1. Gay/Not Gay

1. Gay/Not Gay

Well, it happened again. Another journalist has covered Zeek, and has singled out homosexuality as an important, even central, theme of this magazine. It is not. But this mistake has happened so many times that I think it has something important to say about homophobia and difference.

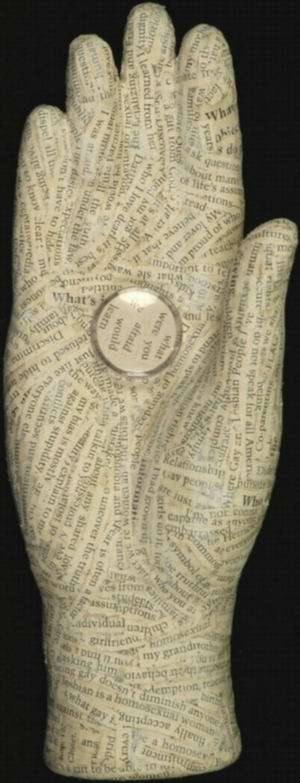

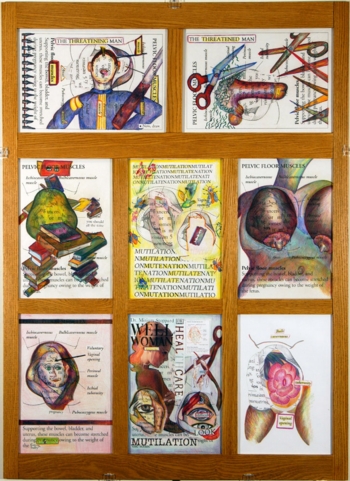

First, the facts. Zeek is not a gay magazine. It is not a queer magazine. It has two gay editors on a staff of fifteen. I am one of them. Does Zeek run a lot of content about gay people, queerness, or homosexuality? Actually, no. In fact, a review of all of the pieces we’ve run over the last five years revealed that less than 2% of our material addresses themes of homosexuality – or even sexuality in general. We are proud to have featured an expose of the shocking practice of “conversion therapy” being peddled in the Jewish community, and brilliant first-person essays by transgendered Jews and queer Jews of a variety of backgrounds. But, we are sorry to say, these voices remain statistically under-represented at Zeek.

And yet, Zeek is routinely called a “gay magazine.”

For example, in a recent profile of Jewish magazines, the one sentence allotted to Zeek, which was founded five years ago and co-invented the “New Jewish Culture” that sociologists are now writing about, said that “The most recent issue of Zeek, a highbrow journal of essays, art and literature, features the musings of a newly religious gay man in Jerusalem.” That’s it. In fact, the “musings” the reporter was referring to was actually a 5,000-word essay reporting, first-hand, on the underground community of Orthodox gay men trying desperately to change their sexuality, meeting furtively to “support” one another in their tragic and futile efforts. But how peculiar that this one article is what was chosen to describe what we do.

Other examples: in 2004, Zeek was referred to as a “gay youth magazine” (Reform Judaism, 2004). Last month, at the Koret Jewish Book Awards, where a Zeek intern was passing out free copies of our print edition, someone told him “interesting, a gay Jewish magazine.” Last year, a noted rabbi who wrote an essay for the magazine said, “what you’re doing is great. Of course, I’m not gay.”

And there are countless other examples. What’s going on? 2. Gay is the New Black

Clearly, in our cultural moment in America and in the Jewish community, sexuality is newsworthy. The struggle for equality for members of sexual minorities is the signal civil rights struggle of our time, for a variety of reasons which I’ve written about elsewhere. And in the Jewish community, acceptance of sexual minorities is fast replacing gender egalitarianism as the key dividing line between progressive and non-progressive Judaisms. In the last two months alone, homosexuality has made headline news in the Jewish community on three distinct occasions: the Jerusalem Pride march, the Israeli Supreme Court’s decision that Israel must respect foreign marriages regardless of the genders of the two parties, and the Conservative Movement’s latest decisions on the halachic status of homosexuality. To put it glibly, and in a nice “Queer Eye” fashion metaphor, gay is the new black. So perhaps Zeek’s “gayness” stands out more than the 1.5% it should, because gayness stands out in general.

Gay is also me. I’ve been an outspoken advocate of equality for GLBT people, and have been published widely on these issues, and although I am only one on a large editorial staff, I am the editor in chief, and so maybe my public stance regarding equality for sexual minorities has rubbed off on Zeek. In fact, I can’t help but wonder whether my own sexuality, which is supposed to be no big deal, is holding this magazine back, limiting its appeal and reducing what it is about. And that makes me both sad and angry.

Primarily, though, the “Zeek is Gay” riff that sexual diversity is still not normal. We can talk all we want about acceptance, but being gay is still unusual. Years ago, when I was a corporate lawyer, I heard people refer to African-American lawyers as “black lawyers” and female lawyers as “lady lawyers.” (This last in Florida, in the 1980s.) Zeek being a “gay magazine” is similar. Now, if Zeek really did feature a lot of gay-themed content, the mistake would be understandable. After all, this is how the mind works: it looks for what’s different, and notices that. But Zeek doesn’t feature a lot of gay-themed content. Apparently a miniscule amount, and perhaps one part-time activist as a chief editor, is enough.

3. Jewish is the New Gay

Ironically, “Zeek is Gay” is actually a perverse reflection of some of the guiding principles of this magazine. When we started this enterprise five years ago, we wanted a place where we wouldn’t have to closet our identities… our Jewish identities, that is. We were frustrated that the leading venues of new writing in America, places like the New Yorker, or TNR, or Salon (at the time), were heavily populated by Jews, but that their Jewishness was overwhelmingly a closeted and unreflective affair. Here were brilliant, insightful writers who had sophisticated views and sharp pens, and yet when it came to Judaism, they had all the subtlety (and pride) of a rebellious 14-year-old. Which makes sense if that’s where your Jewish education ends — but which hardly does justice either to the manifold forms of Jewishness or to the talents of writers and editors.

We at Zeek didn’t want to be in the closet, and so we came out as a Jewish journal. We were not a journal of Jewish culture, covering the latest Jewish this or that, but we were a Jewish journal of culture, covering the subjects we found interesting with our Jewishness out, loud, and proud. We didn’t want to segment our Judaism and our commitment to cultural excellence. And we were tired of so much “Jewish culture” really being a form of advertising, just another tool to get you to meet and mate with other Jews.  Well, it worked. We have up to a hundred thousand readers a month, and on a budget less than 10% of some of our recent competitors, we’ve made our mark. Naturally, no one in the non-Jewish press (i.e., the other 99% of the world) has called us a gay magazine. For them, our Jewishness is what sticks out like a sore thumb — and we’re fine with that. We’re going to keep on featuring the best new Jewish writing and art, and we’re going to keep wrestling with issues that are edgy, controversial, and occasionally inspiring. After five years, we’re certainly not going back into the Jewish closet.

Well, it worked. We have up to a hundred thousand readers a month, and on a budget less than 10% of some of our recent competitors, we’ve made our mark. Naturally, no one in the non-Jewish press (i.e., the other 99% of the world) has called us a gay magazine. For them, our Jewishness is what sticks out like a sore thumb — and we’re fine with that. We’re going to keep on featuring the best new Jewish writing and art, and we’re going to keep wrestling with issues that are edgy, controversial, and occasionally inspiring. After five years, we’re certainly not going back into the Jewish closet.

In the queer theory world, it’s increasingly understood that Jewishness and queerness are similar species of Otherness. Both Jews and queers are “different,” yet, unlike most African-Americans, say, both gay people and Jewish people can “pass” in the majority culture. Thus, Jewishness and queerness is a form of difference, but one that can be concealed and disclosed as one wishes. Jews and queers are also ubiquitous, found in all corners of society — clustered in urban centers, yes, but also found in far-flung places around the globe. There are Jewish travel guides and gay travel guides, Jewish in-jokes and gay in-jokes, and, yes, Jewish magazines and gay magazines. And while Jews and queers each forms a single, distinct subculture when viewed from the outside, both communities, from the inside, are really made up of quite diverse and often-warring factions. This is less obvious in the GLBT community than in the Jewish one, but you won’t find a Queer Nation post-gender hipster and a buff Chelsea/Castro boy together any more often than you would a Reform Jew and an Orthodox one.

In large part, the recent “New Jewish Culture” has been to Jewishness what the last decade of gay culture has been to the GLBT world. The timelines are different — Jews had their Holocaust in the 1940s, gays the AIDS plague of the 1980s, and while Jewishness became basically OK in the 1950s and 1960s, being gay is still not OK in many places today. But the parallels are nonetheless instructive. Just as the last ten years have seen a remarkable opening to gays and lesbians in American society, so too have the last few years of “New Jewish Culture” largely been about celebrating Jewish difference, rather than the rush to assimilation. Sometimes this manifests merely in a superficial delight in kitsch, but other times it has a lot to do with no longer being embarrassed to be Jewish – or rather, being quite embarrassed about Jewish culture’s neuroses but also very eager to share, ridicule, and explore them with the world. Hence Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and Jewtopia, right alongside Jim McGreevey and Joe Lieberman.

Jewishness and queerness are also quite alike in the contentious nature of their difference. Many lesbians, gays, and Jews would like nothing more than to erase difference and be completely normal. For them, America is the land of opportunity precisely because it offers the possibility of erasure. Indeed, Jews can assimilate even more readily than gays, either embracing Christianity as a religion or so imitating its exterior trappings that the Chanukah bush and the Christmas tree blend into one. And intermarriage is far less visible than Heather having two mommies.

Yet for “committed” Jews, assimilation is a terrible thing, signifying loss of heritage, loss of tribe, and so on. In the Jewish community, there is often outright hostility toward those who choose to assimilate, or intermarry, as if only one choice about Jewish culture is at all defensible. In the gay community, there seems to be a bit more tolerance — maybe gay people still have more of a memory of being persecuted than Jewish people do. Or, more likely, maybe they respond to that persecution in diametrically opposed ways, supporting more freedom, rather than more fidelity to the group.

(Of course, many anti-assimilationist Jews are pro-assimilationist when it comes to sexuality, going so far as to wish that homosexuality wouldn’t exist at all. It is always amazing to me to come across these people. Do they really think that Jewishness, in a Christian context, is any more defensible than homosexuality in a Jewish one? Surely it’s less defensible, because it’s far easier to change one’s religion than change one’s sexuality – I can’t help being gay, but I can help being Jewish. So it goes.)

Well, Zeek has made its choice. We’re not gay, but we are out. It’s not always an easy choice; the Jewish community is small, and bickers a lot. Most of us on staff have careers in the wider world, where being “too Jewish” is a handicap, and where temporary assimilation is a worthwhile exchange for more excellence, a bigger audience, and a broader cultural palette. Maybe it’s the bitterness of that experience that makes being “too gay” all the more insulting.

Still, in the end, I’m glad we’re not in the closet. I get uncomfortable when I’m asked to hide part of myself, especially in my writing, even though doing so might lead to a wider readership and more money in the bank. And I do think that there is much to celebrate in Jewish culture and spirituality – not as a tool to convince Jews to mate with one another, but for its own sake, because it poses interesting questions and wrestles with the answers.

Naturally, some of those questions relate to issues of sexuality and identity, and so we’ve devoted about 1.8% of these pages to dealing with those issues. Apparently that’s too much for some. But if we put our sexualities in the closet, can our Jewishness be far behind?

When visiting blogs. i always look for a very nice content like yours “

Regards for this tremendous post, I am glad I noticed this site on yahoo.

I’m new to your blog and i really appreciate the nice posts and great layout.”*~;;

It indeed does take quite some time to find great information like this. Thank you very much.

I simply wished to appreciate you again. I do not know the things I could possibly have taken care of in the absence of those aspects discussed by you concerning that area. Completely was the depressing condition in my position, but seeing a new specialized strategy you solved it made me to leap for delight. I’m grateful for the work and even hope that you recognize what a powerful job your are putting in teaching people today through a web site. Probably you’ve never got to know all of us.

Johnny Depp is my idol. such an amazing guy ..