Around and around: the ongoing debates over Eva HesseRegularly exhibited during her lifetime in the museums and galleries of New York and abroad, Eva Hesse is still considered one of the major international artists of the late 20th century. Having studied at Yale University, she spent some time in Germany in the mid-1960s before returning to New York, where, between 1965 and 1970, she produced a body of drawing and sculpture that continues to exert an extraordinary influence on younger generations of artists. Her sense of herself as a female artist, choice of materials, Jewishness, and place in the artistic pantheon are, even today, hotly debated by art historians and critics. In discussions of her work, one key area of debate has been the extent to which her sculpture should be contrasted with Minimalist work of artists such as Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt. Though some scholars prefer to herald her as a proto-feminist artist at odds with Minimalists, others draw many parallels between her work and theirs, looking to their shared use of seriality, repetition, floor sculpture, and industrial materials. The technical and formal similarities are not the only reason to consider such links, Hesse had an extraordinary range of contacts in the New York art world, and knew, personally and professionally, figures such as Andre and LeWitt as well as Mel Bochner, Robert Smithson, and Richard Serra. Some feminist approaches to Hesse look in detail at the work of 1964-66 such as Ringaround Arosie, included in the exhibition at the Jewish Museum. To what extent can one read these works in terms of bodily imagery? Breast forms, phallic forms, and womb like forms do appear in Hesse’s work, but never in the explicit manner of later 1970s feminists. Different psychoanalytic theories have been mobilised to think through these aspects of Hesse’s work, particularly Melanie Klein’s writings on the “part object.” Some art historians have also considered why these forms drop out of Hesse’s late sculpture, and in what way the physical body and a sense of the bodily might be in play in the late works without the body being directly represented. Another area of debate concerns the material deterioration of Hesse’s work. She was one of the first artists to use latex and fibreglass, and many of her works in these media have become discoloured and brittle over time. As a result of this decay, some of her most important pieces can no longer be shown. Hesse knew, to some extent, about the durability of her materials, but there is no way of telling whether she would have remade certain works had she survived to see this deterioration. Must one read the frailty of her work as connected to her long-term illness and early death? Should curators and conservators re-fabricate certain works whilst Hesse’s studio assistants (who made the work alongside her) are still alive? What authority should those studio assistants have over an art work in which they were complicit but not in charge? Increasingly, scholars are seeking to ask how Hesse’s Jewish background might affect the way we can think about her work. Hesse was born in 1936 in Hamburg, leaving Germany on the Kindertransport to Amsterdam before eventually arriving in New York. Are Hesse’s works haunted by the Holocaust, and did her experience of displacement affect her art practice? In thinking through these and other questions, historians have tended to look at the implications of her return to Germany as a young artist, and to comments she made near the end of her life in which she related Carl Andre’s work to the floors of concentration camp showers. In the current exhibition at the Jewish Museum, the curators have for the first time displayed documents relating to her birth in Nazi Germany, and the Tagebucher (diaristic photo-albums) her father made for her in which her flight from Germany and arrival in New York is recorded. The curators display both her work and this documentary evidence, being quite clear to separate the biographical material from the galleries in which her work is shown. They acknowledge the necessity and difficulty of relating life to art, leaving the question of the relationship up for debate. Mark Godfrey is Lecturer in the History and Theory of Art at University College London, his essay in the catalogue for the exhibition discusses Hesse’s late hanging sculptures.

|

Is biography destiny? “Eva Hesse:Sculpture,” a starkly dramatic exhibition showing at the Jewish Museum through September 13, unabashedly claims that it is, as Hesse’s Jewish biography allows the curators to take her and her oeuvre and sculpt her into a Jewish artist. The inclusion of a vast amount of family memorabilia, much of it documenting a traditional Jewish life into adulthood, constitutes both a large part of the exhibition and the justification for showing works at the Jewish museum that have neither Jewish subject nor obvious Jewish content.

Hesse died at the age of 34 in 1970, leaving behind diaries, photographs and interviews, and having just produced some of her most astonishing sculptural works during the period in which she was battling brain cancer. The thoughts and words of the artist herself provide the clues as to how, and why, she came to be an innovative sculptor of innovative materials and works that challenged conventional artistic norms. Her experiences – as Jew, immigrant, refugee, and survivor of family trauma – each in its own way affected Hesse’s world view and artistic goals. Hesse’s early exploration of new modes of sculptural expression through the use of mundane materials – latex and other rubber, surgical hose, fiberglass – whose resulting forms were deliberately unpredictable, is consonant with a persona developed out of as her sense of displacement. The narrative texts that accompany the exhibition emphasize the artist’s belief that “her art and her life were interconnected.”

Hesse was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1936, the second of two daughters of a middle class couple already feeling the effects of Nazi laws against the Jews. While her mother Ruth came from a non-religious family in Hameln, her father, Wilhelm (later William), a lawyer, was committed to the Orthodox way of life and was involved with the religious community in Hamburg. In 1938, as a result of the increased Nazi threat, Eva and her sister Helen were sent on a Kindertransport to Holland and lodged in a Catholic school. They were reunited with their parents after a relatively short, but nevertheless traumatic, separation. The family eventually made their way to New York City, settling in the growing German Jewish neighborhood of Washington Heights. Helen Hesse Charash, the artist’s sister, emphasizes in materials included in the exhibition how much their environment was suffused with Jewish ritual and community.

Hesse’s Jewishness is further emphasized in the detailed Tagebucher (diaristic photo-albums) William Hesse made for his daughters, which show the family’s observance of Jewish holidays and Eva’s attendance at afternoon Hebrew schools and at an Orthodox summer camp where this writer met her in the summer of 1949. I recall a dark-eyed melancholy girl whose sorrowful history made her seem to her bunk-mates like a fairy- tale victim, evil stepmother and all. (At that time and age, we were hardly knowledgeable about the extent of the Holocaust or about the traumas of those who managed to escape.) She was recognizably different from the rest of her carefree American-born bunk-mates, which could account for her early feelings of being an outsider.

As I followed her career during her lifetime and the exhibitions of her work since her death (including a major retrospective at the Tate Gallery in London in 2002) I was often provoked to think how little we really know our friends or can envision their potential. Of course, much of Hesse’s intense pain and stress was due to the difficulties encountered by many refugees. But in her case the trauma was aggravated by her mother Ruth’s manic-depressive illness that had already been manifest in Germany and was now intensified by their new living conditions and concern over the fate of family members left behind in Germany. Ultimately Ruth moved out of the home, the parents divorced, her father remarried, and soon after — shortly before Eva’s 10th birthday in January 1946 — her mother committed suicide. Eva Hesse’s own emotional stability would be a life-long concern. Despite emotional support from her father and early recognition of her talent by fellow artists and critics, Hesse suffered from panic attacks, insecurities over her abilities, anxieties over her status as a woman, woman artist and wife. In a lengthy 1970 interview with Cindy Nemser when she was already quite ill ( published in Art Talk), Hesse stated “…in my life – maybe because my life has been so traumatic, so absurd –there hasn’t been one normal, happy thing. I’m the easiest person to make happy and the easiest person to make sad because I’ve gone through so much.” Her personal depictions invite a psychoanalytic gloss, which critics and curators have been happy to provide.

To me, however, the attempts by art historians and critics to link Hesse’s art to her experience of the Holocaust seem stretched. Indeed, over and above her artistic production, Hesse’s written and verbal legacy affirms that she was concerned with intellectual and philosophical aspects of the act of creation — not with psychological catharsis. Nimser quotes Hesse as saying “when I work, it’s only the abstract qualities that I’m working with, which is to say the material, the form it’s going to take, the size, the scale, the positioning ….I don’t value the totality of the image on these abstract or esthetic points. For me it’s a total image that has to do with me and life.”

In 1961, Hesse spent 15 months in Germany with her husband, sculptor Tom Doyle (they would divorce as soon as they returned to New York). This was the turning point for Hesse. Doyle suggested to her that she try her hand at sculpture using the materials (“junk”) that were lying around in the unused factory that they were using as studios. Electrical cord, plaster, string, wire, steel – all became the elements of her works and eventually expanded to include rubber, fiberglass, plexiglass, and latex as well as other industrial materials. Hesse employed papier mâché techniques to create her sculptural pieces, all of which had specific placement in space in the artist’s mind. She was also rather obsessive about titles and purchased a thesaurus to play with conceptual words: “Accession”, “Accretion”, “Repetition”, “Schema”, “Sequel” “Connection” “Several”, “Compass” hint at Hesse’s interest in movement, change, and ephemerality.

In 1961, Hesse spent 15 months in Germany with her husband, sculptor Tom Doyle (they would divorce as soon as they returned to New York). This was the turning point for Hesse. Doyle suggested to her that she try her hand at sculpture using the materials (“junk”) that were lying around in the unused factory that they were using as studios. Electrical cord, plaster, string, wire, steel – all became the elements of her works and eventually expanded to include rubber, fiberglass, plexiglass, and latex as well as other industrial materials. Hesse employed papier mâché techniques to create her sculptural pieces, all of which had specific placement in space in the artist’s mind. She was also rather obsessive about titles and purchased a thesaurus to play with conceptual words: “Accession”, “Accretion”, “Repetition”, “Schema”, “Sequel” “Connection” “Several”, “Compass” hint at Hesse’s interest in movement, change, and ephemerality.

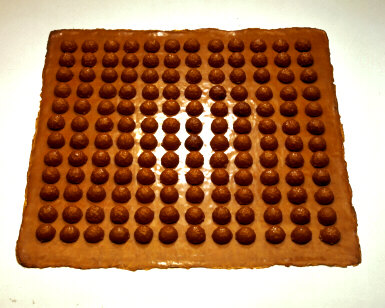

Each of the works in the exhibition demonstrates different aspects of the artist’s interests in materials. “Ringaround Arosie,” an early piece, uses raised forms of papier-maché wound cloth-covered electrical wire. “Accretion” consists of fifty tubes made of fiberglass and coated in resin. A complicated wrapping of paper tubes that are propped against a wall manage to seem both identical and individualized at the same time. “Schema” (shown here) is composed of 144 Spalding rubber balls covered in latex on a grid that relates to a rigid minimalist idiom. “Sequel” breaks the mold by giving the arrangement a randomness. At one point Hesse decided to hang her sculptures from the ceiling, as opposed to those deliberately grounded to emphasize their gravitational aspect.

Hesse’s statements at the time of her 1968 landmark exhibition entitled Chain Polymers (both latex and fiberglass are long-chain polymers – chemical compounds) at the Fischbach Gallery in New York sound almost Kabbalistic: “I would like the work to be non-work. This means that it would find its way beyond my preconceptions.” Or, “It is the unknown quantity from which and where I want to go.” Or, “In its simplistic stand it achieves its own identity.” Or “It is something, it is nothing.”

Despite the curatorial attempts to make some durable sense of her work, it is the random, chaotic aspects that dominate — along with the sense of fragility. Critics have described some of her pieces as organic and anthropomorphic, but Hesse’s achievement lies less in their recognizable elements than in the confrontation with abstract, non representational forms that exist for her in a non-present universe. Seeing Hesse’s work today does not startle; when it was first exhibited it certainly did.

Still, the viewer today can still feel a sense of discovery in Hesse’s work, of seeing in imperfect forms and shaped objects daring feats of creativity in the imaginative fabrication of materials, use of scale and space. The pieces convey complexity and ingenuity, inspiring a contemplative interaction with the works.

There is, however, an atmosphere of memorial tribute in this exhibition: an homage to the artist that is somewhat oppressive. Because of the emphasis on her tragically short life and her personal misfortunes, the exhibit is less of a critical assessment of her art than an episode of "Behind the Sculpture." As for Hesse’s Jewishness, the artistic impulse of creatio ex nihilo may or may not have been consciously Jewish, but the sculptures in the current exhibition, beautifully installed in the museum’s comparatively limited space, continue to captivate, perhaps because of her particular Jewish experience — or perhaps regardless of it.

Of course, if Hesse’s biography is not her destiny, then this is an exhibition at a Jewish museum that is devoid of Jewish artistic content. By way of response to this critique, I offer this excerpt from the 1976 catalogue The Jewish Experience in the Art of the 20th Century, an exhibit which coincided with the United States Bicentennial Celebration. In the prefatory remarks that could have referred to Eva Hesse, philanthropist Joy G. Ungerleider, the curator, wrote: “Ambiguity in defining the Jewish experience raises numerous possibilities…. Jewish artists have been drawn to the mainstream of 20th century art. Some will regard this participation as representing alienation from their Jewish heritage – others will regard it as an affirmation. The Jewish Museum believes that this is an historical phenomenon worthy of documentation.”

—————–

The exhibition will be at the Jewish Museum until September 17th. Exhibition Curators are Elizabeth Sussman and Fred Wasserman. The Jewish Museum is located at 1109 Fifth Avenue, corner 92nd Street in New York City. For the first time in its history the museum has Saturday hours (with no admission charge). For more information, please log onto www.thejewishmuseum.org or call 212 423-3200. To see the online gallery click here

Video izle kategori şişman mini etekli göt porno

video Sonunda Tatlı Sarışın Damla Mini Eteği. Mini etek ve kazak.

Mini kız-etek iki siyah dicks çalışır. • LIVE

SEX. kategori ⭐ en iyi 100.

Manfaat itu berasal dari berbagai kandungan yang ada dalam minyak kemiri, seperti

gliserida, asam linoleat, protein, vitamin B1, vitamin E.

Wow! that entry was basically pretty handy many thanks. “Quoting the act of repeating erroneously the words of another.” by Ambrose Gwinett Bierce..

That is some inspirational stuff. Never knew that opinions could be this varied. Do you still feel this way?

Thanks i love your article about Catholic Priests and Former Abortionist Confront Congress on Meaning of “Abortion” | Fr. Frank Pavone’s Blog

Every weekend i used to go to see this web site, for the reason that i wish

for enjoyment, for the reason that this this web page conations truly good funny stuff too.