In the aftermath of Trump’s election, there has been no shortage of topical, ultra-relevant stage productions. To name a few, this past year brought us The Public Theater’s controversial Julius Caeser, an off-Broadway production of 1984, a concert production of Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins, a limited engagement transfer of Angels in America, and, of course, the upcoming Mean Girls musical.

My question is, where is Parade?

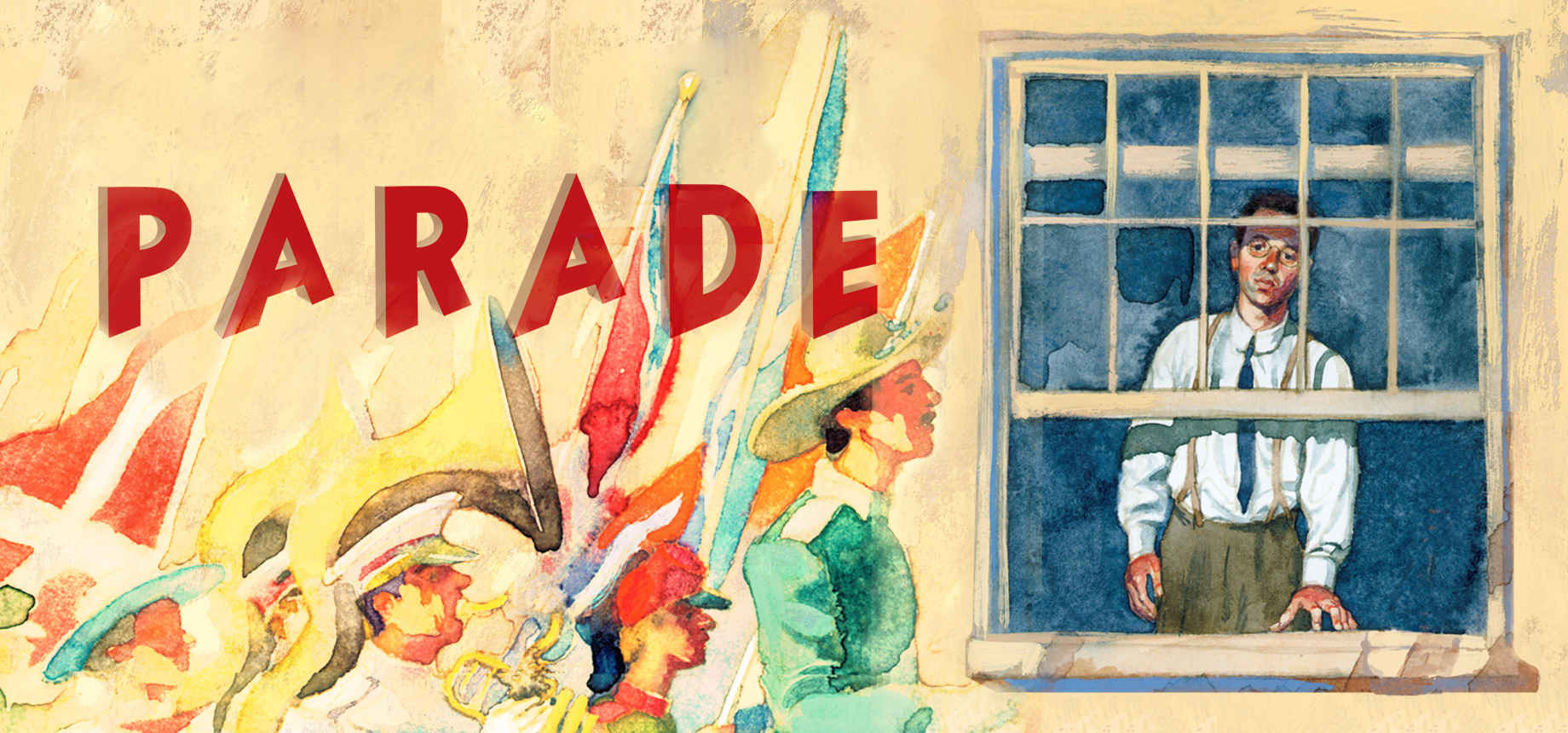

Parade is a 1998 musical about the hanging of Leo Frank, a Jewish man living in Georgia, accused in 1913 of killing a 13-year old girl. Although Leo Frank was originally sentenced to death, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment based on overwhelming evidence that he was wrongfully convicted. Before he could be cleared further, he was kidnapped from his jail cell and lynched.

Parade touches on all the pressure points of America in crisis: dark, xenophobic nationalism; boiling racial tensions and anti-semitism; the resentment between rural Southerners and urban Northerners; the dangers of fake news and mob mentality.

On top of that, it’s a masterpiece. Credit Alfred Uhry, the Atlanta-born Jewish book writer, and composer Jason Robert Brown (New York Jewish). Jewish theatre writers are common, but the hanging of Leo Frank is a significant piece of Jewish history—it inspired the founding of the Anti-Defamation League—so it’s especially important that it is rendered by Jews.

There was a special concert revival of the show in 2012, but that was a lifetime ago. Obama was president. White nationalist rallies were generally frowned upon. Conversations about Nazis didn’t end with smug centrist “Well, aren’t people who hate Nazis just as bad as real Nazis?”

The show opens with a rousing patriotic hymn sung by a young Confederate soldier. “Old Red Hills of Home” doesn’t work if there is any East Coast liberal elite judginess about what the Civil War was really about, and to his credit, Jason Robert Brown keeps it earnest. Form the soldier’s perspective, he is not fighting for slavery or hatred or love of violence. He is fighting for values, for “a way of life that’s pure/[For] the truth that must endure.” (You know, these values and purity were rooted in the belief that people could be property, but that’s for the audience to bring to the material.)

Flashforward to 1913. The soldier has lost his leg and the South has lost the war, but neither have lost their pride. Their fierce protectiveness for their way of life and their bitter hatred for the North have only intensified. Most of the city is excited to celebrate Confederate Memorial Day, except Leo Frank, a Jewish Brooklyn transplant. Four years prior, wife’s uncle offered him a great job running a pencil factory but, as Leo laments, “I should have known it pays so much because you have to move to Atlanta to do it.”

He remarks to his wife “Confederate Memorial Day is asinine. Why would anyone want to celebrate losing a war?” (Right?) His wife, Lucille, doesn’t share his attitude. She is Georgian born and raised, and proud of it. To Leo, Atlanta is “the land that time forgot.”

Leo’s song, “How Could I Call This Home?” highlights his wry Jewish humor and outsider status. “These people make no sense, I live in fear they’ll start a conversation,” he says. Even his connection to Judaism is strained: “These Jews are not like Jews/I thought that Jews were Jews but I was wrong.” His wife would prefer that he say “howdy, not shalom.”

From there, things move quickly: An young employee of the pencil factory, Mary Phagan, is found dead in the basement, Leo Frank is the immediate suspect, and a desperate reporter, Britt Craig, leaps on the story.

The city is out for blood. They want justice, and they want it fast. Suspicion falls on Leo and keeps piling up, regardless of whether it’s based on fact. As Craig points out, Leo is an educated Jew from Brooklyn, an easy target to villainize in Georgia. Craig deals in anti-Semitic caricatures: “Give him fangs, give him horns, give him scaly, hairy palms.” It sells papers, it gets clicks—what else matters?

At the trial, from a combination of false testimony and playing on the emotions of the white, Southern jury, Frank is sentenced to death. The city celebrates with yet another parade.

As Leo awaits his death, Lucille has no choice but to spread his story outside the city. Atlanta is divided on racial lines, with members of each group looking out for each other, and Lucille and Leo belong to neither. (There is an uncomfortable caveat to Parade: Historically, Jim Conley, an African-American man, was most likely Phagan’s murderer. The show’s writers attempt to balance his presumed guilt with the fear of violence the black citizens of Georgia lived under constantly, contrasted with the far rarer historical anecdotes of violence against Jews.)

Public pressure reaches Governor John M. Slaton and he decides to re-examine Leo’s case. With Lucille’s help, they gather enough evidence to have Leo’s sentence commuted. Leo and Lucille hope he will eventually be exonerated.

But the public outcry, the new evidence, the redacted testimony, the judicial system—none of that matters to the city and surrounding neighborhoods. They are convinced that a Jewish outsider assaulted and murdered an innocent child. In the middle of the night, a mob of angry men break into Leo’s cell, kidnap him, and lynch him.

After Leo’s murder, Lucille chooses to stay in Georgia, which she still considers her home. When Confederate Memorial Day rolls around again, Lucille watches the parade. The show is mostly devoid of reprises, but the first number, “Old Red Hills of Home” returns as the finale. The lyrics don’t change, but they are cast in a new harrowing light. What, exactly, do these proud citizens stand for? What is the “way of life that’s pure?” What does a parade really represent? The final image of Confederate flags flying across the stage in a militaristic parade evokes a chill today that they wouldn’t have five years ago, let alone in 1998 when the show opened on Broadway.

Parade is not a crowd-pleaser. In fact, it closed after 84 performances despite good reviews and nine Tony nominations (it won two: Best Book and Best Score). It’s a bleak musical, but it’s derived from bleak history, and we’re living through a bleak present. (And as for casting, Jewish two-time Tony nominee Brandon Uranowitz really wants to play Leo Frank.)

There’s never been a better time to bring Parade back in any capacity, and we can only hope that it is never more relevant than it is now.

Image via Musical Theatre International

Assistir o Filme The Magdalene Sisters Online Legendado Lançado Duração 2h 42

atas Orçamento US$ milhões Renda US$.

Nistabolje 8 Adet Hurç Yorgan Hurcu 100x50x40 Cm Büyük Mega Boy

(13) 199,99 TL. HIZLI TESLİMAT. renklibebek Hurç 5’li Büyük Boy Gri Renk Baza Altı Tela Hurç ~ Ölçü:

5 X (62x46x22) (102) 141,31 TL. HIZLI TESLİMAT.

Serstil Mega Boy Baza Altı Antrasit Hurç 74 X 46 X 22 Cm.

Yanıt: kardeşim kapalı ama aaçılmak istiyor. Evvela sizlere sabır,

kardeşinize de göz aydınlığı diliyorum. Belki haddime değil böyle

bir konuda söz söylemek. Hatalarımdan ötürü.

Check out featured izmirli garden can be show porn videos on xHamster.

Watch all featured izmirli garden can be show XXX vids right now.

Gece kulübü, lezbiyen şerit oyun bedavaseks. Işığı

kapatın. Mona Lee tam vücut külotlu çorap drTuber.

05:54. Tüylü Lezbi BVR Satılık Oyuncak Oyun xHamster.

17:16. Kadınlar dışarı inatçı elde için buradalar SunPorno.

05:14. striptiz. Porn Channel: VideoSection. Favorilere git Rapor Et.

Setilstearil alkol cilde yumuşatıcı bir his verir ve yağ

içinde su emülsiyonlarında, su içinde yağ emülsiyonlarında ve susuz formülasyonlarda kullanılabilir.

Setilstearil alkol, saç kremi ve diğer saç ürünlerinde yaygın olarak

kullanılır. Setilstearil alkol (CSA).