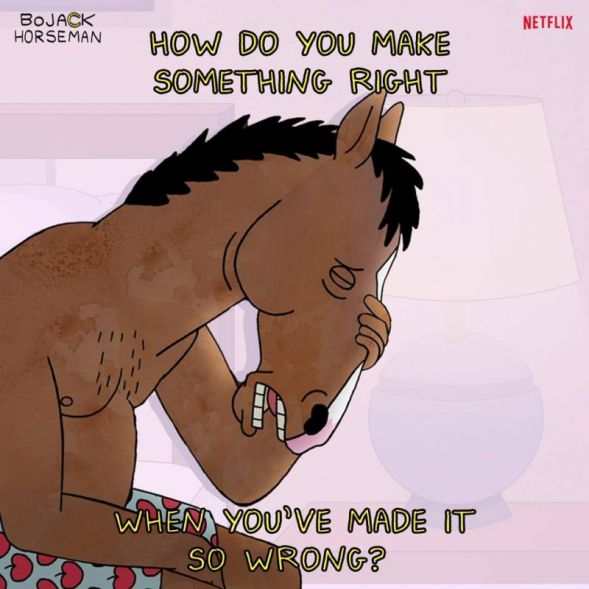

As Yom Kippur approaches, those of us who have difficulty addressing our flaws and making anew may have long ago built a layer of callus to the days of our year dedicated to repentance. Whether through cynicism or doubt, it seems that the best we can do is hold our breath and close our eyes, as the high holidays approach.

Thankfully, Netflix has sent us a savior. With the help of the Hasidic sage Sfat Emet and the Rambam, we can understand how even a (horse)man as hardened and unforgivable as BoJack Horseman may truly repent.

BoJack Horseman, after having spent the first three seasons watching its titular protagonist unsuccessfully attempt to find meaning in life, arrives in season four with several changes to the series (spoilers ahead). The most astonishing was BoJack’s severance from his closest companions: Todd and Princess Caroline. Somehow through all the years of disrespect, sabotage, and ungratefulness, Princess Caroline and Todd actually believed in BoJack. By forgiving him the countless times he’d hurt them, and always giving him another chance, they unknowingly perpetuated BoJack’s image of himself as a “good guy deep down.”

BoJack sees himself as the victim of cruel parents and an unfair world, thereby exempting him from responsibility over his actions. When he, say, sabotages Todd’s rock opera, his subsequent worries show his real problem. BoJack’s main concern is not the damage he has done to Todd, but the damage he may have done to his relationship with Todd. When Todd abstains from lashing out against BoJack, continuing to love him, BoJack interprets the silence to say that he is still a good person. Likewise, BoJack’s response to his heartbreak over Dianne shows him immediately dragging Princess Caroline back into a hopeless relationship, only to abandon ship the second she shows the slightest hint of vulnerability. Her constant reassurance that it’s not his fault, and that even though he’s an ass, he means well, allows BoJack to ignore the truth. The truth, is that BoJack is mean. He is selfish. BoJack is a shithead. Yet BoJack does not know that he is a shithead.

Leviticus 13 talks about skin conditions that may appear among Israelites, and the repercussions that follow its diagnoses as leprosy (temporary banishment from the community). The classical understanding of the story, brought to us by Bamidbar Raba (Naso 7), is that as a direct function of a multitude of possible sins, one is punished with the affliction, and banished into temporary isolation; as the Rambam explains, intentionally with an abject of public shaming.

The Sfat Emet turns this story on its head. He begins by offering us some ontological background information, writing that man was originally a being of pure light. Only after original sin were we covered with skin. But that skin has pores, which act as windows through which we are able to channel our inner light, by acts of kindness.

According to Sfat Emet, when we sin, our pores clog. Once the clogging has impeded on our link to the inner light, the vicious cycle persists, becoming even more difficult to reverse. Therefore, leprosy (tzaraat), with its white spots, is a solution to the greater issue: the hindrance of our inner light emission. The emergence of tzaraat is actually a gift, an opportunity for healing that calls for rejoice! Ultimately, everybody speaks ill; we all live with sin. Tzaraat come as a wake up call to provide us with the thing we lack most, awareness of our own misgivings— awareness which Bojack, for one, has lacked.

Recognition of sin, as Rambam explains, is the most fundamental step in repentance. This becomes incredibly difficult with others around. While support and love from family and friends is crucial, often their unwavering support and biased view can inhibit self-awareness. Their very presence may be enough to say, “I’m doing fine.” The Sfat Emet explains that this reality necessitates the next stage in the tzaraat cleansing process, isolation.

Bojack knew he was bad news. The rut he was in seemed so deep he was just about sure he would never escape. Yet he never stopped turning to his loved ones for assurance that he wasn’t all bad. As he continued to hurt those around him and subsequently fall deeper into depression, the one thing he could never admit to himself was that despite all his efforts, he was simply a bitter and unloved celebrity, with little in his life to give him pride. He was always the good guy, who as an unfortunate victim of circumstance, inevitably fucked things up. Perpetuating this pattern more than anything, was the lack of definitive rebuke.

That is until the end of season three. After almost three seasons of total jackassery, BoJack unwittingly turns away his most important pillars of support. He ruthlessly fires Princess Caroline. From a plea of desperation, BoJack then mistakenly unveils his betrayal of sleeping with Emily to Todd. Finally, culminating three seasons of suppressed anger and disappointment, it all comes out:

Todd: No, no! BoJack, just… stop. You are all the things that are wrong with you. It’s not the alcohol, or the drugs, or any of the shitty things that happened to you in your career, or when you were a kid, it’s you. Alright? It’s you. Fuck, man…

Desperate for anything to distract him, BoJack drags Sara Lynn out of recovery on a drug induced bender. Then in the most ripe moment possible, Sara Lynn, his last resort, his closest thing to family, dies in his arms. BoJack is alone.

In season four, Bojack strikes up a rather comical and symbiotic relationship with his fellow manic depressive neighbor. The climax then comes when his neighbor attempts to kill both of them while revealing that the source of his own depression was having directly caused his wife’s death. Merely escaping death, Bojack loses it. He can no longer deny his role in the tragedies of Sara Lynn’s life, he rushes inside and begins to panic. Finally he calls Dianne, the one person who has never had a feigned image of him, but has always loved him nonetheless. He tells her, “It’s beautiful here, and everything sucks.”

The reference is to Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 masterpiece, Slaughterhouse Five. The protagonist, Billy Pilgrim thinks up the aphorism “everything was beautiful, and nothing hurt” as a summation of his time spent as a survivor of the Dresden bombings and a POW in Nazi Germany. Billy Pilgrim, who has become unhinged in time, has the audacity to share that by experiencing his entire life simultaneously, he now understands that suffering is not real. Just as Billy Pilgrim jumps around time, oblivious and giddy, ignoring the horrid realities he sees, so does Bojack. Bojack has caused excruciating pain. Through a steady income of vices, both conspicuous and not, he’s avoided reality for fifty one years. Now, he’s finally landed, “It’s beautiful here, and everything sucks.”

Bojack has finally recognized that he has gotten everything he could possibly want, and that the fault for his misgivings and discontentment must lie within himself. The hardest part though is that he must take that step forward into his everyday life. His test comes in the most extreme fashion: Hollyhock, BoJack’s sister, shows up. The Old Bojack would have seen Hollyhock’s sudden appearance as an opportunity to finally find meaning and happiness in life. That prism itself though, would have turned Hollyhock into another pawn in the Bojack narrative. It would have limited his ability to actually appreciate her for who she is. The new disparate Bojack, discovers who Hollyhock is because he did not insist on using her as a means to an end for his own happiness.

In classic Bojack fashion, a drastic turn for the worse happens when Bojack’s mother poisons Hollyhock nearly to the point of death. The old Bojack would have dodged responsibility, blamed his mother, his past, his vices, and expressed concern mainly for his loss of a newfound relationship. He may have tried to fill the void with another goal. Or spiraled into a sequence of self loathing. Incredibly, enabled by the isolation and honest reflection— akin to that encouraged by the Sfat Emet— he doesn’t do any of those things; instead he worries about Hollyhock. Bojack “gets his shit together,” finds a way to help her, and fix the wrong. After affirming this and speaking earnestly with his newfound sister, Bojack earns his first positive moment in the series. An unfamiliar expression forms on his face; Bojack smiles.

Image via Facebook

good article, thanks a lot