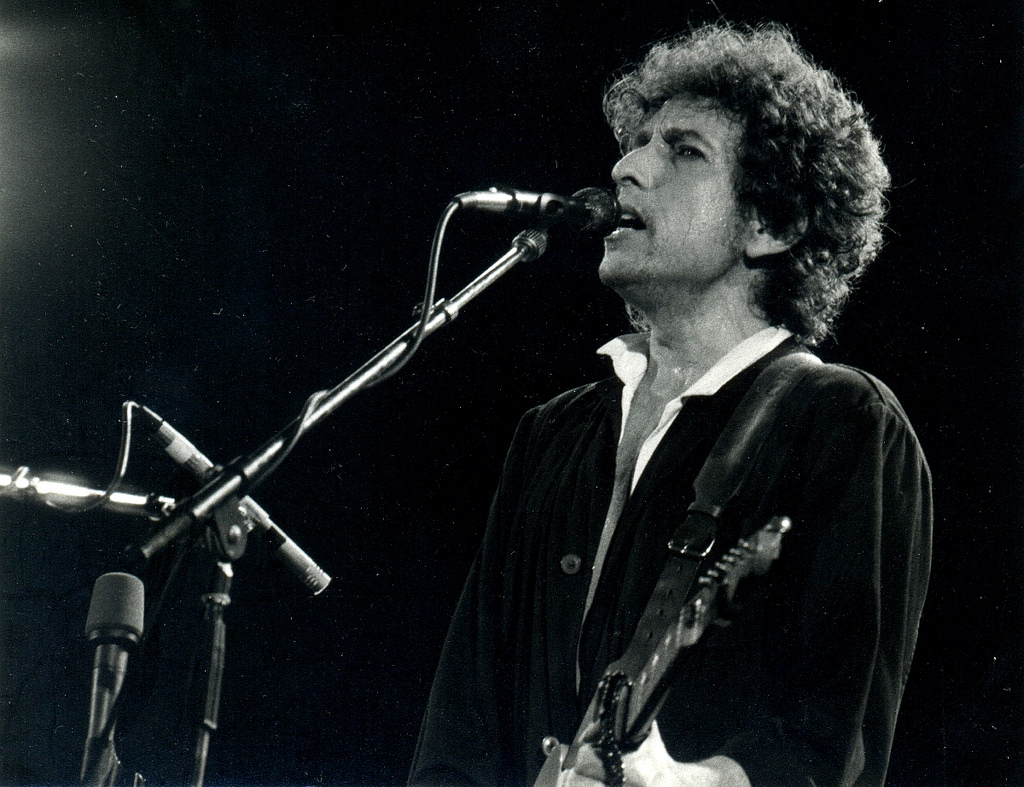

Bob Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman in 1941, has won the Nobel Prize in Literature, 2016. He now joins the ranks of American authors Toni Morrison, John Steinbeck, and Ernest Hemingway, also recipients of this honor. He is welcome into the fellowship of the Jewish Saul Bellow, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and Patrick Modiano (on his father’s side).

On Aish.com, Ilan Preskovsky offered Dylan an unqualified “Mazal tov,” and reminded readers that Bob was “born to a fairly observant Jewish family,” and “had a decidedly Jewish upbringing.” (Preskovsky seems to forgive Dylan for the unfortunate detour into evangelical Christianity.) This encomium, like all those in the Jewish press, mentions the simple and haunting “Forever Young” as having its origin in the Biblical priestly blessing. However, perhaps it is time to begin honoring Bob Dylan with the very Jewish virtue of age.

Dylan is now a member of a different and venerable club, of old Jewish men who have become iconic figures of cultural and personal longevity. (He should live to be a hundred and twenty!)

In a recent David Remnick profile in The New Yorker of Dylan’s almost landsman Leonard Cohen, another prophetic songwriter from just slightly farther north, Dylan analyzes the brilliance of his Canadian friend. Cohen, Dylan explains, is not principally a chronicler of depressing experiences, but an author of lyrical dialogues in the mode of Irving Berlin. Berlin, born Israel Beilin in 1888, by the time of his death at the age of 101, had written several of the greatest anthems of popular music by holding the listener’s attention, “as if he’s holding a conversation and telling you something, but him doing all the talking, but the listener keeps listening.” Dylan describes Cohen as engaged in the ongoing dialogue in which he himself has participated with listeners for more than fifty years, the same one featuring Berlin’s melancholy question, “What’ll I do with just a photograph/to tell my troubles to/When I’m alone/with only dreams of you/that won’t come true/What’ll I do?”

Then there is Ira Gershwin, (Israel Gershowitz, 1896-1983) whose brief partnership with his brother George ended with his sad poem to a musician who indeed, dying at the age of thirty-nine, was “forever young.” (“The Rockies may tumble/Gibraltar may crumble/they’re only made of clay/but, our love is here to stay”).

How about Yip Harburg (Isadore Hochberg, 1896-1981)? His meditation on the elusive nature of dreams, accompanied by the minor key notes of Harold Arlen, (Hyman Arluck), reflects the sadness of the Jewish immigrant experience as well as the human inability to ever reach the symbol that rewarded Noah after the flood, “Somewhere over the rainbow/skies are blue/and the dreams that you dare to dream/Really do come true.”

There are many Dylan lyrics which allude to Jewish experiences, from Abraham’s defiant challenge to God in “Highway 61 Revisited” to the perennial quest for freedom in “Blowin’ in the Wind,” a song which captured in some part the struggles of the Civil Rights movement in which he participated.

Yet somehow, “Forever Young,” a reassuring patriarchal prayer, encloses in its brief verses the true experience of a Jewish parent, or any parent, trying to extend wisdom to a child. Because we don’t want that child, or grandchild, to stay “forever young.” We want him or her to eventually be old, stable, and secure.

We know that our child will pass through the bitterness of “Positively Fourth Street,” the chaos of “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” and the romanticism of “Boots of Spanish Leather.” Like Jacob climbing the ladder and attaining a new adult identity, we want him or her to know the truth, the light, and courage listed as essential in Dylan’s song.

Image: Xavier Badosa via Flickr