us to the question of the relevance of making art today.

Zeek: How how long is the program?

Eyal: 15-20 people for 5 months. They don’t have to be professionals. The program is open so that everyone can learn from where they are. There are three courses: photography; video; and social art.

Zeek: What’s social art?

Eyal: Trying to learn collaboration with other people. There are very few schools that teach in this way. How does an artist related to a community? How can you come to people and have them tell you about their lives? It’s a unique point of view to be involved in social life and not to sit in the studio but to go out to people. How do they get by? What do they do? We organize meetings with all kind of artists. Theater, film, lectures. And different parts of Israeli society – settlers, Arabs, the widest range.

Yael: It’s a call for arts to come back to culture. Not exhibits in white rooms. For too long when people go to a museum the people have been expected to adjust themselves to the art. It is time for the art to adjust to the people.

I have been trying to find info like this.

Many thanks I ought say, impressed with your site. I will post this to my facebook wall.

olive oil is very very tasty if you put it in fried foods and you can taste it raw too.

before you buy some very expensive SEO Tools, always look for a review first before you invest on them.

Nice post. I discover something harder on distinct blogs everyday. Most commonly it is stimulating to learn content using their company writers and practice a little from their site. I’d choose to apply certain using the content on my own weblog regardless of whether you do not mind. Natually I’ll supply you with a link on your web blog. Thank you sharing.