When Mikhal Gilmore of Rolling Stone asked Bob Dylan about the significance of the release of his album Love and Theft on September 11, 2001, Dylan offered a metaphor capturing the essence of his artistic vision:

When Mikhal Gilmore of Rolling Stone asked Bob Dylan about the significance of the release of his album Love and Theft on September 11, 2001, Dylan offered a metaphor capturing the essence of his artistic vision:

I mean, you’re talking to a person that feels like he’s walking around in the ruins of Pompeii all the time. It’s always been that way for one reason or another.

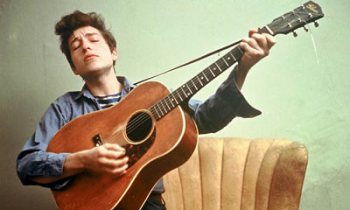

Ever since he trundled into New York City at the age of twenty in 1961 – in the words of early patron and former partner Joan Baez “he burst on the scene already a legend, the unwashed phenomenon, the original vagabond” – and thirty years after he declared unequivocally “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” people still look to Bob Dylan to make sense of what does not make sense in the world. Now, amazingly, with the August 2006 release of Modern Times, Dylan at age sixty-five becomes the oldest living artist ever to top international record charts.

The key to understanding the longevity of Bob Dylan’s creative output and public appeal lies in the self-reflection he offered to Rolling Stone. Dylan’s allusion to Pompeii is fitting both because his technique of composition dates back to the artistry of sages, poets, and rhetors of the classical world and because the stories he tells are grounded in committed, creative remembering of faces, names, stories, phrases, and melodies otherwise frozen in the past. In considering Dylan’s pattern of awakening the artifacts of the past so that they might be carried into the future through art, an insight Walter Benjamin once raised about the appeal of great novels applies. Great novels, Benjamin said, offer “the hope of warming the shivering life [of readers] with a death we read about.” As an artist immersed in translating societal and personal loss, Dylan masters contemporary expressions of ancient systems of memory that transform even the most powerful and painful truths into generative and life-affirming lyric verse that people can truly hear. Despite the little daily deaths of loss of meaning or the gaping losses generated by events like 9-11, great art and great artists suggest maps for turning forsakenness into resignation and transcendence. To understand Dylan’s creative process is to reveal strategies for living righteously amidst empires, East and West, that are continually flattening memory and misinterpreting the opportunities of mortality as an excuse for promoting a culture of death.

Pompeii Revisited

Bob Dylan has often been compared to Homer – and Shakespeare and Milton and Dante and Keats and Whitman and Rimbaud too. But if one wants to flirt with a juxtaposition of Dylan to a poet of the past, particularly a poet from the classical world, Simonides is the most fertile pairing, exemplifying work memorializing and renewing the cultural rubble that the mainstreams of their societies would otherwise leave behind.

In a well-traveled story related by the Roman rhetors Cicero and Quintilian, the lyric poet Simonides (ca. 556-469 BC) had been invited to chant at a large banquet in honor of the wealthy nobleman Scopas. When Simonides concluded his poem – and after Scopas had told him that he would pay him only half of his fee – a messenger informed Simonides that two young men were waiting for him at the door. Simonides went outside, but there was no one there. With the poet still absent from the banquet hall, the roof collapsed, killing Scopas and all of his guests. As friends and relatives of the dead arrived to collect the bodies of their loved ones, they found them so disfigured that they could not identify who was who. Simonides, however, recalled the place where each of Scopas’ guests had been seated at the table and identified them all.

Very much by accident – an actual, horrible accident – Simonides had discovered the “method of loci,” a core memory technique of the ancient world, which uses exacting visualization of specific locales as templates for storing and remembering information. Just as Simonides had instinctively used the fixed tableau of a banquet table to place and recall the names and faces of the scores of guests at Scopas’ feast, so many ancients employing the method of loci “placed” or “stored” information (for example, the words of a speech) piece by piece in different locations throughout a meticulously crafted, unique, and unchanging background. The memory tableau might be a perfectly reimagined banquet table – as was the case with Simonides – or the rooms of a house, a main street, or any other stable and intimately known space. When a person required the knowledge stored within the tableau he or she would take a “stroll” through his or her mind to “re-collect” and “re-member” the words.

While the description of Simonides’ “discovery” is almost certainly apocryphal, serving as a narrative mode for teaching a system developed by many people over a long period of time, it suggests a compelling and singular role for poets: that they have powerful tools of memory and communication to make sense of the past in a way that allows those still standing to move forward, particularly in times of communal crisis.

As echoed in his statement to Mikhal Gilmore, the central narrative figure of Dylan’s body of work has always been a solitary person on a life-stroll through the United States of Pompeii, his songs representing glimpses into the  stages of a journey through what was has been upended, what is changing, and what has been damaged. Yet unlike Simonides, the memory system Dylan employs offers shifting tableaux for memory – songs carried in a rotating backdrop of archetypal lyrical vessels such as the proverbial traveler’s road, a ship, a train, a dream, a horse, or a woman’s face. The content buried and drifting and tripping in and around these tableaux consists of the flotsam and jetsam of the lyrical vocabulary of traditional post-Civil War folk and blues, country and art songs from the heyday of recorded music leading up to the Depression and beyond it, cinema from silent to noir to Western, literature and poetry, old radio and television shows, the Bible, and layers of mythology. The raw material of Dylan’s songs is an exhaustive library of popular culture spilling forth from the shelves of collective memory onto the poet’s writing table for filing; pieces of a cultural puzzle configured and reconfigured, each song a “re-membering” encounter with the popular canon in which elements of a hero’s quest unfold. Dylan’s narrators’ rambling with a supporting cast of archetypal friends including Leadbelly and Charley Patton and Neil Young (the Bards), Mona Lisa and Madonna (the Lovers), Jesse James and Frankie Lee and Judas Priest (the Outlaws), Jesus (the Savior), Lenny Bruce and Tweedle Dumb and Tweedle Dee (the Jesters), and Captain Ahab and the Vice President (the Madmen) epitomizes the breadth of the raw cultural material upon which he calls.

stages of a journey through what was has been upended, what is changing, and what has been damaged. Yet unlike Simonides, the memory system Dylan employs offers shifting tableaux for memory – songs carried in a rotating backdrop of archetypal lyrical vessels such as the proverbial traveler’s road, a ship, a train, a dream, a horse, or a woman’s face. The content buried and drifting and tripping in and around these tableaux consists of the flotsam and jetsam of the lyrical vocabulary of traditional post-Civil War folk and blues, country and art songs from the heyday of recorded music leading up to the Depression and beyond it, cinema from silent to noir to Western, literature and poetry, old radio and television shows, the Bible, and layers of mythology. The raw material of Dylan’s songs is an exhaustive library of popular culture spilling forth from the shelves of collective memory onto the poet’s writing table for filing; pieces of a cultural puzzle configured and reconfigured, each song a “re-membering” encounter with the popular canon in which elements of a hero’s quest unfold. Dylan’s narrators’ rambling with a supporting cast of archetypal friends including Leadbelly and Charley Patton and Neil Young (the Bards), Mona Lisa and Madonna (the Lovers), Jesse James and Frankie Lee and Judas Priest (the Outlaws), Jesus (the Savior), Lenny Bruce and Tweedle Dumb and Tweedle Dee (the Jesters), and Captain Ahab and the Vice President (the Madmen) epitomizes the breadth of the raw cultural material upon which he calls.

The allusions to figures and texts in the landscape in which Dylan’s heroes seek adventure directly reflect the fluid, and heavily referential (as the title of “Love and Theft” implied) way that their creator composes music. “Well, you have to understand that I’m not a melodist,” Dylan said to Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times in 2004:

My songs are either based on old Protestant hymns or Carter Family songs or variations of the blues form. What happens is, I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head. That’s the way I meditate. A lot of people will look at a crack on the wall and meditate, or count sheep or angels or money or something, and it’s a proven fact that it’ll help them relax. I don’t meditate on any of that stuff. I meditate on a song. I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” for instance, in my head constantly – while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to a song in my head. At a certain point, some words will change and I’ll start writing a song.

Dylan’s practice of repetition and “meditation” leading to new work is familiar to any committed musician, the jamming and wood shedding of repeating scales and riffs, a familiar rhythmic phrase, or a favorite song that ultimately bends itself into a melody that is called “new,” even if its creative genetic code can be traced back to the original, older form from which it slowly emerged. Though this repetitive practice takes place in garages from Olympia to Boston and in jazz clubs and in the locked rooms of teenagers everywhere, Dylan is also describing an art of composition used by bards for thousands of years.

One of the most compelling studies of the art of repetitive, formulaic, meditative musical-poetic composition appears in Albert Lord’s The Singer of Tales (1960), an attempt to explain how it was possible that Homeric epics – some of which are well over 10,000 lines long – could have been memorized and performed orally by the composers and bards of ancient Greece. Lord maintains that singers, performers, composers, or poets in traditional cultures create an original though inherently formulaic lyric every time they perform. They do not repeat a text verbatim, having memorized it “word for word.” Rather, each performance is comprised of a performer’s reworking a shared body of modular, traditional formulae within deep structures of action and narrative common to his or her culture. Think of how the basic narrative of a story like Little Red Riding Hood exists across scores of cultural milieu. A person well-versed in fairytales, even if he or she has not heard a particular version of a fairytale before, can quickly fill in the details of a new version within the genre because a prototype already exists deep within him or her. While the names and places and emphases of the story change based on the locale of the storyteller, its “Little Red Rising Hoodedness” stays the same. It is the strength of the skills of the storyteller that make a story great or mediocre, but a stories’ essence carries through regardless.

Recall the old joke of a man visiting a monastery where the monks know each other’s shticks so well that they just tell each other the numbers assigned to the jokes rather than telling the jokes themselves. After a few weeks watching the monks fall down with laughter whenever they hear the numbers “43” and “5” and “16,” the man stands up before the group, takes a deep breath, and loudly says “20.” The room is silent. No one laughs. Later, the man asks one of the monks what he has done wrong, “It’s all in the way you tell it,” the monk says.

Hence the Iliad and the Odyssey follow predictable epic narrative patterns and are full of stock characters and repeated epithets like “rosy-fingered Dawn” and “grey-eyed Athena” that serve as signposts, basic riffs of the repertoire to help the bard stay within the traditional form. Having grasped both the deep narrative structure and the catch phrases and formulae of the genre after years of listening to masters, a bard does not recite a rote text from memory. Rather, the bard activates his ability to access all he has heard recited before him, the “performance notes” gathered over years, laid out in various orders in a Simonidian tableau in his head, creating his own, traditionally grounded, but original performance as he sings and plays. The more he listens to other bards, the tighter his system of memory, and the more he practices, the richer his own expression becomes.

====

By obsessive, attentive, meditative listening and repeating, Dylan has gorged himself on the deep structure of the music of the Carter Family and Robert Johnson, as well as the sonnets of Shakespeare and the poetry of Rimbaud, the phrases and personae of James Dean and James Dillon, and being the very greedy listener that he has always been, he has gorged himself on just about every other form of cultural content as well. Throughout this process he  has stored this material, meditating upon it and reworking it so that “[a]t a certain point, some words will change and I’ll start writing a song.” The result – musically, lyrically, and thematically – is a reworking of a memorial of inherited content placed upon the tableau of a song.

has stored this material, meditating upon it and reworking it so that “[a]t a certain point, some words will change and I’ll start writing a song.” The result – musically, lyrically, and thematically – is a reworking of a memorial of inherited content placed upon the tableau of a song.

Dylan’s work is full of examples of this creative model. Christopher Ricks and others note how “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” comes out of the deep structure of the Scottish ballad “Lord Randal,” itself part of a particular song pattern and type reaching back hundreds of years. The traditional ballad says:

O where have you been, Lord Randal, my son? O where have you been, my bonny young man? I’ve been with my sweetheart, mother make my bed soon For I’m sick to the heart and I fain would lie down.

And what did she give you, Lord Randal, my son? And what did she give you, my bonny young man? Eels boiled in brew, mother make my bed soon For I’m sick to the heart and I fain would lie down.

What’s become of your bloodhounds, Lord Randal, my son? What’s become of your bloodhounds, my bonny young man? O they swelled and died, mother make my bed soon For I’m sick to the heart and I fain would lie down…

Dylan says:

Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son? Oh, where have you been, my darling young one? I’ve stumbled on the side of twelve misty mountains, I’ve walked and I’ve crawled on six crooked highways, I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests…

Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son? Oh, what did you see, my darling young one? I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it…

And what did you hear, my blue-eyed son? And what did you hear, my darling young one? I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’, Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world…

Ricks traces parallels, allusions, interpretations, and plain old playfulness between Dylan and scores of texts of the Western canon – from the Bible to Yeats. Jenny Ledeen, a marvelous character who travels the Dylan circuit in the summertime with a trunk load of copies of her book Prophecy in the Christian Era, cites meditative parallels between Dante and Dylan and Dylan and the Bible.

Or consider the obvious example of Modern Times’ “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” – its words, and music, and tempo sliding directly out of the deep structure of the original “Rollin’ and Tumblin'” performed most famously by Muddy Waters, who himself likely crafted a version of the song from blues idioms and forms already traveling in America for generations before they coalesced in the performance of a master singer and storyteller at a dive on the South Side of Chicago. Examples of Dylan’s practice of repeating “old” material in order to produce “new” material abound because this is exactly how Dylan as a traditionally grounded poet and musician works.

Commenting on the apparent overlap of phrases from Modern Times with the 19th century works of the previously little known poet Henry Timrod, Suzanne Vega misunderstood Dylan’s art in recent piece in the New York Times: It’s modern to use history as a kind of closet in which we can rummage around, pull influences from different eras, and make them into collages or pastiches.

Actually, it is modern to think that composition and imagination must represent something “new,” that “new” is better than “old,” that creativity grounded in repetition of inherited work is less original than “modern” work that an artist claims to have generated from his or her mind alone.

Return to Sender: “Desolation Row”

“Desolation Row” is one of the finest examples of Dylan’s use of inherited content reworked boldly by a poet attempting to make sense of a world gone wrong. Step right up and see science, legend, sacred text, show business, and literature circa 1965. See Cinderella, Bette Davis, Romeo, Cain and Abel, the Hunchback of Notre Dame, the Good Samaritan, Ophelia, Einstein, Robin Hood, Dr. Filth, the Phantom of the Opera, Casanova, Nero’s Neptune, the Titanic, and Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot “coming to the carnival tonight” on Desolation Row. (Click here for the full text of “Desolation Row”) Understood as a modern day use of the method of loci, the figures and things of the song emerge in a fixed geographical tableau, Desolation Row, a street whose emotional value gives it the “stickiness” classical teachers demanded for their students’ memory tableaux. In fact, childhood homes were favorite vessels for ancient memory technique, precisely because of the emotional pull they exerted on the memory in the very same way that childhood homes are often the stages of people’s dreams regardless of the dream’s apparent subject. Dylan’s narrator walks through a series of invented actions and poses dictated to himself, “re-membering,” i.e. putting together, cultural content from everywhere lest, as in the later masterpiece “Visions of Johanna,” he find that “his conscious explodes.” The stroll through memory, even if it is painful and bordering on absurd, is controlled by the choices of the rememberer.

Imagine the scenes of “Desolation Row” as a massive, baroque painting in a cavernous ivory hall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Louvre to gain a sense of how a poet takes possession of cultural content, majestically reworking and reorganizing material in order to create a memorial in the same way that the great painters populate the walls and ceilings of cathedrals with mythic tales containing their own revisions (and reservations) concerning the sacred canon. Just as Simonides grabs the social elite in the steel trap of his mind so that their faces might be preserved and dispersed when the time is right, the storyteller of “Desolation Row” slowly unravels his memory of faces when the world calls for it. But unlike Simonides, who claims to match the map of the people at the banquet precisely, Dylan employs an aggressive form of the method of loci, applying his own unique order to the raw material of history because this is the only way that tradition makes sense to him. He reorders the canon, history, and life itself so that he can survive them:

Yes, I received your letter yesterday (About the time the door knob broke) When you asked how I was doing Was that some kind of joke? All these people that you mention Yes, I know them, they’re quite lame I had to rearrange their faces And give them all another name Right now I can’t read too good Don’t send me no more letters no Not unless you mail them From Desolation Row

The letter he receives, perhaps the motivation to which the song as a whole responds, is an artifact from before the poetic salvation of the reimagined life of Desolation Row. In fact, this letter may as well have been written in another language altogether. It is unreadable, even offensive, because it ignores the fact that only reconstructed reality can preserve a sensitive soul from the cultural chaos of the “real world.” Dylan’s narrator sees the same faces as his pen pal, but each with “another name,” planted within his personal grid of desolation, grounded in the only terms that he can understand and accept.

In the same Mikhal Gilmore interview cited earlier, when Dylan was asked if he had a message for people about 9-11, he quoted the Rudyard Kipling poem “Gentle-Rankers”: “We have done with Hope and Honour, we are lost to Love and Truth/We are dropping down the ladder rung by rung/And the measure of our torment is the measure of our youth/God help us, for we knew the worst too young!” Dylan goes on to say: “If anything, my mind would go to young people at a time like this. That’s really the only way to put it.”

Just as Allen Ginsberg says in “Howl” – when Dylan was still just a little squirt wanting to be Little Richard – “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,” Dylan, at least in his mind, emerges from a generation where visionaries face loneliness and rejection from their society. Fittingly, the word “desolation” comes from the Latin word desolare, desolatum, meaning “to forsake.” Dylan literally sees his generation literally forsaken, frozen and dead, forcing him to create a new matrix for living. The result, as he sings in “Dirge,” is that he “paid the price of loneliness/but at least I’m out of debt.” Despite its dark side, the reward for carving new cultural paths can be freedom and lucidity that hints at transcendence and, based on Dylan’s immense popularity, might even draw others towards new paths as well.

Welcome to “Modern Times”

Mary Carruthers, author of The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture, describes to the phenomenon of “memorial” culture in the realm of medieval monks. From the time of Simonides through Cicero and onto the stages of the Church Fathers and medieval monastic culture – not the same monks telling the jokes above, perhaps – the method of loci served as a basis for sacred arts of meditation, prayer, translation, and manuscript production grounded in reworking and relearning classical, inherited texts. Ostensibly the monks created nothing “new” for generations. Yet as a form of “memorial” culture, monastic life was a constant process of resurrecting societies’ dearest inherited figures and symbols in study and art, “making present the voices of what is past, not to entomb either the past or the present, but to give them life together in a place common to both in memory.” According to Carruthers, a creative act in the ancient and medieval world was not an act of invention ex nihilo, but an act of re-imagination – the reconfiguring of texts and images preserved by the monks in the various tableaux of their memory so that they could form new sacred content out of inherited material otherwise lost and left for dead. While Bob Dylan is no monk, no saint, and no angel (particularly in light of a public religious quest that has included both Christian and Jewish orthodoxies as well as a healthy dose of anti-doctrinal fervor) he thrives not only on the content of religious stories and thinking, but also lives creatively through forms of memory and song craft derived from the ancients and utilized by the great religious traditions of the world for millennia. Bob Dylan – to whom so many look for insight during troubled times, demanding clear answers about what to do about the meaning of life but instead receiving cryptic, laconic messages leading to so much babble and frustration – has always been quite clear about how to make sense of the world. He relies on the bounty of the canons of music, art, literature, and legend to provide the inspirational colors with which to paint and repaint personal interpretations on the canvas tableaux of his choice. “Don’t follow leaders,” Dylan once said: reject leaders who lead you towards meaningless death even as you accept the infinite possibilities of your finite life. Reject damaging cultural norms precisely because you love culture so much. And if this calling for independent thought and living leaves you feeling forsaken and alone, remember that Bob Dylan also said: “‘I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours,’ I said that.”

In other words, turning inward towards a vision of a re-formed and re-membered world does not mean giving up hope on the world outside. Honest, disciplined, generous memory creates a generative tableau upon which the histories of neighborhoods and nations can be rearranged the way that they are supposed to be. Great art that gives history “another name” allows people to begin to share stories of a future that makes sense. If we listen and look carefully, we might even be able to hear and see these reimagined worlds well enough to make them real. And so, my friends, this is how rock and roll – and art and literature and theater and more – can still save the world. Thank you very much for the map, Mr. Dylan, and welcome to Modern Times.

I said that.

(Lead image credit: Don Hunstein)

Only wanna input on few general things, The website layout is perfect, the written content is rattling superb .