I lived in a neighborhood renowned for its ugliness and unlivability and worked with its children. It overpowered me sometimes though, how much I loved my group of six-year olds who couldn’t sit still and couldn’t understand my Hebrew half the time and how when I walked through the cats, litter, Russian grandparents and raggedy kids of the neighborhood, I felt at home. I also began to discover a love for Israel and its people… I realized that I couldn’t imagine living outside of Israel, that I belonged to the country and everyone in it.

So begins the first issue of Jobnik! , an extraordinary independent comic series by Miriam Libicki, relaying her experience as a Jewish-American girl from a devout Orthodox family who makes aliyah at the age of 17. Like most able-bodied Israeli citizens, she serves in the Israeli army. Diagnosed as “introverted and excessively emotional, as well as possessing poor Hebrew skills” by military psychologists, it is clear to everyone around her that she is not fit to be in the army. Still, she obtains a desk position as a secretary and file clerk for an infirmary at an Armored Corps training base in the Negev. Such positions are labeled derogatorily as the destiny of “Jobnikim” –pencil-pushing soldiers with desk jobs and other  non-essential positions. But rather than staying behind a desk, Miriam floats to a variety of departments, including the kitchen where some of her more disgusting tasks include scrubbing out a cauldron bigger than her and peeling mounds of vegetables outside of a garbage dumpster. In the process, readers learn very quickly what happens to a Diaspora Jew internally when Israel is no longer a vacation spot, but a home – a distant and beloved fantasy emerging as a complex, mundane, and at times violent reality.

non-essential positions. But rather than staying behind a desk, Miriam floats to a variety of departments, including the kitchen where some of her more disgusting tasks include scrubbing out a cauldron bigger than her and peeling mounds of vegetables outside of a garbage dumpster. In the process, readers learn very quickly what happens to a Diaspora Jew internally when Israel is no longer a vacation spot, but a home – a distant and beloved fantasy emerging as a complex, mundane, and at times violent reality.

Rather than focusing on grand political narratives such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, most of Miriam’s story centers upon failed love affairs with men who seduce her into sex and dump her – Shahar, Asher, and Roi in rapid succession. The first two are soldiers on her base, the last a night watchman at a building near her sister’s apartment. Inevitably, she falls for each man quickly, fools around with him, and then cries with regret and shame when he tires of her soon after. While such an introduction might suggest that the cartoonist writing from an autobiographical perspective has produced self-absorbed fluff, rest assured that she has not. The complexities and challenges of Israeli life come out naturally with deep nuance in each of these interpersonal conflicts.

What makes Miriam such a likeable (though at times irritating) character – in a Bridget Jones sort of way – is her “flaw” of wearing her heart on her sleeve. She is extremely naïve; yet this is a naïveté borne out of a belief in the inherent good of people that maintains itself no matter how often she gets burned. This is an admirable quality, even if the reader occasionally shakes his or her head wondering how Miriam could let herself be fooled so easily. This perception is balanced by the knowledge that at her core there is nothing wrong with Miriam as a person. She is merely a gentle sort who has stumbled into a place where gentleness is not a practical quality.

From an Israeli perspective, however, Miriam’s naïveté is the result of being raised in a different culture, one that hasn’t experienced war at its doorstep so often. For example, she begins dating Shahar during the period just prior the start of the Al-Aqsa Intifada in 2000. At the same time, Shahar takes a week off from Miriam in order to sleep with another woman whom he calls “a friend.” When battles begin erupting across the occupied territories, he is sent to the front. She tries to call him but he refuses to answer his cell phone. Later, when Shahar more or less dumps Miriam, he uses the schism between native born-Israelis and new immigrants to belittle her. His rationalizations, though undoubtedly cruel, bespeak the differences in their cultural upbringings.

Miriam: I can’t deal with what’s happening. I’m freaking out. Shahar: Oh, this? You wouldn’t be freaking out if you were Israeli. Miriam: I kept calling you ‘cause you said you were going to to the territories! All I wanted to know is if you were alive! Shahar: Somebody worrying me is exactly what I don’t need right now. I do like you but I can’t be here for you. Miriam: You can’t answer a pelephone. [Israeli slang for cell-phone -Ed.] Shahar: Miriam, I can’t. Do you understand? Miriam: No.

Throughout the comic, more recent developments in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict offer an ever-present backdrop, making clear the very real brutalities that both sides commit. These range from the lynching of two Israeli reservists in Ramallah and the near murder of a British photographer who tried to capture it on film to the killing of 12-year-old Mohammed Aldura during crossfire between Israeli soldiers and Palestinians. What’s nice is that Libicki avoids avoid soap-box discussion, effectively keeping the comic from getting didactic or preachy, giving readers the message that she respects and trusts them to form their own opinions about the conflict.

“The Biggest Mofo of a Cookpot You Ever Seen” In her narrative, art and composition play an important role. In issue three, for example, when Miriam and Asher are watching television and see the mangled corpse of the reservist being thrown outside a window in Ramallah, the words of the British photographer who witnesses the event and is nearly killed as well appear in white jagged squares – indicating in typical comic-book format that these words are being transmitted electronically:

Look how many years they’ve been talking peace – since 1993. Then within just a couple of weeks, they are at each other’s throats. It seems that it’s easier to hate than forgive.

In the same issue, the reader finds Miriam sitting in the midst of 16 separate squares in which the news is presented from a newspaper article. Split into fours, Miriam is placed squarely in the middle of each set, looking more and more dejected as the words continue; still, there is no clear connection following one column to the next. This communicates what many people might experience when trying to track the peace process and its many failures. There comes a point in which the words of reportage and explanation blur and become incomprehensible. There are so many political twists and turns on both sides, it is impossible to keep up or understand the story.

As for the quality of the art as a whole, the first issue is not very strong. The pictures are flat and two-dimensional, a jagged zigzagged roughness running through Libicki’s pen strokes and lack of texture that makes the comic unpleasing aesthetically. By the fifth issue there are radical improvements. Apparently trading her pen for a pencil and kneaded eraser, her later method allows for far smoother transitions from white to light grays to dark grays to black, making the overall effect smoother, more fluid, more subtle, and more three-dimensional. Backgrounds, as well, become more detailed.

The most interesting example of the artist’s composition appears with a scene of Miriam cleaning “the biggest mofo of a cookpot you ever seen.” Crouching inside the pot in three different pictures bunched on top of one another with pipes as backdrop, the reader cannot help but empathize with Miriam’s sense of entrapment, compellingly communicated by the round metal cauldron walls surrounding her. As she scours the pot, she obsesses about Asher who has recently dumped her. The cauldron moves towards symbolizing her tendency to go in circles, repeating unhealthy actions again and again.

Arsim, Dosim, and Frechot In the midst of all of this, gender issues play a very strong role. One can’t help but sense that the Israeli men who bed her have completely closed themselves emotionally. As a sheltered young woman raised in an American suburb, she does not have the skills to deal with Israeli men the way her female sabra counterparts might. This becomes especially clear when Miriam begins talking to Hila, who Asher has been trying to date while fooling around with her. Hila instigates a meeting between the three of them and digs right into Asher, saying bluntly, “You treated me and her exactly the same way!” After their meeting, while Miriam wallows in self pity, Hila, in direct no-nonsense Israeli fashion, sets her straight.

Arsim, Dosim, and Frechot In the midst of all of this, gender issues play a very strong role. One can’t help but sense that the Israeli men who bed her have completely closed themselves emotionally. As a sheltered young woman raised in an American suburb, she does not have the skills to deal with Israeli men the way her female sabra counterparts might. This becomes especially clear when Miriam begins talking to Hila, who Asher has been trying to date while fooling around with her. Hila instigates a meeting between the three of them and digs right into Asher, saying bluntly, “You treated me and her exactly the same way!” After their meeting, while Miriam wallows in self pity, Hila, in direct no-nonsense Israeli fashion, sets her straight.

====

Hila: He’s a son of a bitch, that’s what he is. He uses girls. Miriam: He just never liked me. He liked you. Hila: He lied to both of us. I never fell for it. Miriam: But I did and now he says he’ll never talk to me again. Hila: Don’t talk like that. It’s better he’s not talking to us. You’ll see.

Meanwhile, the complex schisms of Israeli society – be they new immigrants vs. sabras, secular vs. religious, Jew vs. Palestinian, Sephardi vs. Ashkenazi – unfold as an everyday part of the setting and environment in which Miriam lives. Libicki often uses flare-ups of temper to communicate these conflicts, such as when Yossi, an openly gay character and a fellow soldier (who loves the 1998 Eurovision winner, transsexual singer Dana International), criticizes his father’s support for the right-wing National Religious Party. After his father claims yet again that the NRP should be “running this country,” Yossi strikes back:

You are running this country. Fucking primitives! That’s why this country is such a third world backwater. This whole country makes me sick. Tel Aviv is the only place where you dosim don’t…

Dosim, Libicki explains in a footnote, is often used as a derogatory term for religious Jews. This footnote, rather than a long speech, communicates the religious-secular schism in clear terms for the reader. It is also but one example of Libicki’s effective and sparse use of Hebrew slang, providing the reader with intimate sounds of Israeli culture and the conflicts expressed through language. Dosim, it should be noted, can be used as a “cutism,” the kind of insulting label reclaimed by insiders of a hated group – like “Yid” and “Heeb” of late – as a way of taking away the words’ power to hurt and proudly identifying with whatever the opposing group finds offensive or threatening.

Yossi uses two other words that in various contexts can be used as insults or cutisms. One of them is freha, meaning bimbo, which is often a derogatory terms for Sephardi women. During a party to celebrate the discharge of an Israeli soldier named Shlomit, he throws on and begins dancing to the Ofra Haza classic “Shira Hafreha” – “The Bimbo Song” – singing right along:

I’ve got no head for long words and you’re kind of a long word yourself. I feel like dancing, I feel like laughing, I wannit all day, I wannit all night, I wanna shout, ‘I’m a freha.’

Yossi is the most interesting of all of the characters becuase of the ways in which he encapsulates the contradictions of Israeli society. As a Sephardi Jew whose cultural background is Arabic and as a gay man from a religious family serving in the Israeli army – all without experiencing discrimination – he defies easy categorization. As such, freha becomes the perfect category in which to proudly proclaim himself as a Sephardi gay man.

The other insult/cutism Yossi uses is arsim – an expression linked tp working-class Sephardi men in a tone similar to the American term “Gino” – to describe Asher and his roommate to Miriam. Arsim, derived from the Arabic word for pimp, is used by Yossi not as a cutism but as a definite insult: “Pair of Arsim from Dimona!” he spits, illustrating the sort of hyper-masculine gender roles against which he rebels, even while he serves as a medic in the army. He also calls Miriam “bruiser” and “girl thug” both charmingly ironic and ridiculous. And when Yossi introduces Miriam to his grandmother, these layers of gender, ethnic, and political schisms combine with dark humor:

Yossi: Savta, this is Maryam. She’s Palestinian. Savta: No, she’s not. She’s Jewish. I can see she’s a Jewish girl. Yossi: No, she’s Palestinian, Savta. She’s Arafat’s daughter. We’re getting married. Savta: Jew! Not Arab!

The machismo Miriam experiences from Israeli men – against which both Hila and Yossi hold their own very well – runs counter to the experience she has had with the one previous American boyfriend she mentions in her comic, a very sweet fellow from her drawing-class named Stew. He even tells her he’s in love with shortly before she makes aliyah. Gentle, creative, kind, sensitive, Stew is the polar opposite of the men she meets in Israel. As a result, there is a sense of allegory in Libicki’s work. Having moved out of Israel herself, the men who seduce her parallel Israel as a traitorous beloved who fails to live up to her expectations – such as when Asher tries to have anal sex with her without any kind of gentleness or foreplay.

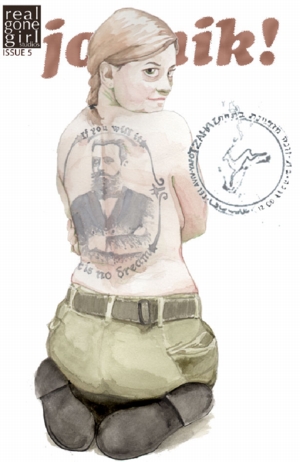

The interweaving of Zionism with sexuality becomes especially clear on the cover of Jobnik!’s fifth issue where a topless Miriam provocatively displays a tattoo of Theodore Herzl on her back, his classically austere pose with arms folded circled by calligraphy of his most famous maxim: “If you will it, it is no dream.” Looking over her shoulder with doe-like eyes and a coy grin, the reader finds Miriam’s arms folded across her breasts in a show of playful pseudo-modesty. Meanwhile, she dons combat boots and khaki pants.

Though Jewish-themed tattooing is already starting to become a cliché in contemporary urban bad-boy/bad-girl Jewish art, in this context real meaning lurks behind the shock value of the picture, as the author’s attachment to Israel is sensually marked on her skin. This is made even more complex by Miriam’s masochistic sexual ties with Israeli men who treat her badly.

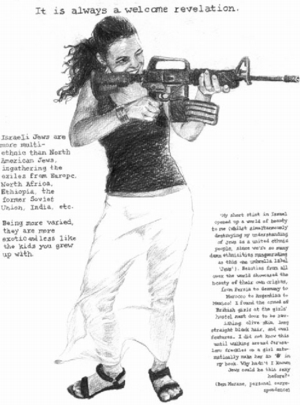

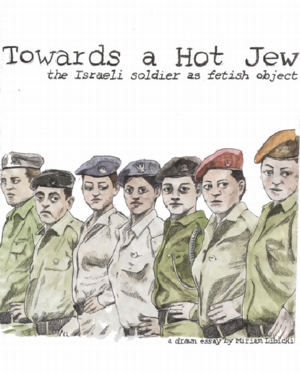

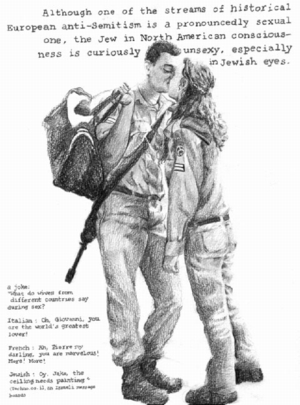

Towards A Hot Jew Having moved away from Jobnik! temporarily, Libicki has also produced a very interesting single-issue “comic” (for lack of a better word) called Towards a Hot Jew: The Israeli Soldier as a Fetish Object. Labeling it a pictorial essay, Libicki has produced a very nice complementary work to Jobnik! which explores pop culture body image of Jews in the Diaspora versus those in Zionist literature. Zionist publications often feature virile, tough male and female soldiers. Quoting Jewish feminist Riv-Ellen Prell and cultural theorist Maurice Berger, Libicki explores the “New Jew” or “muscular Jew” of Zionist literature as a reaction to the image of the weak, ghetto-dwelling, bookish, and mercantile Jews of the Diaspora, particularly in Europe. This a powerful draw for non-Israeli Jews, including Libicki, whose self-portrayal in Jobnik! as a soft, suburban American girl amidst the hardened sabras for whom she both pines and lusts play off of these very stereotypes.  Towards a Hot Jew uses real photographs of Israeli soldiers – beautifully, precisely, and skillfully recreated through pencil-drawings – to illustrate a mini-thesis about how anti-Semitism has affected Jews through body-image, making them feel sexually inadequate and unattractive. This is particularly true, she points out, in North America, where stock characters in popular culture – often created by Jewish writers, directors, and producers – are all too common. These include hen-pecked, nerdy, neurotic, hyper-intellectual Jewish men and loud, vulgar, overly adorned, overly bedecked, bejeweled, emasculating Jewish women. Using a picture of two strong young attractive male and female soldiers kissing to represent the polar opposite of such images, Libicki quotes a joke from an Israeli message board.

Towards a Hot Jew uses real photographs of Israeli soldiers – beautifully, precisely, and skillfully recreated through pencil-drawings – to illustrate a mini-thesis about how anti-Semitism has affected Jews through body-image, making them feel sexually inadequate and unattractive. This is particularly true, she points out, in North America, where stock characters in popular culture – often created by Jewish writers, directors, and producers – are all too common. These include hen-pecked, nerdy, neurotic, hyper-intellectual Jewish men and loud, vulgar, overly adorned, overly bedecked, bejeweled, emasculating Jewish women. Using a picture of two strong young attractive male and female soldiers kissing to represent the polar opposite of such images, Libicki quotes a joke from an Israeli message board.

‘What do wives from different countries say during sex?’ Italian: Oh, Giovanni, you are the world’s greatest lover! French: Ah, Pierre, my darling, you are marvelous! More! More! Jewish: Oy, Jake, the ceiling needs painting.

The results of this kind of marketing become quite obvious, as revealed by Libicki’s use of some very telling excerpts.

‘I think Israel would be a great place for me to live and find a partner. There’s nowhere else I feel so comfortable as a gay man and a Jew. I tried to buy an Israeli rainbow flag to hang out my window, but I kept getting distracted by the cute soldiers.’ (Jonathan Goler. Israeli trip participant)

‘My short stint in Israel up a world of beauty to me (whilst simultaneously destroying my understanding of Jews as a united ethnic people…)…Beauties from all over the world showcased the beauty of their origins, from Persia to Germany to Morocco to Argentina to Mexico… Why hadn’t I known Jews could be sexy before?” (Ben Murane, personal correspondence)

Accompanying another photo-based pencil drawing of a soldier suggestively holding his belt buckle, leading a Palestinian with hands bound, is a quote by none other than the infamous Joe Sacco, an anti-Zionist graphic novelist:

‘And what about the boys? Ooo la la!! I mean, look at this Dude! He’s taking five on the Old City ramparts… gazing over annexed Arab land… doing a welcome-to Marlboro Country. Even I’m pressing my legs together.’

Libicki then writes:

In the West, where sexuality and sexual attraction are tied up with sin, shame and furtiveness, the person you are told to disapprove of is almost sexy by default. Here I think of such artists as Tom of Finland and Attila Richard Lukacs. [Emphasis added]

Tom of Finland and Attila Richard Lukacs are gay artists who have produced eroticized images of Nazis, the former from Germany back in the 1940s, the latter in contemporary times focusing on gigantic murals of skinheads. For Tom of Finland, who has somewhat simplistically been criticized for depictions of stereotypically hypersexual images of black men (his white men look quite similar), Nazi images make up a very small portion of his overall work. Lukacs, however, has showcased Nazi-themed murals in prominent galleries across the world. Libicki ends the pictorial essay by writing:

By the quirks of history, propaganda and the voyeuristic urge, we have arrived at the New Jew: an adorable oppressor for every persuasion.

And here the reader finds a tension in Libicki’s work. On her website, she has an illustrated manifesto in which she states that she wants to challenge generalizations about Israelis as “killing machines, or innocent victims, or older brothers of Christ or the puppets of American Policy.” Calling herself “Zionist and Left-wing,” she is honest about the emotionally and tricky terrain in which she treads:

My politics are not simple right now… as I’ve gone from being a suburban Jewish-American girl to an Israeli, later a soldier (but always seen as an American) to an Israeli- American living in Canada without many Jewish friends. I wish I could say I have no politics but I do. They’re in everything I write.

Critical of left-leaning anti-Israel zealots, some of whom harassed her through placing anti-Israel messages on her dorm room door at the University of Seattle – as well as Evangelical Christians whose support of Israel is based on the ideology that Israel needs to exist so that when Jesus returns, Jews will repent and become Christian or burn in hell – Libicki has set out a tall order for herself: trying to find a politics in-between or maybe even an ideology that transcends the politics. The inconsistencies between her pictorial essay in which she calls Israeli soldiers (or the depictions thereof) “adorable oppressors for every persuasion” and her desire to get away from such extreme labels in her manifesto highlight the difficulties and contradictions experienced by many Jews who believe in the existence of a Jewish state for the purpose Jewish survival, while hating so many of its policies and practices.  Still Carrying Herzl on Her Back To return to Jobnik!, issue five, in which her desire for Israel becomes both sexualized and satirized through the Theodore Herzl tattoo on her back, Libicki offers a beautiful and brilliantly creative juxtaposition. Miriam gets approval for an extended leave to travel overseas through the “Association of the Wellbeing of Israeli Soldiers.” During a security debriefing in which she is instructed to never identify herself as an Israeli soldier, she makes a flippant joke about the nonexistent Theodore Herzl tattoo, earning her a dour expression from the security agent. Then she goes to Toronto for a Moxy Fruvous convention (Canadian folk-pop band) and has reoccurring flings with a man named Bill, whose back is covered in large blotchy birth marks. Post-coitally one night, Miriam – artist the she is – cannot help but run her fingers along their edges.

Still Carrying Herzl on Her Back To return to Jobnik!, issue five, in which her desire for Israel becomes both sexualized and satirized through the Theodore Herzl tattoo on her back, Libicki offers a beautiful and brilliantly creative juxtaposition. Miriam gets approval for an extended leave to travel overseas through the “Association of the Wellbeing of Israeli Soldiers.” During a security debriefing in which she is instructed to never identify herself as an Israeli soldier, she makes a flippant joke about the nonexistent Theodore Herzl tattoo, earning her a dour expression from the security agent. Then she goes to Toronto for a Moxy Fruvous convention (Canadian folk-pop band) and has reoccurring flings with a man named Bill, whose back is covered in large blotchy birth marks. Post-coitally one night, Miriam – artist the she is – cannot help but run her fingers along their edges.

Bill: Tracing the continents? Miriam: I like them.

In opposition to the symbolic Theodore Herzl tattoo on her back, representing Israel, Bill’s back illustrates a larger world, the Diaspora. His skin becomes an oracle, predicting her future: galut – namely, exile. At that point Libicki transcends concepts of Zion and galut, homeland and Diaspora. There is a growing sense as Jobnik! progresses that Miriam’s home is in her own skin, the place where her sexuality and sensuality are kept as well. This is the reason why the Herzl tattoo on her back and the continents on Bill’s back work so well in juxaposition.

Today, Libicki lives in Vancouver. In August 2006, she produced Ceasefire based on her experience in Vancouver watching the recent war in Lebanon from abroad, then visiting her family. Drawn in beautiful water colors, Libicki reveals a great deal of artistic versatility. One of her concluding comments is especially powerful.

I’m so glad it’s over. I’m glad for everyone’s brother and boyfriends. I’m glad I’ll be coming back home as the girl who saw her family, not as a girl who’s been visiting a war. I’d like to move in polite circles without being the Israeli monster who laughs and bombs children… Or at least I’m bombing fewer children than before. [Emphasis added.]

Since Sept 11, 2001, the political wings of left and right have become frighteningly extreme. In the far left, often it seems any support for Israel’s existence is equated with supporting American right-wing domination in the Middle East, while on the right, criticism towards Israeli policies, as well as the US’s military backing, is labeled as traitorous and anti-Semitic. Jews like Libicki who retain emotional, spiritual, and familial connections with Israel while criticizing its policies are treading in territory that has always been difficult, but today is even more so due to the twin but oppositional forces of Islamophobia and anti-Americanism. What is precisely so appealing about Jobnik! and Libicki’s work as a whole is that she is not scared to portray her contradictions and divided loyalties. She suggests no political posturing or wanting to please one polarized political group over another – though certain sections could certainly be isolated and misquoted to seem that way. As her comic progresses, Libicki’s art reveals additional layers of texture and depth. And as Miriam’s story continues to unfold, Libicki, her creator/human counterpart, is definitely one graphic artist to watch.

I needed to post you the little observation to be able to give many thanks as before for those breathtaking suggestions you have documented at this time. It has been quite shockingly generous with you to convey without restraint exactly what a lot of people could have sold as an ebook to get some dough for their own end, specifically considering the fact that you could possibly have tried it in case you desired. The concepts also served to become fantastic way to be certain that many people have similar passion just like my own to figure out good deal more on the subject of this condition. I believe there are millions of more pleasurable moments ahead for folks who examine your blog post.

Thanks lots because of this hassle-free internet site. i like actively playing transformice display game.