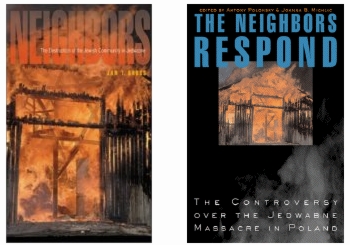

In late May 2000, a slim Polish edition of a work originally published by Princeton University Press – which by all accounts should have remained obscure – was reviewed in the major Polish daily Rzeczpospolita. Its title was simply Neighbors. Written by Polish-Jewish historian and sociologist Jan T. Gross of Princeton, the book’s central thesis – supported in brutal, gut-wrenching detail – was that the murder of Jews in a Northeastern town in Poland called Jedwabne in July 1941 was conducted by Poles, not by the occupying Germans who had instigated it.

In late May 2000, a slim Polish edition of a work originally published by Princeton University Press – which by all accounts should have remained obscure – was reviewed in the major Polish daily Rzeczpospolita. Its title was simply Neighbors. Written by Polish-Jewish historian and sociologist Jan T. Gross of Princeton, the book’s central thesis – supported in brutal, gut-wrenching detail – was that the murder of Jews in a Northeastern town in Poland called Jedwabne in July 1941 was conducted by Poles, not by the occupying Germans who had instigated it.

This was a bold assertion in Poland, challenging the dominant view that only riffraff supported the Nazis and killed Jews, not people who knew and had relationships with them. Of course, nothing sells like controversy. Bookshops could not keep Neighbors on the shelves. A second print run was quickly ordered. While many Poles found the book shocking and offensive, for Jews who have read first-person accounts of Holocaust survivors – not to mentioned those whose loved ones and friends were from Poland and survived the genocide – likely the only shocking and offensive thing about Neighbors was the controversy. I myself had always assumed that collaboration between Poles and Germans during the Holocaust was a foregone conclusion, an idea I could not imagine to be offensive to Polish sensibilities. Ironically, as a result of reading the critique of Gross’ work, which posits a directly opposite view, I have begun to question my own assumptions. But before examining the reasons for this reevaluation, some additional notes on Neighbors are in order.  Situations of Extreme Choice Neighbors generated so much debate that a text edited by Holocaust scholars Antony Polonsky and Joanna B. Michlic entitled The Neighbors Respond was published. The Neighbors Respond – both on its own and in tandem with Neighbors – provided a fascinating forum for Polish and Jewish writers alike. On the level of comparing “facts” of the story of Poland and the Holocaust, it introduced much to be compared and contrasted. For example, Gross placed the number of murdered Jews in Jedwabne at 1,600. A partial exhumation that took place as a result of Neighbors estimated the number of dead at 300-600. (An unfortunate and ironic aspect of the whole controversy was that the exhumation was not completed due to religious concerns raised by rabbis protesting the work). Despite discrepancies in the final tally between Gross’ figure, an incomplete exhumation, and several new testimonies that have recently come to light, Gross has not altered his position. On a deeper level, the books have invited two passionately opposed schools of thought to elaborate on two radically different sets of collective memory. Regardless of the respective backgrounds of the readers, or the conclusions that they now hold, the most interesting result of the controversy is how it models the process by which history comes to be accepted based on the unique, or collective, agendas of historians.

Situations of Extreme Choice Neighbors generated so much debate that a text edited by Holocaust scholars Antony Polonsky and Joanna B. Michlic entitled The Neighbors Respond was published. The Neighbors Respond – both on its own and in tandem with Neighbors – provided a fascinating forum for Polish and Jewish writers alike. On the level of comparing “facts” of the story of Poland and the Holocaust, it introduced much to be compared and contrasted. For example, Gross placed the number of murdered Jews in Jedwabne at 1,600. A partial exhumation that took place as a result of Neighbors estimated the number of dead at 300-600. (An unfortunate and ironic aspect of the whole controversy was that the exhumation was not completed due to religious concerns raised by rabbis protesting the work). Despite discrepancies in the final tally between Gross’ figure, an incomplete exhumation, and several new testimonies that have recently come to light, Gross has not altered his position. On a deeper level, the books have invited two passionately opposed schools of thought to elaborate on two radically different sets of collective memory. Regardless of the respective backgrounds of the readers, or the conclusions that they now hold, the most interesting result of the controversy is how it models the process by which history comes to be accepted based on the unique, or collective, agendas of historians.

For instance, this point was highlighted by Jolanta Zyndul – coordinator of the Mordechaj Anielewicz Center for Research and Education on Jewish History and Culture at the University of Warsaw founded 1990 – in a 2004 edition of Yad Vashem Magazine. Commenting on Holocaust historiography in Poland in general, as well as the Jan Gross controversy specifically, Zyndul explained:

Two years ago, the debate in Poland over Jedwabne – instigated by Jan T. Gross’s Neighbors– facilitated a new critical approach to the [Holocaust]. Until then, Polish research had focused mainly on assistance to Jews in hiding during the war. Today, we are also researching other, less admirable actions of Poles during the Holocaust – blackmailing Jews, informing on them to the German occupants, and even murdering them.

Obviously, the attitude of different societies towards the extermination is one of the most crucial questions in Holocaust historiography. However, in Poland it overshadows all other issues, such as the uniqueness of the Holocaust or its interdependence with modernity. It also lacks – in my opinion as a historian – an approach that portrays it as a universal phenomenon where people face situations of extreme choice. (emphasis added)

The key expression here is the “universal phenomenon where people face situations of extreme choice.” The situation in Poland – the “one of extreme choice” during the war – meant that Poles were viewed with contempt by both Soviet and Nazi occupiers who effectively split the country in half from August 1939 through the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. Jews were, as is all ready well-known, also viewed with contempt. However, the Soviets found political use and offered privilege for a small percentage of Jews who identified themselves as communists. In this way, Nazis and Soviets created a hierarchy that pitted two traditionally rival groups against each other, effectively leading to the genocide estimated at 90 per cent of the Polish Jewish population and 20 per cent of the Polish Christian population. Understanding the function of these hierarchies is critical to understanding the controversy around the work of Gross as a whole.

Poles were treated as an inferior form of human beings to Germans under the Nazis, fit only for annual labor. Meanwhile Jews were not considered human at all. Given the historical context in which Poles were victimized by Nazis, it is easy to understand why Gross’ book, positing Polish-German collaboration as it does, strikes such a sensitive cord. Neighbors countered a hero-victim theme dominant in Polish Holocaust historiography – whereby Poles battled the Nazis and their policies on all fronts – that indeed needed to be challenged. More importantly, it highlighted how the Nazis used artificially created hierarchies to skillfully place one set of oppressed victims over another. A simultaneous status of oppressor and victim is not easy for most people to fathom. The all-too-human tendency to qualify people in wartime situations as heroes and villains, saints and devils, oppressors and victims meant that Poles had to confront the complex, often unpleasant, and often morally repugnant responses their grandparents had had to totalitarianism. Hence, Gross’s slim volume was not only threatening for exposing Polish anti Semitism. It also exposed the essential falseness of moral dichotomies in which people’s actions are only black or white or good or bad without shades of gray in between.

Judeo-Communists In 1939, as mentioned earlier, Germany gained control of the West while the Soviets took over the East. Jews active as communists found opportunities under the new administration unavailable when Poland’s governing National Democratic Party, the Endecja, was in power. Prior to 1939, the only party in Poland that would accept Jews (so long as they were secular) was the communist party. According to Polish scholar Jerzy Jedlicki in The Neighbors Respond, this acceptance was a reversal of the “natural order” in which Christian Poles were traditionally ranked with a status above Jews. This meant that in 1941, when the Eastern half where Jedwabne was located was taken over by Germany, Jews were targeted by Poles and Germans alike.

Though communist Jews (as well as non-communist Jews who were accepted into administrative positions previously unavailable to them) enjoyed certain opportunities under the Soviets, the Soviets themselves were hardly Judeophiles. The newly established Soviet regime almost immediately set out to dismantle organized Jewish religious and political life, and Jews ultimately numbered a third of Soviet deportations. What emerges from a careful, dispassionate reading of The Neighbors Respond – particularly with regard to some of its more sympathetic historians – is a politically and religiously divided Jewish community that would have preferred Soviet rule over the Nazis for obvious reasons, but was confronted nonetheless with a terrible set of choices, none of which offered them any kind of respect or equality. One can be certain that religious Jews, who made up a very large percentage of the Jewish-Polish population – and particularly traditional clergy and Hasidim – would not have supported the adamant secularism of the communists, hating the Soviets only slightly less than the Nazis. Despite this fact, the concept of Zydokomuna, the Polish term for Judeo-Communism, came to define Jews as a whole deep within the Polish psyche. A critique in The Neighbors Respond includes several pieces documenting Jews accused of collaboration with the Soviets, a traditional Polish enemy. What emerges then is one accusation of collective guilt (Jewish-Soviet) against another (Polish-German).

====

The term Zydokomuna was originally introduced in 1817 by Ursyn Niemcewicz in a work entitled The Year 3333. The work posited a future in which a Communist Poland would be run by assimilated Jews. It is not a coincidence that the period when this work was published in the 19th century marked a period in European Jewish history known as the Haskalah, or the Jewish Enlightenment. The Haskalah opened Jews to new areas of knowledge, often freeing them from the traditional constraints of their religious communities. A greater emphasis on literacy amongst Jews relative to their Christian neighbors served as a significant advantage in opening Jews to new professional opportunities. However, old prejudices die hard. Well into the 20th century, Polish political parties, including the ruling Endecja – the National Democratic Party – were fiercely anti Semitic. According to Jedlicki, the more Polish Jews attempted to claim an equal place in society, the more barriers were put in their paths. Anti-Jewish violence actually increased during the interwar period, and campaigns to exclude Jews from universities and certain professions, though not always successful, were a popular example of this trend.

The term Zydokomuna was originally introduced in 1817 by Ursyn Niemcewicz in a work entitled The Year 3333. The work posited a future in which a Communist Poland would be run by assimilated Jews. It is not a coincidence that the period when this work was published in the 19th century marked a period in European Jewish history known as the Haskalah, or the Jewish Enlightenment. The Haskalah opened Jews to new areas of knowledge, often freeing them from the traditional constraints of their religious communities. A greater emphasis on literacy amongst Jews relative to their Christian neighbors served as a significant advantage in opening Jews to new professional opportunities. However, old prejudices die hard. Well into the 20th century, Polish political parties, including the ruling Endecja – the National Democratic Party – were fiercely anti Semitic. According to Jedlicki, the more Polish Jews attempted to claim an equal place in society, the more barriers were put in their paths. Anti-Jewish violence actually increased during the interwar period, and campaigns to exclude Jews from universities and certain professions, though not always successful, were a popular example of this trend.

As mentioned earlier, the communists were the only political party that accepted Jewish members – so long as they gave up their religious views, limiting themselves to a cultural Jewish identity that separated them not only from their religious roots, but often from their families as well. Given how proscribed, constraining, and claustrophobic Jewish life could be, particularly for women, divorce from Jewish roots was a welcome opportunity in many cases. In theory, communism pledged to unite people across ethnic lines through class struggle. Given that the Endecja refused to provide outlets for political activism to Jews, it is easy to see why communism would become compelling for some. Elaborate Nonsense While there were indeed thousands of sympathetic Poles who risked their lives to save Jews, those “thousands” were a significant minority. With a population of 3.3 million, Poland had by far the biggest Jewish population in all of Europe – and in fact in any nation in the entire world – prior to the Holocaust. According to Gross, the economic status of most Jews was “lower middle class.” Though hardly reaching a level resembling the worst anti Semitic stereotypes, the class status that Jews actually occupied ultimately translated to very real material benefits for Polish Christians. Once their neighbors’ houses were left vacant with all of their contents still inside, their Jews former occupants either banished or dead, large numbers of impoverished Poles living under occupation availed themselves to formerly Jewish property quickly and completely.

That the vast majority of Jedwabne’s Jews were killed is not disputed by most Polish historians, nor is the fact that some Poles who had friendly relationships with their Jewish neighbors were involved in the carnage. They accept the repugnance of the slaughter as well. According to Polish historians who dispute Gross’ findings, points of ambiguity include whether or not the majority of Jedwabne’s Jews were killed on that day in July 1941 or during other periods of Nazi occupation, the number of Germans in the city, and the precise role of resident Germans in the slaughter. The results of the partial exhumation suggest another reason for their questioning Gross, as does disagreement about the degree of force Nazis may have used (or not, as Gross insists) in compelling the Christians of Jedwabne to kill Jews

But the issues most worthy of debate, I think, center around methodology – namely the reliability of sources collected fifty years after the fact, an element that Gross ignores but with which other historians agree. These include inconsistencies in the testimonies of the few Jewish survivors after the war ended and Gross’ use of trial transcripts in which the evidence collected from the “alleged” murderers came through beating. Confessions obtained through any use of physical interrogation should rightly be treated with skepticism.

To put it succinctly, there are probably well-grounded reasons for critiquing Gross. Questioning Gross’s historical methodology is not anti Semitic, and Gross himself does not claim it to be. The anti Semitism that creeps into the debate does so as part of the charge of Jewish/Soviet “collaboration,” a defensive charge that is bound to affirm stereotypes of Poles as hateful anti-Semites for Jews and non-Jews alike.

One of the most prominent culprits in this mode of thought is Tomasz Strzembosz, a prominent and respected historian specializing in study of Polish resistance against the Soviets at the Catholic University of Lublin. Strzembosz, whose scholarly focus is the region in which Neighbors takes place, has been criticized for never writing about the murder of Jedwabne Jews or other local towns, even though it is impossible for him not to have known about them. His responses to these critiques have been chillingly hateful diatribes that paint pre-Holocaust Jews as a homogenous population of traitorous, murderous, anti-Polish communists. In his essay “Collaboration Passed over in Silence” from The Neighbors Respond, he writes:

The ‘militias,’ ‘red guards,’ and revolutionary committees’ were the first to cooperate [with the Soviets], and the workers’ guards and citizens’ militias…consisted mainly of Polish Jews. Subsequently, when the Worker-Peasant Militias took control of the situation, Jews were considerably overrepresented in them. Polish Jews… participated in arrests and deportation in large numbers. This was the most extreme example but for Polish Society, the most glaring fact was the large number of Jews in Soviet public offices and institutions – the more so since Poles had been the dominant group before the war.

The essay goes to quote several sources ranging from diaries to articles written by a wide range of people – including journalists, a nun, and others highlighting the take-over of public institutions by Jews. He also describes Jewish participation in ugly events, including killings and deportations. Seizing upon a source used by Gross in one of his Polish-language essays, he quotes remarks made by Jews to Poles: “You wanted a Poland without Jews, now you have Jews without Poland.” The essay crosses into the realm of the disturbing and the bizarre with the following passage:

Indeed, Jews may have not had things too good in pre-war Poland…However they were not deported to Siberia; they were not shot or sent to concentration camps; they were not deported to Siberia, they were not killed through starvation and hard labor. If they did not regard Poland as their homeland, they did not have to join its mortal enemy in killing Polish soldiers and murdering Polish civilians.

But the truly revolting statement comes with the following:

Did the Polish inhabitants of Jedwabne and the surrounding villages enthusiastically welcome the German as saviors? Yes, they did! If someone pulls me out a of a blazing house, I will embrace and thank that person. Even if the next day, I regard him as yet another mortal enemy

Tellingly, throughout his polemic there is no examination of statistics regarding Jewish involvement in communism, or communism in Polish society as a whole. There is no discussion of demographics in terms of religious practice among Jews, including Hasidim, whose religiosity would have placed them in opposition to the communists. Nor is there any speculation about how the Polish view of Germans as “saviors” – to use his term – would have driven wedges between Christians and Jews in regions that the Soviets were dominating, including Jedwabne.  Jedwabne’s inhabitants were trapped under Soviet occupation in 1939, then German occupation in 1941. The murders that took place were clearly ones in which Jews were marked as supporters of the Soviets. The question of whether or not Jews were communists per se or simply unsupportive of the Germans remains unanswerable, as well as an open debate. The murders in Jedwabne included several devout Jews, including the cheder instructors and the kosher butcher, whose religious beliefs could not have corresponded with communism, a subtlety that escapes Strzembosz. In a time of extreme insecurity, the latter could likely be mistaken for the former. However, as Gross shows, Zydokomuna was certainly an element of the hatred. In Neighbors, an elderly woman testifies:

Jedwabne’s inhabitants were trapped under Soviet occupation in 1939, then German occupation in 1941. The murders that took place were clearly ones in which Jews were marked as supporters of the Soviets. The question of whether or not Jews were communists per se or simply unsupportive of the Germans remains unanswerable, as well as an open debate. The murders in Jedwabne included several devout Jews, including the cheder instructors and the kosher butcher, whose religious beliefs could not have corresponded with communism, a subtlety that escapes Strzembosz. In a time of extreme insecurity, the latter could likely be mistaken for the former. However, as Gross shows, Zydokomuna was certainly an element of the hatred. In Neighbors, an elderly woman testifies:

I saw how they ordered young Jewish boys to take off Lenin’s monument, how they were told to carry it around and shout, ‘War is because of us.’ I saw how they were beaten at the time with rubber truncheons, how Jews were massacred in the synagogue, and how the massacred Lewiniuk, who was still breathing, was buried alive by our people.

Gross describes how Jews were knifed, drowned, dismembered, and buried alive in ruthless, unsparing detail. A pregnant Jewish woman had her abdomen ripped open by the Gentile farm-hand of her father. A little girl’s head was sawed off and kicked like a soccer ball. Jewish women were raped. Tellingly, one of the Jewabne Jews who was offered amnesty for hiding a Polish army officer from being kidnapped by the Soviets refusing it, choosing instead to die with the rest of the Jewish community. Of course, Jews were killed in these very same ways by Germans and Soviets alike.

In a roundtable discussion in which Strzembosz and Gross took part, Gross stated:

Between one fourth and one third of the deported civilians [under the Soviets] were Jews. Your article says, ‘The Poles are persecuted by the Jews; the Jews sent them to God knows where.’ Well, it was not like that. The Jews suffered just as much as everyone else under the Soviet occupation, if not more. The whole stereotype of Jews supporting the Bolsheviks and Communists is nonsense.

Strzembosz’s response:

The problem arises when the Jews flee from the Lublin region across the San River but are greeted with machine gun fire. They choose the Soviet Union but the Soviet Union does not want them…If the Jews collaborate with the Soviets, and I know of several such cases, and are subsequently sent into the depths of the USSR, it does not mean that they are merely victims and never executioners…

But what troubles is not the triumphal arches but the fact that in sixteen in places in so-called Western Belarus, Jews open-fired on Poles. That is why information about 30, 40, or 5 percent of the Jews being deported is no answer to the question about the extent of their collaborations with the occupation regime. (emphasis added)

====

Strzembosz’s description of the repugnant and violent actions of some Jewish communists under Soviet occupation would not necessarily be offensive if he placed them under a larger historical context that, besides recognizing the rock-and-hard-place in which Jews found themselves politically, also acknowledged that a pre-Holocaust Polish Jewish population of 3.3 million would be comprised of factions whose politics and relations to Soviets varied widely. Throughout The Neighbors Respond, whether the commentator is Strzembosz or Cardinal Jozef Glemp – the primate of Poland infamously known for his construction of huge crosses as Auschwitz – the charge of “pro-Bolshevik attitudes” arises over and over again.

Strzembosz’s description of the repugnant and violent actions of some Jewish communists under Soviet occupation would not necessarily be offensive if he placed them under a larger historical context that, besides recognizing the rock-and-hard-place in which Jews found themselves politically, also acknowledged that a pre-Holocaust Polish Jewish population of 3.3 million would be comprised of factions whose politics and relations to Soviets varied widely. Throughout The Neighbors Respond, whether the commentator is Strzembosz or Cardinal Jozef Glemp – the primate of Poland infamously known for his construction of huge crosses as Auschwitz – the charge of “pro-Bolshevik attitudes” arises over and over again.

Glemp’s and Strzembosz’s ignorance, though not justifiable, is perhaps understandable when one considers that they are living in a country in which “anti-Zionist” purges of the late sixties from academia and government sent 35,000-40,000 of Poland’s remaining Jews packing. The constrained environment in which academics, journalists, and writers were living since the end of World War II would make it very difficult for controversial ideas of any type to be aired, but what of the following statement by George Steiner in his overall positive review of Neighbors in The Guardian Weekly:

The current primate of Poland, Cardinal Jozef Glemp, has made no secret whatsoever of his distaste for Jews… To this must be added the Polish conviction, not altogether unjustified, that Jewish intellectuals countenanced and were, though briefly, participant in the coming of Marxist and Soviet Despotism.

Hence, Jews in the annals of historiography, even in the pages of a progressive, respected British left-wing weekly, come up against the exact same charge. Even if one questions some of Gross’s assertions and methodologies, as indeed I do, having to read about Jewish-Soviet collaboration again and again is grating. The Polish Jewish population was too large to be homogenous with any ideology, including communism, which on the whole was marginal in pre-Holocaust Polish society.

Fear and Loathing in Poland In Gross’s recently published book Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz, he deals head-on with zydokommuna or “Judeo-Communism.” Zydokommuna is, in fact, the title of the sixth chapter. There is a sense of urgency in Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz, in which Gross wants to dispel, once and for all, the myth of Jewish/Soviet collaboration. Given that the accusations come from respected historians, a revered cardinal, and finally a book reviewer in The Guardian, it is understandable why.

Quoting sociologist, Jaff Schatz, Gross places the number of communists in Poland as ranging between 20,000-40,000. By electoral count, communists number 1.5 per cent in 1922, 4.1 per cent in 1928, and back down to 2.5 during 1930. Based on numerical data from the 1930s, culled by the same sociologist, Gross puts the number of Jews involved in communist groups as “22 to 26 per cent” of communists as a whole, approximately 7,500 Jews at the most. This means Jewish communists consisted of approximately 1/5 of one per cent of the Jewish community as a whole. While it is true that Jews occupied certain positions of authority among communists due their higher education – maintaining seat in the central committee and the party “teknika, the apparatus for production and distribution of propaganda materials” – this particular demographic of highly literate in that particular department might well have inflated Jewish numbers among communists in the Polish imagination.

I question Gross’s proposition that the number of Jewish communists were this low, simply because there is so much literature on Jewish involvement in the left-wing activities of the day. Besides mainstream Communist movements in which Jews could participate, there were the Bund, a secular Jewish labor movement which emphasized Yiddish culture as well as socialists as well as the Labor Zionists combining Zionism and socialism. There was also notable Jewish involvement amongst anarchists. Whether Gross is correct or not about how he interprets these numbers, it is important to note that the most vocal proponent of Jewish-Soviet collaboration, Tomasz Strembosz (and Gross’ main academic opponent), never quotes statistics at all, never considers demographics, and never quotes studies about how many people voted for communists. Instead, he constitutes his methodology by relying on diaries and letters colored by anti Semitic prejudices that kept Jews out of civil administration for years. If, according to several Polish historians, Gross’s methodology needs to be placed under a magnifying glass, the same thing undoubtedly needs to be said for Strembosz as well.

As for post-war Poland, Polish historians rightly state there were some communists of Jewish origin who behaved viciously. In addition, there is a stormy sea of irreconcilable and contradictory studies available on Jewish involvement in post-war Poland. After wading through the dizzying array of statistics of communist involvement by ethnicity – which after the Holocaust numbers at most a few hundred Jews within many tens of thousands – Gross concludes, rightly, that the activity in which he himself is engaging is nothing more than “a numbers game,” one he is forced to play due to the loud and consistent charges of Judeo-Communism. Given that the pre-Holocaust Jewish population reached over three million people, the number of Jewish communists in post-war Poland’s “apparatus of oppression” means nothing. Perhaps that’s the reason for choosing as one of his epigraphs a quote from Hannah Arendt to open Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz:

Thus, prima facie, all this looks like elaborate nonsense, but when many people, without having been manipulated, begin to talk nonsense, and if intelligent people are among them, there is usually more involved than just nonsense.

The overall subject of the Fear, as its subtitle makes clear, is post-war anti-Jewish hatred, the expressions of which were as follows: the refusal of the courts to hear complaints brought forth by Jews attempting to repossess property; the beatings of Jews as well as non-Jews mistaken for Jews on trains; the torment of Jewish students in public schools; fear of retribution and violence experienced by Christian Poles (by their non-Jewish neighbors) who had hidden Jews, including children; and pogroms in cities such as Kielce in which the alleged charge was ritual murder – hearkening back to the medieval era in which claims that the blood of Christian children was used for making matzah were popular. Through it all, communists were for the most part indifferent, believing that taking a stance against anti-Semitism would be politically isolating. Many Catholic priests defended or did not speak out against the charge of ritual murder.

The overall subject of the Fear, as its subtitle makes clear, is post-war anti-Jewish hatred, the expressions of which were as follows: the refusal of the courts to hear complaints brought forth by Jews attempting to repossess property; the beatings of Jews as well as non-Jews mistaken for Jews on trains; the torment of Jewish students in public schools; fear of retribution and violence experienced by Christian Poles (by their non-Jewish neighbors) who had hidden Jews, including children; and pogroms in cities such as Kielce in which the alleged charge was ritual murder – hearkening back to the medieval era in which claims that the blood of Christian children was used for making matzah were popular. Through it all, communists were for the most part indifferent, believing that taking a stance against anti-Semitism would be politically isolating. Many Catholic priests defended or did not speak out against the charge of ritual murder.

The ultimate irony was that in Kielce, after the post-Holocaust Jewish population left in fear for their lives, local Christians helped themselves to leftover foodstuffs in a building that had housed Jews. This food included matzah. A woman who lived next door to the building remarked in an interview on how good it tasted. The filmmaker asked her:

‘And what about the blood of Christian children that people believed Jews were using to produce matzoh.’ The lady smiled again with a chuckle.

Thus, for Gross, the blood libels, as well as the charge of Judeo-Communism, are nothing more than excuses, cover-ups for the shame that many Poles felt in either collaborating actively with Nazis, or standing by and letting it happen. In the end, the full number of Jews killed after the Holocaust in Poland was 500-1500. Gross concludes that:

The Jews who survived the war were not threatening just because they had availed themselves of Jewish property that its rightful owners might come back to claim it. They also induced fear in people by reminding them of the fragility of their own existence, of the propensity of violence residing in their own communities, and of their own helplessness vis-a-vis the agents of pseudospeciation who now invoked class criteria for elimination from public life.

The Fragility of Memory and Moral Behavior Fear is a much better book than Neighbors. The latter, which does not truly explore the relationships between Jews and Christians in Jedwabne as they changed under Soviet and German occupation, is somewhat flat and two-dimensional. In contrast, Fear is psychologically penetrating, asking and attempting to answer more complicated and disturbing questions about the “moral economy” of a people, the Poles, during a period in which they too lost a great deal, particularly in human resources through the murder and deportation of intelligentsia, clergy, and lawyers, as well as economically.

A fair and final analysis must conclude that in totalitarian societies hierarchical layers or strata are constructed essentially to pit victimized groups against each another. As in Jane Goodall’s studies on a “civil war” amongst wild chimpanzees, Gross is describing “pseudospeciation.” The Nazis and the Soviets exploited rivalries and prejudices by conferring crumbs of privilege and benefit to particular parties that they preferred over others though still viewing their “favorites” with contempt. Nazis did that the same for the Poles by letting them claim Jewish property. Soviets did so by allowing a select group of Jews employment opportunities previously unavailable to them in civil institutions. In both cases, blood was still spilled among the so-called privileged groups, marking the term “collaboration,” be it Polish-German or Soviet-Jewish, appear ever more simplistic and unfair.

In the midst of all of this controversy, one anecdote in Fear stands out, in which a Polish woman, a maid, hides her former employer’s Jewish children in a village just outside of Cracow. Forced to bribe neighbors who would gladly snitch on her and see the children killed, she devises an ingenious plan to save the children whom she loves as her own.

I put the children on a cart, and I told everybody that I was taking them out to drown them. I rode around the village, and everybody saw me and they believed, and when the night came, I returned with the children…

If those in the village who were not committing ugly acts of extortion sided with the woman they would still – with good reason – fear that the entire village could be burned by the Nazis as a form of reprisal, an event that would kill even more people, including children. This is one reason why people pressured her to give up the Jewish children she was hiding. Gross’s version of what happened in Jedwabne may have rankled Polish readers; however, I cannot help but wonder if it was the following passage that was the real slap in the face for many Poles:

…we are left with a frightening realization that the population of a little village near Cracow sighed with relief only after its inhabitants were persuaded that one of their neighbors had murdered two small Jewish children.

In such situations, there are very few people, regardless of religious or ethnic background, who can maintain the high level of bravery evident in this woman. Her action did not just save two Jewish children, but potentially an entire Polish village on which the Nazis might have enacted collective punishment. The difficulties faced by everyone in the village do not mean it would have been right to sacrifice the two Jewish children, but ultimately show the kind of impossible moral choices that Poles had to make, even while many did indeed take advantage of their situation.

This point does deny that some or perhaps most of the villagers were guided by anti Semitism. However, given the situation in which they found themselves, and as emotionally difficult as recognition of it may be for many of us who are Jews, perhaps we should allow a little bit of room to ask what most people, regardless of religious or ethnic background – including Jews – might do in the same or a similar situation. While I sympathize with many of Gross’s ideas, and am awed by (and grateful for) the systematic way he dismantles the “elaborate nonsense” behind Zydokomuna, some of his moral pronouncements in Neighbors, like the one above, are a little too neat to capture the climate of fear during the period described.

This said, it becomes all too clear in Fearthe reasons why Jewish survivors and Poles who helped Jews were (and are) such threats to the collective memories of all of the communities involved. As Gross eloquently and brilliantly proves, they have reminded the majority of Poles of the fragility of their own moral behavior. Meanwhile, the “Righteous among Nations” in Poland – Poles who hid Jews like the woman above – did something extraordinary beyond defying the Nazis. They saw through the artificially created strata of “pseudospeciation” – joint Nazi-Soviet oppression – and let their humanity shine through. Without using the term “elaborate nonsense,” they recognized “elaborate nonsense.” And regardless of our respective religious and ethnic backgrounds, there are precious few of us who do that. This constitutes the real lesson within the controversy engendered by Gross’ work, not who collaborated with whom.

This site can be a walk-through its the information you wanted concerning this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll undoubtedly discover it.

The actual difficulty note is certainly you are able to JUST take a look at the actual standing on your taxes reclaim via the internet by looking to the actual IRS . GOV web site.

i am very picky about baby toys, so i always choose the best ones.,

very nice post, i undoubtedly enjoy this excellent website, continue it

fantastic issues altogether, you simply won a logo reader. What would you suggest about your put up that you just made a few days ago? Any positive?