When Jerome O’Malley calls you a “Fucking Yid” in the playground, that’s antisemitism. When your friend gets beaten up at a bus stop for wearing a kippah, that’s antisemitism. When your teacher – a reverend gentleman of the Episcopalian persuasion – refers to the high school students (some Jewish, some not) who are misbehaving in his class as “Hebrews” that’s also antisemitism.

When Jerome O’Malley calls you a “Fucking Yid” in the playground, that’s antisemitism. When your friend gets beaten up at a bus stop for wearing a kippah, that’s antisemitism. When your teacher – a reverend gentleman of the Episcopalian persuasion – refers to the high school students (some Jewish, some not) who are misbehaving in his class as “Hebrews” that’s also antisemitism.

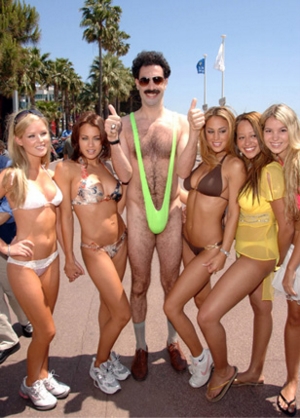

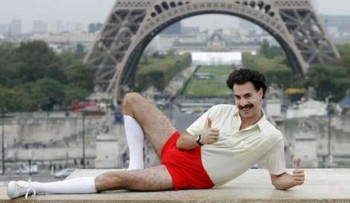

But is it antisemitic for the notoriously backward fictional Kazakh named Borat (played by the Jewish Sacha Baron Cohen — who is, by way of full disclosure, a good friend of mine) to expect Jews to be shape-shifting, money-demanding vermin in his new film Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan?

Even if the characters are explicitly rather than implicitly ridiculed for doing so (as in, for example, The Office) is it acceptable to tell an overtly racist joke (like the “black man’s cock” joke) three times in a thirty minute sitcom?

Is it acceptable if sterotypes are superficially exploded, as in Sarah Silverman’s song “I love you more…” from Jesus is Magic ? That song certainly examines stereotypes and clichés in a funny and uneasy way — that “Jews love money” and that “Asians are good at math” — but it also reinforces them. Stereotypes have an uneasy truth-status in culture and pop culture: We know they are not simply true, but usually we act as if they are. Is the repetition of stereotypes OK if it’s funny?

Silverman is also a master at violating taboos. In one bit, she compares how Jews and African Americans deal with controversial symbols. “Jewish people driving German cars, ” she says, is “the opposite of FUBU [the African-American ‘For Us By Us’ label]…it’s like take back the night.” But then she says, “maybe it’s like when black guys call each other”– the “N” word. The discomfort is palpable; white people aren’t supposed to say that word.

Given the questionable use of comedy to fight prejudice, why is there so much recourse to prejudice in comedy? On one level, it’s simply catharsis. Of the various possible responses to antisemitism, it’s the only one not haunted by childhood memories. Remember? Fighting back led to a bloody nose, calling the cops (or the teachers) to a reputation of tale-telling. So what do we do? Make fun of the racists, which works as a response, and also, hopefully, makes us popular. First we joke to each other, then with like-minded friends, and eventually – if we are funny enough – everyone is laughing at them and the culture has changed.

Consider Rob Schneider’s response to Mel Gibson’s drunken antisemitic outburst, which was to write a funny letter (well, it’s intended that way) explaining how he will never work with Gibson again and printing it as a paid advert in the Daily Variety. On one level this response succeeded, garnering attention, mocking the self-righteous tone of the ADL and similar prejudice cops, and even shaping a brief debate, while Ari Emmanuel’s blog and Gavin de Becker’s earnest letter as advert in The Hollywood Reporter largely failed to attract discussion. However, the fact that a superficial response to the outburst was more effective than any substantive debate may merely be illustrative how much easier it is to use humour and irony to deflect uncomfortable yet important issues. Schneider is not to blame for the limits of the debate. As a comedian his response was appropriate, but his success, however limited, just highlights the shortcomings of a view that thinks of comedy as redemptive, audiences as basically just, and antisemitism as a sad form of ignorance rather than a deeply rooted pathology. It’s a view that conveniently forgets the reactionary, racist, sexist, homophobic comedy that has had such a long history and still lives on today. As Paul Lewis points out in Cracking Up: American Humor in a Time of Conflict, irony and joke-making is not always a way of telling truth to power. In fact, it can be a conveniently slippery way of refusing to take responsibility for actions or utterances, a way of reinforcing the sorts of stereotypes that make the joker and his or her audience feel good at the expense of the butt of the joke. Lewis quotes Jay Leno being interviewed in the LA Weekly (Sept 17-24, 2004), saying that “you don’t change anybody’s mind with comedy. You just reinforce what they already believe.”

Today, cultural attitudes are changing locally and globally, and the acceptability of prejudice in general (think Danish cartoons and the Pope’s comments on Islam), and antisemitism in particular, is currently in a process of re-evaluation, at least in the English-speaking world. That antisemitism is again on the rise is indubitable, even as figures like Mel Gibson, Ken Livingstone, and Iranian President Ahmadinejad have been sharply criticized for comments that were either antisemitic or perceived as being so. Surely it is no coincidence that at the same time as this resurgence, figures such as Sarah Silverman, Sacha Baron Cohen, and Larry David have displayed different aspects of antisemitism in their comedy. The question is: are these funny Jews making things better, or worse?

What Is Antisemitism?

“[The term] Antisemitism, especially in its hyphenated spelling, is inane nonsense, because there is no Semitism that you can be anti to.” –Yehuda Bauer, Professor of Holocaust Studies, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Antisemitism is a pervasive influence on Jewish culture. It drives Jewish philanthropic giving, inspires countless Jews to marry within the tribe, and, when push comes to shove, it connects with impressionable Jewish youth in a way no Friday night service can. Even in the first month of Zeek’s existence, and even in articles unrelated to the phenomenon (which we, unlike most Jewish media outlets, do not cover very frequently), it kept cropping up in the magazine. We even had to make an editorial decision about the spelling of the word, ultimately deciding that, unlike the OED, but like Emil Fackenheim and the Hebrew University “Center for the Study of Antisemitism,” we would spell it without a hyphen.

We did this because “antisemitism” is itself a contentious term. The word comes from the misconceived intersection of philology and racial studies, a moment when the study of racial characteristics seemed as worthy and objective a scientific project as the study of the history of languages (including the Semitic language group). Coined by the demonstrably racist Wilhelm Marr in 1879, the term was meant to make modern, race-based hatred of Jews seem different from, and more scientific than, the old religious hatred. Zeek decided on “antisemitism” as way to reflect the history and importance of the term over the past century, but hoped that the banishment of the hyphen would mark a break with Marr’s late nineteenth century German discourse, also avoiding the implication that being opposed to “semitism” is anything but a specific form of blind prejudice. (Getting rid of the hyphen also has the effect of disallowing the already disingenuous claim by Jews or Arabs that they can’t be antisemitic because they are “semitic.”)

Despite the usual rationalistic claims of the latest generation of antisemites, antisemitism is a generalized and irrational feeling of hatred towards Jews. In his seminal Réflexions sur la question juive (most recently translated as Anti-Semite and Jew: An Exploration of the Etiology of Hate), Jean-Paul Sartre called it a “passion” – a feeling of hatred that demanded a subject: “If the Jew did not exist, the antisemite would have to invent him.” Historically speaking, it is a set of Christian European prejudices about the Jews they ghettoized for more than a millennium that have spread wholesale to North America, Africa, Australia, and the Middle-East following the patterns of European colonialism. The general feeling has many specific examples which are outlined, surprisingly stridently, by David Mamet in his recently published screed The Wicked Son: Anti-semitism, Self-hatred, and the Jews. These spread either metaphorically (through things which are like the specific libel) or metonymically (through things which include or are included by the specific libel). These libels are based on a myriad of self-doubts, self-loathings, and insecurities experienced by mainstream European culture – especially in the face of an alternative – and turned on the Jews as the pre-eminent “other” in a continent with a negligible amount of other minority communities.

====

These libels have included specious interpretations of religious difference (e.g. that Jews use Christian blood to make matzah, a claim which scholar Gavin Langmuir notes is closely related, historically and philosophically, to the doctrine of transubstantiation), racial difference (Jews have big noses – a representation of the accuser’s sexual inadequacy, according to Sander Gilman), professional differences (Jews are financiers and financial cheapskates – because the Christian prohibition on usury and the Jewish continental network meant that they were needed and expert at transacting loans and payments at a continental level). Sometimes a piece of expert scapegoating just spreads. For example, water sources were so crucial and so precarious that, like thanking a Deity for a good spring, it made sense to blame the Jews for having a poisoned well.

In general, antisemitic Europeans blamed the Jews for anything they didn’t like. For religious antisemites the Jews were representatives of either Judas or Satan; for racial antisemites the Jews were ugly and in-bred; for cultural and paranoid antisemites the Jews were, in turn, the inventors and proponents of capitalism and Bolshevism. Even now, reactionaries parrot the tedious mid-twentieth century charge of Jewish moral relativism and yearn for a mythic time when Aryan mothers were sheltered by a blue sky and fed their babies on the milk of right and wrong.

The “New” Antisemitism

The “new” antisemitism, so much in vogue today, actually dates from the mid 1940s when the Shoah (a term against which Bauer also takes issue) and the establishment of the Jewish state in Israel gave the world two new Jewish-historical events to note. Really though, since Jewish victimhood was not essentially new (although the extent, the mechanization, and the national context were new and extreme) the change came from Israel showing it was a strong presence in the Middle-East – essentially since the end of the 1967 Six Day War. Once the Jewish state had showed it was secure on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, it provoked certain Muslims who believed that the land should belong to Islam (although they seemed to feel less resentment for Coptic Christians, for example). Also, in addition to this nascent Islamist antisemitism and the reliable bigotry of the far-right, the left-wing became a haven for a certain type of antisemitism that shelters below the wing of anti-Zionism.

This has led some commentators to label this a “new” antisemitism, but the newness is arguably nothing more than contemporary forms of the same old antisemitism blended in with some Quranic strains of prejudice that were formerly obscured by European predominance. Perhaps Islam has taken over the mantle of endemic antisemitism once the preserve of Christianity. Or perhaps the target of global political vilification is the small but surprisingly strong Jewish state rather than the target of national political vilification being a small but surprisingly strong Jewish community. Perhaps the Nazi’s state-based and groundbreaking propaganda gave new fuel and inspiration to age-old prejudices, but the reasons and the general form is still the same.

Zionism is the promotion of Jewish self-determination in the land of Israel – however that land is defined. This means that there are clear theoretical distinctions between being an anti-Zionist (arguing that the Jews do not have a right to self-determination), not being a Zionist (not promoting the right of the Jewish state to exist), and being opposed to the policies of the Israeli government (arguing against Ariel Sharon or Ehud Olmert in the same way one might argue against Bill Clinton, George Bush, or Tony Blair). There is likewise a clear theoretical distinction between legitimate anti-Zionism (a particular legal-historical perspective about collective rights) and antisemitism (prejudice against Jews). In theoretical and legal discussions, and by thoughtful people in the academy, these niceties are observed, likewise in the discussions of committed and engaged Jews for whom the distinction is personal and crucial (“I am a Jew, I am not a Zionist”). But the sad fact is that many (if not most) anti-Zionists are either unaware of the antisemitic cultural prejudices they are recycling, or are using anti-Zionism deliberately as a respectable cover for their antisemitism.

Comedy and Civil Society

The genius of the documentary The Aristocrats was that it succeeded in being both insightful and amusing. Usually there’s nothing as earnest as comedians talking about their comedy. Conversations about timing, sequence, and the exact length that will maximize laughs from a moulded plastic dildo are no funnier than similar conversations about investments in the futures markets. The product is different, but the deadly seriousness of the endeavour is not to be doubted. Yet however serious the work may be, like the futures market, comedy is deeply unpredictable and depends on social events, at the same time that antisemitism is an illogical and historically pervasive phenomenon. Comedy can never directly refute or destroy antisemitism. Instead, comedy can both ridicule it and educate about it in equal measures.  But this comedic aspect of Horace’s “delight and instruct” is part of a larger social picture. In a multi-cultural society the difficulty lies in mediating shared space so that different cultures can talk to each other about the things that matter to us all. Comedy takes our assumptions and sends them up, letting us have, if we want them, a place of tentative discussion with and about other groups. Since active antisemitism is an irrational “passion” and passive antisemitism comes from lack of knowledge of information, comedy is the ideal medium both to educate the accidental antisemite and viscerally (rather than logically) to undercut the deliberate one.

But this comedic aspect of Horace’s “delight and instruct” is part of a larger social picture. In a multi-cultural society the difficulty lies in mediating shared space so that different cultures can talk to each other about the things that matter to us all. Comedy takes our assumptions and sends them up, letting us have, if we want them, a place of tentative discussion with and about other groups. Since active antisemitism is an irrational “passion” and passive antisemitism comes from lack of knowledge of information, comedy is the ideal medium both to educate the accidental antisemite and viscerally (rather than logically) to undercut the deliberate one.

In following this line of thought, what is said in jest about antisemitism defines what is said in earnest. Although not a simple correspondence, the struggle to delineate the boundaries of acceptable speech is increasingly carried out in the arena of comedy. As Jews we laugh at ourselves and we laugh at the ridiculous prejudices that others have about us. However, without a degree of power over the arena, this comic performance comes across as a form of minstrelsy (making fun of one’s own oppressed group for the benefit of the oppressing group), or, if it is performed by another group, of downright prejudice. There is a similar debate going on about Dave Chappelle and his characters in the African American community: Is it acceptable to laugh at ourselves in front of others, possibly even exclusively for the benefit of those others? This was the professed claim in the case of the Danish cartoons – that a disrespectful comic performance by outsiders had taken place in a forum in which the Islamic world felt totally disempowered.

In discussing how comedy changes the way antisemitism is perceived, we are limited by the vocabulary available to us for talking about comedy. The laughter elicited for a joke about controlling Jewish mothers in The Hebrew Hammer is entirely different from the laugh inspired by Larry David eating the cookie of the baby Jesus. Different still is the laugh at Woody Allen thinking of himself perceived as a Hasidic Jew at the Hall’s dinner table. Different again is the Pamplona-esque “Running of the Jew” in Borat: Cultural Learnings… In our own self-observation we are obsessed with circumcision –from History of the World Part I to Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Shvitzin’” to the Late Night Players description of Matisyahu as “Hip-Hop from the Tip-Chopped.” It is hardly the worst stereotype to promulgate, but do we really want to reinforce the stereotypes of Jews as money-grubbing, mother-pecked, circumcised neurotics?

The danger of comedy is that it can reinforce stereotypes and trivialize hatred as well as belittling it, allowing the critique of the haters that “they are a joke,” but allowing them the excuse that “we were only joking.” The ease with which a group of people were encouraged to sing along with the abhorrently racist “Throw the Jew Down the Well” draws attention to antisemitism and its abhorrence, but it can also end up simply normalizing it. Clearly, the scapegoating of an almost invisible minority for the murder of the son of God is a pretty serious matter, and one which most churches have moved beyond. The parodying of the libel in Curb your Enthusiasm makes it difficult to take seriously at all.  Context is the Lens

Context is the Lens

Context is vital for understanding both antisemitism and the comedy that comes from it. Context provides the lens through which we see the performance – who makes it, to whom, and in what tone. The signs at airports mandating “no jokes beyond this point” are some of the latest reminders of how there is no longer any place for the slipperiness of humour when security is at stake. The context of antisemitism is likewise totally context-specific. For example, when the manager of an Italian restaurant in London seated us and went to fetch some sparkling water with the words “Ah yes, Jewish champagne,” it seemed like an antisemitic comment about being cheap. This was because he was not apparently Jewish and had no way of knowing whether we were Jewish or not. However, when a colleague – 8 years later, unprompted, and unaware of our previous experience – came out with exactly the same words upon being offered seltzer at our apartment in New York, that was, paradoxically, not antisemitism.

====

Similarly, when film star Arnold Schwarzenegger uses the term “girlie-man” in a political campaign he draws on a history of sexist and homophobic attitudes in a way that is barely acceptable, but which passes because his film persona is so unbearably macho that anyone, next to him at least, would appear lightweight. The slur was intended to mean that the subject of his comment was womanish (weak) and effeminate (hence, like a homosexual, weak, and perverse). To state this sentiment directly, however, with reference to the prejudices upon which he was drawing, would have alienated the very electorate who found the comment amusing. As a celebrity candidate, Schwarzenegger had access to forms of discourse no longer available to him as a governor. This is a classic use of humour, irony, and shifting contexts making it unacceptable to get away with an ad hominem attack.

With respect to their Jewish jokes at least, Silverman, Cohen, and David have the advantage of being openly Jewish comedians. It certainly does not fully excuse them from charges of antisemitism, since, as Mamet frequently avers, Jews can and do hate themselves. Even when Jews hate and critique the stereotypes that others have of us, we end up hating ourselves because we have internalized the stereotypes that others have of us. However, being Jewish does make a difference. As the letter the ADL sent Baron Cohen about his sketch including the song “Throw the Jew Down the Well” (which at points last year seemed to be the ring tone of every Jewish 15 year old). In that first letter they offered to help him work on the sensitivity needed to convey the subtlety of parodying antisemites to those people who might not “get it” – those very people for whom the context needs to be explained.

Of course, although Borat is offensive and ostensibly Kazakhi, Borat in America has nothing at all to do with Kazakhstan and everything to do with America. Baron Cohen’s prior incarnations of hapless outsiders were from Moldova and Albania, equally convenient East European screens upon which a gullible audience (in those cases British) could project their own prejudices. Borat’s crude and obnoxious antisemitism is excusable for its satirical intent, and not least because in his new film, his ostensibly Kazakhi dialogue is mostly Hebrew, continually allying the character linguistically and personally with those he professes to despise.

Context, however, works against others, especially if those individuals are entirely earnest and exist in a cultural milieu that carries extreme guilt about its treatment of the chosen subject of an attack. For example, for obvious reasons, contemporary Germany is extremely sensitive about comments made about Jews and the Jewish community. With its history of slavery and racial prejudice, the United States is sensitive to racial prejudice against African Americans. If Mel Gibson had said “All blacks are stupid” rather than his comments about Jews, he would be in far more serious trouble than the tiny media tempest aroused in the summer – especially if he had just made a historical film based on a long-discredited racial prejudice explaining how black men have a tendency to rape white women instead of how the Jews killed Christ. Imagine too if Gibson’s father (an avowedly strong influence on Gibson Jr.’s beliefs) instead of denying the Holocaust – or at least being intellectually close to those who deny it – was a white supremacist (or at least intellectually close with those who are). Given such a context Mel Gibson would have not been able simply to retreat to his ranch in “outpatient rehab” for his alcoholism.

So What Can Comedy Do?

So What Can Comedy Do?

So what can comedy do? Can it do anything, or is it, as Jay Leno said, just a different way of validating one’s own world view? Among the many things that Stephen Kercher traces in Revel with a Cause: Liberal Satire in Postwar America is the history of politicians co-opting comedians to either write speeches or merely directly champion them. From the beginnings of the televised world comedy has been co-opted, more or less successfully, by mainstream politics. The reason politics has gone to comedy is not because politicians want to subsidize performance art, but because comedy works.

Vitally, comedy as a genre can either ridicule or reinforce conventional behaviour. Those people who behave “absurdly” are ridiculed by comedians for standing out, either as representatives of anachronistic and unfair power or as exceptions to the accepted norms or stereotypes. From the court jester to Lenny Bruce this ambivalence has placed comics in an ideal position to articulate the usually unspeakable fears and discriminatory practices of racism in society. Because of its potential as a subversive genre comedy allows viewers to poke fun at themselves (and also at others) without heavy-handed self-righteousness or weighty melodrama, offering an invaluable vantage point from which to examine the emotionally fraught and politically sensitive issues of antisemitism.

There are four ways in which these jokes about antisemitism help the cause of fighting antisemitism insofar as the projection of an inchoate and irrational rage can be fought at all:

1. Mitigation: A Way To the Table

Because of the ambivalent status of comedy, what is said in jest can be intended or retracted. Paul Lewis discusses Rush Limbaugh’s virtuosic ability to both mean his accusations and also to label his victims as humourless if they complain. This can be a negative trait of ironic humour – to poke fun unaccountably – but by defusing a situation, by allowing a politician, performer, or public figure to take partial responsibility rather than insisting on unconditional blame, it can also allow them a way to the table. Insofar as antisemitism is the product of ignorance, comedy is one of the key tools to begin educating and informing. In education we speak of a “zone of productive discomfort” where students and teachers do new things with which they feel uneasy, but also learn from the experience. As I discussed above, comedy is a vital tool for tentatively trying ways of relating in public space between two nomoi (ethnic, cultural, religious, etc.) groups. Comedy can mitigate the discomfort we feel in relating to an unfamiliar group. For example, Ali G’s famous “Is it cos I is black?” comment to the police at a demonstration provided a comfortable starting point for a number of difficult and otherwise uncomfortable discussions about race in Britain.

2. Broad Discovery: Reveal and Influence the General Culture

In his rôle as a documentarian (and we might see Borat: Cultural Learnings… not in the Will Farrell but in the Errol Morris tradition), Borat elicits a multitude of responses. Yet these responses essentially fall into three camps: the excusably rude, the unbelievably tolerant, and the crassly bigoted. We feel sorry for those who are pushed beyond any semblance of normal provocation and end with rudeness (his dinner hosts, or the feminists for example); we feel affection for those who are pushed beyond any semblance of normal provocation and somehow maintain their courtesy and enthusiasm (the driving instructor most notably). What is frightening, though, is how many of the responses fall into the third category, from the gun-seller who doesn’t hesitate before recommending a good gun to defend against Jews to the utter homophobia at the rodeo and the extreme sexism of the frat boys (couched in the latest chat show psychobabble). Anyone who thinks that Borat “tricked” poor Americans into their homophobic, sexist, and racist comments in the film ought to check out the comments on any polemic internet article. Although nationally unacceptable, once stripped from public accountability and under cover of internet pseudonyms and in local branches, hate speech such as that shown by Borat: Cultural Learnings… is rife.

3. Decirculate: Make Words and Opinions Unacceptable

As many public figures have shown by surviving decades of public lampoon, comedy can only rarely bring down a politician. However, by making them objects of fun, comedy can take out of circulation specific words and habits of speech (for better and for worse). The media attention and ridicule vested upon George Allen’s use of the word “Macaca” is a way in which an offensive term has been taken out of circulation. From Stephen Colbert to John Podhoretz the ridicule heaped on this inappropriate term has brought it to brief attention, and, although it could suggest a new lease of life for a term of abuse, it has served as an educational point. Furthermore, comedy can defuse the hatred, or in Sartre’s terms the “passion,” of a particular libel. Standing up to denounce the belief that the “Jews killed Christ” requires bravery and will almost certainly not be effective. Enjoyment engendered by the farce of Larry David having eaten the cookie shaped like Christ – “You ate the baby Jesus…!” “The baby Jesus? I thought it was a monkey.” – makes it a difficult slander for racists to use.

4. Destabilize Power: Bring the Incumbent to Level Ground

Whether the powerful entities in question are words or officials, good satire is always at the expense of the powerful. Kercher starts with a quotation from Orwell: “The truth is that you cannot be memorably funny without at some point raising topics which the rich, the powerful, and the complacent would prefer to see left alone.” Borat replied to the Kazakh government banning his website with this mini video file. The more that he is picked on, the more his outsider status grows and the more the character looks down the ladder to pick on those below him – satirizing, as he does so, the people above him who are looking down the very same ladder with the very same prejudice. This is not always a positive strategy. As politically correct terms were established to replace formerly offensive terms, PC became the new authority to be shocked. Borat’s use of the terms “Vanilla Face” and “Chocolate Face” are offensive, but along with reactionary homophobic comments and the objectification of women are – despite their appearance but made obvious by their context – nevertheless part of a vaguely leftist reaction against political correctness. By destabilizing received power, each cycle (whether the TV sweeps cycle, the four year electoral cycle, or the thirty year generational cycle) gets a better chance to be heard.

History repeats itself, first time as tragedy and second time, we hope, as farce. Making extremely serious subjects farcical is bound to upset some people, but this is the rôle of socially responsible comedians. In a world where many journalists eschew serious balanced or investigative reporting as too demanding or professionally inopportune or, alternatively, work hard in the face of extreme adversity and are killed for it (like Anna Politskaya), there is a clear need for comedians to point out the elephants of bigotry, nepotism, and deceit in the room. Stephen Colbert did this hilariously to the reporters themselves by at the White House Correspondents dinner earlier this year. The new sub-genre of Cringe Comedy carries the transgressively awkward yet self-righteous social correctness of its herald George Costanza (from Seinfeld) into the realms of political and cultural correctness. Again and again cringeworthy moments the likes of The Office, Napoleon Dynamite, The Colbert Report, Sarah Silverman, Larry David, and Borat bring us face-to-face with the disjunctions of expectation and action.

History repeats itself, first time as tragedy and second time, we hope, as farce. Making extremely serious subjects farcical is bound to upset some people, but this is the rôle of socially responsible comedians. In a world where many journalists eschew serious balanced or investigative reporting as too demanding or professionally inopportune or, alternatively, work hard in the face of extreme adversity and are killed for it (like Anna Politskaya), there is a clear need for comedians to point out the elephants of bigotry, nepotism, and deceit in the room. Stephen Colbert did this hilariously to the reporters themselves by at the White House Correspondents dinner earlier this year. The new sub-genre of Cringe Comedy carries the transgressively awkward yet self-righteous social correctness of its herald George Costanza (from Seinfeld) into the realms of political and cultural correctness. Again and again cringeworthy moments the likes of The Office, Napoleon Dynamite, The Colbert Report, Sarah Silverman, Larry David, and Borat bring us face-to-face with the disjunctions of expectation and action.

It is notable that all of the abovementioned comedians are dealing with old manifestations of antisemitism – things that our grandparents would have recognized. Larry David does brilliantly satirize the superficiality of the Survivor-generation by juxtaposing a “Survivor” with a survivor of the Shoah. Still, with that exception there is almost no engagement with the Nazi-libel (Europe could never forgive the Jews for Auschwitz), anti-Zionism as antisemitism, or – with the oblique exception of Borat’s “9-11” comments – Islamism as a medium for virulent antisemitism. Also, comedians do not work in a vacuum. Rather, they work in a world where their words circulate, are commented upon, and are changed. Comedy should not be banned, it should be encouraged. But just as one lens cannot make a telescope, a pair of glasses, or even a microscope, a single perspective will not help one see the world let alone help one change it. Such change is something that comedy cannot not achieve because it is not trying to. That is our job in the audience – changing society.

Generally I don’t read article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very compelled me to try and do so! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thanks, very great post.

I do not even know the way I stopped up here, however I assumed this post used to be great. I do not know who you are however certainly you are going to a well-known blogger when you aren’t already Cheers!

Simply killing some in between class time on Digg and I found your article . Not usually what I choose to read about, but it was completely price my time. Thanks.

And, clubbed with the superior precision technology that is so characteristics of Tag Heuer watches these timepieces are a coveted possession for all women who appreciate quality.

Wow!, this was a top quality post. In theory I’d like to write like this too – taking time and real effort to make a good article… but what can I say… I procrastinate a lot and never seem to achieve anything