I am back in the place that I wanted to get away from, with its self-styled citizenry; its self-proclaimed superiority; its forest of buildings that make you feel small. New York City: the place of superlatives, where anyone who’s made it here wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. I am back, even if I’m not exactly sure why.

I am back in the place that I wanted to get away from, with its self-styled citizenry; its self-proclaimed superiority; its forest of buildings that make you feel small. New York City: the place of superlatives, where anyone who’s made it here wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. I am back, even if I’m not exactly sure why.

Raised in America, I have spent the past seven years ¬- just about my entire adult life – living in Israel. Now I have decided to move back, and to make a new life here. Walking down Broadway, riding the subway, shopping at Fairway, I could be mistaken for a lifetime New Yorker, but I feel like a foreigner. This isn’t really home. But then, Israel wasn’t entirely home, either.

I never planned to move to Israel; it just happened. I was living in Boston and working at a school, so I had the summer off. My sister, who was studying at Hebrew University for the year, called me and said, why don’t you come for the summer? I sublet my place, left some stuff with some friends, and went with a duffle bag. I told myself, maybe you’ll just go for the summer. I told myself, maybe if you’re really happy, you’ll stay.

I didn’t come with a specific ideology, or thinking that this is the land God gave us. I came because my sister had an apartment on a little street in Jerusalem, and because it turned out the apartment had a little yard in the back with a little grass and some big overhanging trees that brushed against the open windows at night (there were no screens and the mosquitoes came in), and the upstairs neighbor was a crazy old man who yelled at us every time we opened the back door (he said it blocked his view), and we complained to our landlords, an elderly couple, who said, mamales, don’t let him upset you; you’re young, go out! And what I found in Jerusalem was a sun so hot that almost every time I went out I had to come right back home and take a shower. And I discovered a little café in a back alley near the center of town that served almond tea steeped in milk and served with honey and I bought tomatoes and cucumbers at the shuk that were so good that I ate them just with olive oil and salt and that was a whole meal, and I found a cabdriver who didn’t charge me when he got lost, and the beach was only a bus ride away. And when I went to synagogue on Friday nights, for the first time in years, I heard new tunes to the familiar prayers, and strangers smiled at me, and nobody cared what I was wearing.

So I decided to stay – not forever, just for the next foreseeable piece of it. My sister went back to the States, and I moved into another apartment. I enrolled in Ulpan and began looking for a job. I was amazed by so many things, especially by how easy it was to meet people, how quickly strangers or friends of friends became friends. I did things I had never done before: I took a meditation class, I volunteered at a religious-secular dialogue group, I went  to a three-day music festival at the Dead Sea during Passover and slept under the salty stars, I danced at weddings of people I had just met. I felt more at home than I had ever felt before: in America I had felt Jewish; in Israel, I felt like myself. I suppose it’s a cliché, but it never felt like one.

to a three-day music festival at the Dead Sea during Passover and slept under the salty stars, I danced at weddings of people I had just met. I felt more at home than I had ever felt before: in America I had felt Jewish; in Israel, I felt like myself. I suppose it’s a cliché, but it never felt like one.

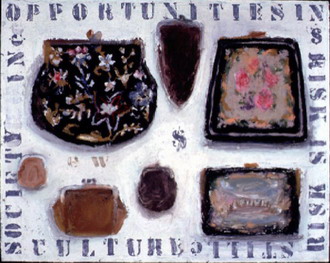

It was all very different than the life I had lived. Raised in a traditional Jewish household in Chicago, I went to Jewish day school through 12th grade, did a year of requisite study at a women’s seminary in Jerusalem, and went to college in New York, where, true to my upbringing, I was active in Jewish life on campus and never dated a non-Jew nor went to loud parties. I was doing my best, but it just didn’t feel right. I went to Shabbat services, but increasingly felt it was nothing more than a spectacle: hundreds of young people dressed in designer suits looking to see and be seen. The local synagogues offered more of the same: high-end social clubs, high-heels required. I saw this most acutely in my experience with the so-called “modern Orthodox” world, but it was a theme that ran across the spectrum of New York Jewish life – religious, secular, or somewhere in between. Where I was looking for spiritual liveliness and meaning, I found an empty void or worse, a self-satisfied materialism.

By the time I was in my senior year of college, I was pretty certain that the Jewish scene in New York was not for me. There was something about the fast-paced, get-ahead, make-money ethos of the surrounding culture that seemed to get mixed in with Judaism, making it feel like a competitive sport. I thought I would feel more at home in a smaller, more low-key Jewish community, and that was one of the reasons I moved to Boston. But there wasn’t very much I was connected to there. Living there felt random, as if I’d picked a place on a map with my eyes closed and put a thumbtack there.

While the actual packing-a-bag-and-getting-on-a-plane felt spontaneous, moving to Israel was probably a long time coming. My parents met as hippie volunteers on a kibbutz in the seventies, and I was born in Jerusalem a few years later. Although we moved back to the States when I was nine months old, before I could learn a word of Hebrew, and although I never visited until I was a teenager, Israel was part of my growing up. In school and summer camp, my teachers and counselors told stories of the Jewish people returning to their ancient homeland after two thousand years, irrigating the desert to make it bloom. But I also learned the stories my parents told – meeting in the grapefruit orchards, my mom falling in love with my dad when he offered her almonds and looked at her with his blue eyes, eating Shabbat meals at their friends’ homes in the Old City, bathing me in a sink in the bathroom of the King David Hotel when the hot water in their apartment ran out. It was a fabled, fantastic reality that existed just beyond the looking glass, and was part of the story I told myself about myself.

It’s not easy being a Jewish woman in America. The pilloried, parodied Jewish woman has been a fact of American popular culture since at least the end of World War II. Woody Allen, Phillip Roth and their progeny have made careers lampooning the Jewish American woman, portraying her as either a stuck-up “JAP” beholden to her parents or as a smothering, guilt-inducing “Jewish mother,” all the while holding up the effortlessly graceful non-Jewish woman as the feminine ideal. More often than not, female Jewish characters in television, movies, and novels are portrayed as loud, demanding, and altogether shallow. Yet one rarely hears much real concern about this situation. Is there some tacit agreement among viewers that these characters are dead-on? Have we all grown so accustomed to seeing this stereotype that we don’t expect anything more nuanced or complex?

As part of my “re-acculturation” program to New York, I have allowed myself the luxury of catching up on some TV shows I have missed, and I admit a certain fondness for Larry David’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” I also admit to being somewhat horrified by it. David’s eponymous character is explicitly Jewish while his TV wife, Cheryl, is explicitly Not. Where Cheryl is sweet, attractive and even-tempered, the Jewish wives of Larry’s (Jewish) friends are so obnoxious as to be almost unwatchable. Where Cheryl is a balancing force for Larry’s antics, the Jewish wives do nothing but harangue.

====

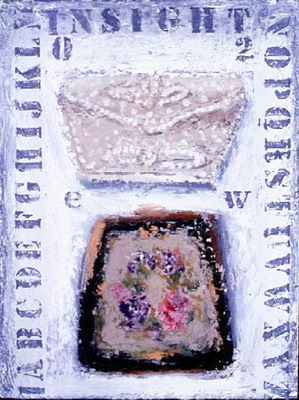

Whether I was conscious of it or not, I now see that I was looking for another model of what it meant to be a Jewish woman when I moved to Israel. I don’t know if I found it in Jerusalem, but I did find a lot of lost pieces of myself. I was inspired by the Israeli women I knew and saw around me. They had a certain confidence not necessarily because of looks, wealth or achievement, but simply – it seemed to me – from the very fact of being. Israel has a myriad of fractured and often warring subcultures, but I saw this trend across the board: in the well-to-do young women from Tel Aviv in their hyper-hip clothes, in the modestly dressed ultra-Orthodox women from Meah She’arim,  in the faithful earthiness of “settler” women in their flowing, colorful scarves and wrap-around skirts. The women I met, or saw walking down the street, seemed to have something their American counterparts do not. A sense of self rooted in a sense of place – and a knowledge of themselves borne of faith, in God or in themselves. They seemed to trust themselves in a way that I was only just learning to. Seeing them made me feel I was in the right place – that the lessons I needed to learn were the lessons being taught, and that I could learn them just by looking, by watching, by sitting by the Western Wall and daydreaming. From the women of the land of Israel I learned something about how to be alive, even amidst death.

in the faithful earthiness of “settler” women in their flowing, colorful scarves and wrap-around skirts. The women I met, or saw walking down the street, seemed to have something their American counterparts do not. A sense of self rooted in a sense of place – and a knowledge of themselves borne of faith, in God or in themselves. They seemed to trust themselves in a way that I was only just learning to. Seeing them made me feel I was in the right place – that the lessons I needed to learn were the lessons being taught, and that I could learn them just by looking, by watching, by sitting by the Western Wall and daydreaming. From the women of the land of Israel I learned something about how to be alive, even amidst death.

After living in Israel for the past seven years, I cannot idealize it. It is, in so many ways, a hurting, broken society that needs to rebuild from within and without. Still, living there made me, if not a holier person, a wholer one. I never became “more religious” or “more political,” as I think some of my friends and family expected I might. I never developed Jerusalem Syndrome and awoke in the morning thinking I was King David or Jesus (or for that matter, Bathsheba or Mary). And I never imagined we were living in messianic times. Rather, I found a job as an editor and writer at a newspaper, I moved apartments. I made some friends, and when they moved back to the States I made other friends. I got a promotion, the Second Intifada broke out and I heard helicopters overhead while sitting on my porch. The Second Intifada continued and I passed by bombed-out places that I had eaten lunch at the day before, I questioned myself for living there, and felt I was dancing between the raindrops. I grew restless at my job, I got married, I got divorced, my washing machine broke (twice) and the whole bathroom flooded.

Most American Jews who move to Israel don’t do so out of necessity. They’re not fleeing war or persecution or looking for better opportunities for their children. They are idealists to varying degrees: fervent believers who think Israel is the only plot of land on earth where a Jew should live or spiritual seekers looking to explore the alleyways and study houses of Jerusalem, where shopkeepers moonlight as mystics, or self-described atheists, who believe in this strange, mid-century social experiment of building a multicultural society in the sand. Some want to move as far away as they can from their families. Maybe they’re just a little bit crazy, because who else would move halfway across the world to a place that is besieged on all sides, where the language will never be your native tongue, where you will always be an outsider?

The longer I lived in Israel, the more I came to feel an odd mix of belonging and not-belonging. After years of living there, I felt both utterly at home and foreign. Maybe because it was never my goal to fully acculturate into Israeli society, I never did. Most of my friends were Americans and many of the friends I made, even those who planned on staying forever, left. I spoke English at home at work, and even with the Israelis I knew. I did have American friends who immediately adopted the Israeli accent, the Israeli boyfriend, and that particular brand of Israeli impatience – but none of those things ever felt comfortable to me. I took private lessons in Hebrew and went through a period where I forced myself to read a Hebrew newspaper once a week. But I knew the language would never be my own. I was happy in my little English-speaking corner of Jerusalem. But eventually, a part of me came to feel trapped. My world was small and circumscribed, and I started to wonder about all the parts of me that were going unexplored. I hadn’t changed jobs in seven years because good English-speaking jobs are in short supply. I never found a group of writers with whom I could really share my work. I grew tired of everyone around me always talking about God and His books.

So many Americans come to Israel to do their seeking, but I was tired of seeking. I wanted to talk about other things. Living in Israel, I always felt I was part of Jewish history unfolding, but eventually I came to see I wanted to feel my own life unfolding. There was a brief time – maybe a few months – when I thought living in Jerusalem was a panacea. Like all those of various faiths coming on pilgrimage throughout the centuries, I believed I had touched upon something magical and eternal  by being there. I thought I had stepped into that fabled, fantastic reality just beyond the looking glass and that I could claim it for myself. It turned out that living in Jerusalem was, in many ways, a heightened existence, but that didn’t immunize me from the vagaries of life.

by being there. I thought I had stepped into that fabled, fantastic reality just beyond the looking glass and that I could claim it for myself. It turned out that living in Jerusalem was, in many ways, a heightened existence, but that didn’t immunize me from the vagaries of life.

There is no one reason I decided to move back to the States. I cannot exactly explain it to myself even, except to say that I felt I had come to the end of one road of my life. I had been married in the hills surrounding Jerusalem, I had worked in journalism in one of the most heated and volatile times in recent memory, riding the crest of Oslo and its shattered aftermath. I had lived out as much as I could live out there. After almost a decade of living in Jerusalem, I felt I had exhausted its wonders, at least for now.

Now I am back in the place where I grew up, the place where the language is my own, and where my childhood friends are living their lives. I am back in the place where my aunts and uncles and cousins live, where I run into old college classmates on the street. Some of my friends have bought houses or cars or given birth while I was away. At night, when I lie in my bed in my apartment in the city, I close my eyes and remember an entire other life, one where I spent Friday afternoons picking out mangoes and strawberries and oranges in the shuk, where powdered-sugar doughnuts lined bakery windows at Hanukka, and the whole country went camping during Passover. I remember walking home from work as dusk set in on summer nights above the walls of the Old City. There is this other life, just shimmering there. This story I am telling myself is still in the middle of being told. It feels like there are possibilities all around me, even if I am not fully home.

Oh my goodness! Its like you understand my mind! You seem to know a lot about this, just like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with some pictures to drive the content home a bit, besides that, this is outstanding blog. A wonderful read. I will definitely return again.