“I have finelly a grand son,” the Israeli writer Yoram Kaniuk wrote to me in an email three years ago. “wonderful at my age to be a new grabdfather. Life is shit but now I am awiming better then ever so there is hope

Yoram”

Over the course of the past several years, the notes I received from Kaniuk were often elliptical—lacking in standard punctuation and littered with misspellings. Part of me thinks those errors—and more than the mistakes, the “Life is shit” attitude—were intentional, to better allow him to project himself as a man possessed of an addled imagination and to wallow in the idea of the aggrieved writer, ignored by the Israeli (and worldwide) literary establishment in favor of younger, less controversial minds. I sometimes took it, perhaps unfairly and erroneously, as a pose designed to make me and others in similar relationships with Kaniuk write about him.

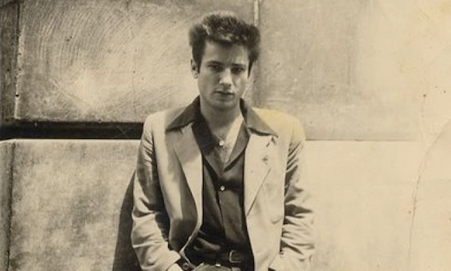

And there was so much to write about. Kaniuk was a member of the Palmach. He fought in the War of Independence. He helped shepherd Holocaust refugees away of Europe. He left Israel, lived in New York City and Paris, befriended the likes of Charlie Parker and Susan Sontag. He studied art and painted tiny pictures on matchboxes.

Having married a non-Jewish American, his daughters were not considered Jews in the country in which they were raised and so, more recently, he petitioned to change his legal status from Jew to no-religion, to match that of his grandson.

For the past several years, Kaniuk fought cancer, the illness that prevailed Saturday. And perhaps he had a point in his messages to me and others, that he did not receive quite the same recognition that peers like Aharon Appelfeld enjoyed. But it’s untrue to say he was unknown. His 32 books (including 17 novels) were translated into 25 languages and the Israeli establishment bestowed on him some if its greatest prizes. Messages for him on Facebook prove he was beloved by younger Israeli readers.

Kaniuk did not want platitudes—he did not want to be told “I liked your book”—an empty affirmation, to him. As he wrote me on another occasion, he was not “an American who stand before a painting and says: Ho, isn’t something! I really like it. and so on.”

I don’t claim a deep friendship with Kaniuk. I interviewed him once, and commissioned a few pieces of writing from him in 2006, when Israel seemed on the cusp of war with Lebanon. Those essays were—they are—like jazz, rhythmic with a feeling of impetuosity, filled with color and passion, invoking themes of aging and obsolescence and Israel’s precarious standing. They are balanced too by observations of occasional joy and whimsy. And there is nostalgia in them, as well.

When I last was in Israel, five years ago, I went to meet Kaniuk in his home in Tel Aviv. He was gracious and warm, as was his wife Miranda, and he offered to take me on my next visit to his favorite café. There, he’d introduce me to my future husband, he said. It was a suggestion rooted ever in hope.