There have always been cool Jews: Judah Maccabee, Bugsy Siegel, Lou Reed. But for one brief shining moment in the early Noughts, a curly-haired, comics-collecting, indie-listening ball of neuroses was the face postered on bedroom walls.

For fans of Marvel’s latest small screen offering, Runaways, it must have seemed like Chrismukkah came early when it was announced that showrunner Josh Schwartz would be one of the brains behind its leap from the comic pages. After all, who better to breathe life into smart, sarcastic, Jewish Gert (and her dinosaur sidekick, Old Lace) than the guy who created her spiritual ancestor Seth Cohen (and his toy horse sidekick, Captain Oats).

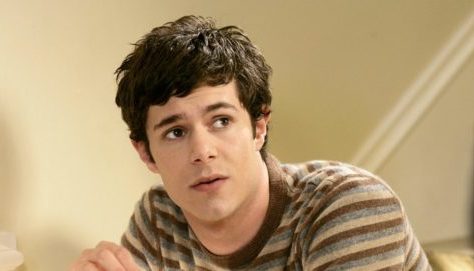

Seth Cohen was a different breed of teen idol, no less a romantic lead because he wasn’t muscled or athletic— or the fact that his childhood trauma stemmed from a friendless Bar Mitzvah party. But, of course, that was why The O.C. caught fire. Dipping into a genre that trends whitebread, Schwartz replaced the John Hughesian model of interchangeable suburbia and overspilling earnestness with his self-aware, highly located, unmistakably ethnic teen drama. The place, California’s wealthy and WASPy Newport Beach, would reign omnipresent and the people would be defined in relation to it. At the center of this world was a family who just didn’t quite fit in, the Cohens: exiled Bronx crusader Sandy and his blonde, blue-eyed wife Kirsten, their oddball son Seth (played, of course, by Adam Brody), and their adopted delinquent Ryan.

From the start, the Cohens’ difference to their neighbors was a source of comedic tension, and one of those many differences was that the Cohens were very, very Jewish. The show never tried to hide it and instead reveled in it as one of The O.C.’s trademarks. The first season introduced the concept of Chrismukkah, Seth’s attempt to wrangle nine nights of presents out of his blended family, to the show and to world at large, and each season would repeat the festival, escalating the drama exponentially— one Chrismukkah featured the invention of the “yamaclause”; another centered around Ryan learning a Torah portion for his Bar Mitzvah.

Unlike many Jewish characters, the Cohens didn’t simply become Jews on Christmas. Instead, their Jewishness saturated the show to the point of familiarity. One episode focuses on the visit of Sandy’s domineering matriarch, the Nana, as the Cohens scramble to put together a seder and Summer, Seth’s girlfriend, valiantly learns the Four Questions to impress his grandmother. A later storyline has Seth and Summer in a standoff over their engagement—Summer pursues conversion by grappling with a Torah scroll and learning to cook a brisket. And at a funeral, Seth, searching for the missing Summer, cracks “is she smoking the salmon herself?”

Of course, culturally, the Cohens were not the first gefilte fish out of water in the Golden State. Mark Harris, in his study of changing Hollywood in the 1960s, Pictures at a Revolution, highlights an epiphany reached by director Mike Nichols in the decades after he developed The Graduate. In Charles Webb’s book, Benjamin Braddock is another tall tanned sunburst of California WASP society. The movie version? Not quite. Says Nichols:

“It took me years before I got what I had been doing all along — that I had been turning Benjamin into a Jew. I didn’t get it until I saw this hilarious issue of MAD magazine after the movie came out, in which the caricature of Dustin says to the caricature of Elizabeth Wilson, ‘Mom, how come I’m Jewish and you and Dad aren’t?’ And I asked myself the same question, and the answer was fairly embarrassing and fairly obvious: Who was the Jew among the goyim? And who was forever a visitor in a strange land?”

The casting, unconscious or not, strengthens the tone of discomfort of the movie, as Ben is paraded, handled, and manipulated like a curiosity by his family and friends. In revisiting the scenario forty years later, The O.C. flips the script—the Cohens still can’t quite assimilate in their coastal California town, but this time, their neighbors are the outsiders, and the Cohens, with the audience in tow, become insiders. For instance, in one episode, Summer starts dating another boy to make Seth jealous. The boy, Danny, is constantly cracking jokes that send everyone into exaggerated hysterics. Seth, and later Sandy, are the only characters left stone-faced. (Sandy: “Gentiles. I love your mother more than words, but – not funny.”) And because the Cohens aren’t laughing, neither are we. By attuning the Cohens’ brand of wit as the show’s usual humor, the audience sides with the Jews on this one.

What the Cohens found cool, we found cool, and so The O.C. not only fashioned statements out of Seth’s love for The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay or Death Cab for Cutie, but also made the unglamorous—shuffleboard, bagels, showtunes, meatloaf—seem desirable. A Chrismukkah miracle, indeed.

daftar judi slot kakek petir deposit tanpa potongan

Great information! I??ve been looking for such as this for a little bit now. Thanks!