The Senate has reached a bipartisan fiscal deal, but we at Jewcy are doing what we do best— watching TV so that you don’t have to, leaving you time to catch up on the debt ceiling news.

What’s with the Jews taking over TV? Last week a yarmulka graced the small screen, meant to be ignored, which we over at Jewcy took as ample evidence that Jews were ubiquitous enough to be invisible—the sign of having truly made it in Hollywood. But on this week’s episode of New Girl, further evidence for our thesis—that being in with the Jews or in on the Jewish joke is a new kind of standard—came to light.

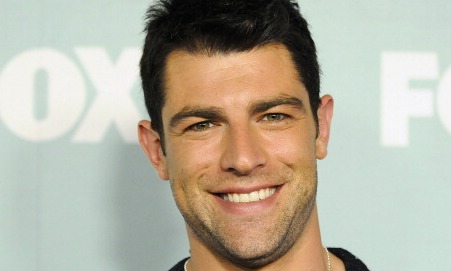

Tuesday night’s episode, “The Box,” could have been called “Jews and Money”, though the writers/producers/directors cleverly separated the two plot lines into “Jews” and “Money” and allowed Nick Miller (not a Jew) to handle the money end of things. But it’s the other plotline that interests us: after being discovered to be dating two women at once, Schmidt (Max Greenfield), the explicitly Jewish character, is worried that he isn’t a good person. We find him lying on a couch, earnestly running through a list of his symptoms (“I can’t sleep. My tweets have been extremely literal.”) to…camera pan out… his rabbi—ba-dum ching! While complaining to a rabbi like a therapist has become a staple of post-Coen brothers humor (“Were the girls Jewish?” the rabbi asks), what follows feels like new territory. The rabbi (Jon Lovitz) suggests that Schmidt seems “awfully concerned” with himself, and that he might try thinking of the needs of others. Lo and behold, on the street outside the synagogue, Schmidt saves a bike messenger from choking on a piece of gum.

“You saved my life, dude,” the bike messenger says, or something of that genre.

Schmidt, jubilant, stands up, and begins to recite, as Romy Zipken called it aptly, “the most boastful Shema you’ll ever hear.” And here’s the kicker: Schmidt gets the Shema all wrong. He mispronounces it— “Shema Yisroel Adonay EloCheiynu,” he proudly shouts, Jewing up one of the Jewiest utterances, second only to “Auf Mir Gesugt!” He also says it at the most inappropriate of all times. Shema is famously recited when someone is about to die, not when someone is saved, and surely, not when someone has just saved someone else. His pride, as Zipken points out, is another thing that makes the scene absurd. In other words, this is Shema camp, but astoundingly, the joke is on Schmidt. The writers (or perhaps this was Greenfield’s genius) must have assumed that their viewers would be canny to all the ways that Schmidt gets the Shema wrong. They are in on the joke; otherwise, the joke doesn’t work.

The next scene carries on the same vein. Schmidt encounters Nick in a bar, and greets him with the hilarious, “Nicholas! Gut Yontif! Are you well?” This greeting, like Schmidt’s Shema, is only funny if you are in the know. Even viewers who might not know what exactly Gut Yontif means, know that it is not an appropriate salutation on any old day in a bar. The writers are directing these jokes at a crowd who is in the know, who knows more about Jewish culture than Schmidt, the Jewish character. Schmidt importunes Nick to try giving “charity—or tzedakah as my people call it” and Nick begins to call tzedakah “tzaziki,” which is hilarious, again, because the word tzedakah is familiar enough to the viewers that they will hear the joke, recognize the infelicity. Imagine a similar joke being made with the word Kwanzaa. The resounding “ew” you just heard in your mind is the difference between having made it in American media and not having made it.

(Photo by Jason LaVeris/Getty)