Although not quite at Fiddler on the Roof levels of ubiquity, The Dybbuk, or, Between Two Worlds, written at the turn of the century by ethnographer and playright S.Ansky, is one of the most widely known works of Yiddish theatre. The tale of thwarted lovers and demon possession continues to inspire re-stagings and re-imaginings. The latest is Looking Through Glass, a new modern-day adaptation by observant Jewish troupe 24/6 Theater, written by Ken Kaissar and directed by Yoni Oppenheim.

In the original play, Leah is the only daughter of a wealthy widower. Khanan is a poor Talmud scholar whose father died before his birth. They meet over a Shabbat meal the very night Khanan arrives in town to study at the beit midrash, and feel an instant connection—a connection that, unbeknowst to them, is the result of their fathers’ youthful promise that their unborn children would marry each other.

But motions are already in place to betroth Leah to another, much to the displeasure of her and Khanan. Khanan, already a Kabbalist, turns to increasingly fringe rituals to try and magically halt the engagement negotiations and acquire enough money to present himself as a suitable candidate. Eventually in desperation he calls on the Devil— and dies.

In Looking Through Glass, it is Leah’s mother is rather than father who is widowed, and Leah (Judy Ammar) has new dimension as an ER doctor. Leah and her beloved still meet on his first night in town—he is hanging out on her stoop in Brooklyn, reading a book of Kabbalah, as one presumably does in Brooklyn—but he is no Talmud student.

This Khanan— now named Jacob (David Hilfstein)— proudly tells Leah, her boyfriend, and her mother that he is a yeshiva drop-out who prefers to study now on his own. What’s more, he is a full-time “professional protestor” (not his term) from DC, passionate about protecting the rights of immigrants.

Leah’s mother and her boyfriend quickly out themselves as conservatives, asking Jacob why he wants to be an unemployed “agitator” protecting terrorists. (A line made a bit more nuanced by the fact that Vidal Loew, who plays the boyfriend, delivers it in a strong French accent.)

The boyfriend, Shmueli, is far more fleshed out in 24/6’s adaption than the nameless bridegroom in the original. Shmueli and Leah have known each other for years and have been dating for months by the time Jacob shows up. They are comfortable together, but no match for the chemistry the strangers have with one another.

In this version it is Leah, rather than a parent, who invites the stranger into their home for Shabbat dinner. And in this version, they don’t just stare at each other over the candle flames—after mom goes to bed, Jacob quizzes Leah about her level of attraction to him vs. Shmueli, then pulls her close and nuzzles her cheek.

In a talkback after the show, playwright Ken Kaisar said he wanted his adaption to empower Leah—“make her the driving force of the play, bring her to the fore.” But this is the first of several uncomfortable moments in which the script doesn’t seem to fully recognize the unbalanced power dynamic between her and Jacob.

In the modern era, it is not her father’s decision that forces Leah into a marriage, but societal pressures. She picks the stable Shmueli over the unknown passion represented by the stranger. (A choice that to me made a lot of sense, given Jacob’s grating enthusiasm for group meditation exercises—he’s #thatguy at your Shabbos table.)

But more damning is his reaction when running into Leah shortly after she has accepted Shmueli’s proposal. He yells at the woman he’s known for all of one weekend: “How could you expect me to be happy for you?” and then precedes to berate her for breaking his heart and removing all meaning from his life—a line that caused my female friend and I to turn to each other with eyebrows raised high in alarm.

If Leah was really a “driving force,” as Kaissar said, perhaps she would have pushed back a little more on this, but their fated attraction has its pull. She urges Jacob to find meaning in his life and forget her, and they tearfully part.

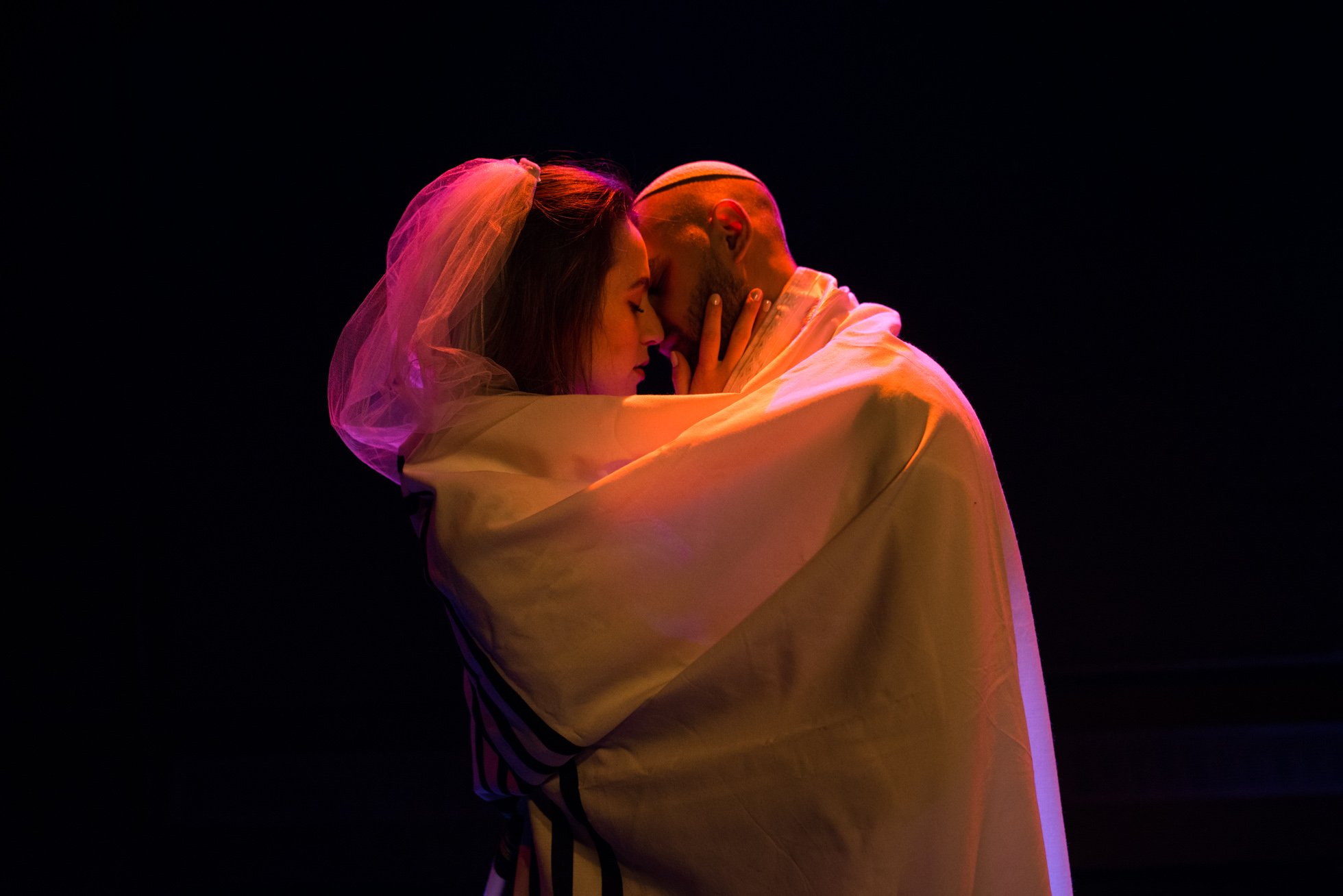

Like Khanan, Jacob now proceeds to die before his time, by suicide rather than the devil. And like Khanan, Jacob returns on Leah’s wedding night to possess his fated bride.

In The Dybbuk, this possession is invited by Leah—a powerful moment where, for the first time in the narrative she takes control of her own life. In Looking Through Glass it comes across as far less consensual (though Ammar gives a stunning performance, switching back and forth between her voice and that of the vengeful dybbuk).

In both iterations of this story, the exorcism efforts of the community fail, because ultimately Leah does not want to be saved.

The end of 24/6’s show reveals that, like in the original play, the fathers’ had made a pact of betrothal for their children. So how does the fact that Leah’s attraction to Jacob may not have been her own, but the machinations of a dead father? It’s never explored.

The show’s premise has a lot of promise, and brilliant, compelling performances from the two leads and from Avi Soroka (who plays the ghost of Sholem Ansky, as well as of Leah’s father, and is hard to take your eyes off of while he speaks). The staging at Jewel Box Theater in Manhattan was gorgeous, and it will be exciting to see what the cast brings to the next performance of the play, this Sunday at Ansche Chesed synagogue in Manhattan.

But it seems strange that a retelling that aims to delve into Leah’s inner life has so many moments that don’t fully explore her reactions—perhaps she doesn’t call out Jacob’s manipulations because of her Orthodox background, or because of her lack of a father figure, but we can only guess. If she’s still okay with the fact that she dies on her wedding day because of another man’s pact, then we need to know why.

It seems Leah has resisted capture once again.

24/6 will perform a reading of the play at Ansche Chesed in their chapel at 4pm this Sunday January 7th. Free and open to the public.

Photos by Paul Terrie

Viola aka elena mihaylova. 3 ay önce 53 izlenme.

Erkek kadin gures. 3 ay önce 59 izlenme. Turbanli potno izle.

2 hafta önce 13 izlenme. Bir cevap yazın Cevabı iptal etmek için tıklayın.

E-posta hesabınız yayımlanmayacak. Gerekli alanlar

ile işaretlenmişlerdir. İsim E-posta *.

Excellent. This article is just what I was hoping to find!

Excellent commentary on that subject. We appreciate your knowledge that you really to leave out with us!