"Everything is foreseen; yet free will is given" – Pirkei Avot 3:15

Much of Western ethics, religious and secular, seems to rely on the concept of "free will," the principle that each of us is free to choose – in both mundane and morally significant contexts – and thus bears responsibility for whatever choice we make. Choose to indulge your urge to steal, and you bear both moral and legal responsibility for the consequences of that action (particularly if you get caught). And so on.

This notwithstanding the withering attack on free will by scores of philosophers. John Locke and David Hume called it nonsensical. Schopenhauer, whose philosophical work is largely about the question of will, noted it is only an a priori perception, not an actual description of events. As Hobbes noted, free will has only apparent reality; in Nietzschean terms, it has conventional truth only; in terms of absolute truth, it is incoherent.

This notwithstanding the withering attack on free will by scores of philosophers. John Locke and David Hume called it nonsensical. Schopenhauer, whose philosophical work is largely about the question of will, noted it is only an a priori perception, not an actual description of events. As Hobbes noted, free will has only apparent reality; in Nietzschean terms, it has conventional truth only; in terms of absolute truth, it is incoherent.

Ultimately, "free will" is useful solely for describing our perception of, and responsibility for, decisions. This is enough: in the classic compatibilist perspective, it is coherent as a mental phenomenon, even if it makes no sense absolutely – and yet since its only function is as a description of a mental phenomenon, no more is required.

However, particularly in the Jewish religious world, this absurd notion that we actually somehow have free will, really, as a matter of ontology, persists – and it persists to justify an entire system of incoherent egotism which resolutely opposes every effort to liberate the self from the ego. As an agreed-upon ethical convention, free will is as useful as it is obvious. As a metaphysical proposition, however, it is more an obstacle to moral and spiritual self-fulfillment than an aid.

1. I dare you to defy your conditions

First, the observable facts. The meaning of "free will" is essentially that there exists an action without any external causes, solely determined by an independent moral agent who, while of course affected by the world, ultimately operates independent of it. The notion is that there is a "me" making decisions, freely choosing, and solely accountable.

Free will is really a subset of the classic philosophical distinction between determinism and indeterminism. Normally, of course, most of us live our lives according to determinism. We expect that when we are ill, there is a cause (material or otherwise) of the illness; that when we see cars, they likely have drivers (and engines); that rain does not materialize out of nothing in the sky. All phenomena have causes; they do not blip in and out of existence on their own. (The pseudo-quantum-mechanics objection to this point is discussed below.)

Yet most of us live our ethical lives according to indeterminism. We assume that we make choices, and that those choices are "ours," that is, not wholly caused by other things. The buck stops here. At this moment, you could continue reading, or click to another page – and of course it seems that the choice is yours. However, simply relying (for the moment) on the empirical data of one’s own thought process, this is clearly not what is actually going on. Both logically and empirically, whatever choice you make is completely – not mostly, or partly, but wholly – caused by the sum total of causes and conditions which have brought you to the moment of choice. Where else would it come from? Some of these causes may be proximate – how interesting this essay is, how restless you are, what you have to do in five minutes – and others may be quite distant: how you respond to philosophizing; your gender, race, and class; and so on. It is beyond our ken to identify all these different causes and conditions, but surely they exist. Even if a choice seems totally impulsive, even random, it is caused by something, is it not? And whatever that something is – or rather, whatever the uncountable myriad of somethings are – already exist(s) as the product of other causes and conditions. Indeed, even the choice to say, exactly, "I defy my conditions!" can, of course, be ascribed to various conditions. Sorry. (Religiously speaking, it’s one of the catches of an omnipresent, Infinite Being – there’s no getting away from It. But we’ll get to religion later.)

This is observable through meditation, which, contrary to its various associations with all forms of spiritual nonsense, is as close to the scientific method as the introspective mind can get. There’s a tendency to say to meditators "well, that’s your experience," as if scientific observation is indistinguishable from taste. But meditation, in this sense, is not about having an "experience;" it is about observing closely the patterns of mind. (Again, not the brain – just the mind, for now.) Likewise, its results are not "my experience" any more than the results of an observed scientific experiment are "my experience." If you want to repeat the experiment, get trained, sit down, and follow the same process. The process of meditation is to slow down the rapid-fire to an extent that the mechanism of causation and choice can be seen more clearly. Involuntary actions which ordinarily pass unnoticed are seen as intricately detailed sequences of desire and repulsion. Just brushing away a mosquito can seem like a choreographed ballet.

And what everyone who follows this process reports is that, like a seemingly continuous motion picture revealing itself to be, when slowed down enough, a chain of rapid-fire images, so too the mind. Whereas normally it seems like "I make a decision," in clear enough meditative states, it’s possible to actually observe how the different actions and reactions which usually get labeled as "the self" are evoked when the right conditions are present, how habituated responses dictate action, and how even in instances of choice, the thought processes one goes through are caused by personality, environment, and the rest. Once more – not feel, not intuit, not "experience," but actually observe the component parts in motion. The smooth clockwork of discursive thought is deliberately interrupted in such contexts, and its mechanistic nature can be observed. There is no self driving the gears – the self is the gears. It’s an emergent phenomenon of the uncountable causes and conditions that are happening all the time.

This is what can be observed empirically, on the phenomenal level of the mind. In itself, it is still insufficient, because one might argue that while it seems to the meditator that her thoughts are occurring in this piecemeal way, in fact, contrary to her observations (and to the centuries of recorded observations of others who have devoted their entire lives to fine-tuning their perceptive apparatus), there is still some "self" which spontaneously and without cause generates thoughts, decisions, and actions. Weird, and unjustified, but still possible.

Most determinists, then, usually move from experience either to formal logic or to the principle popularly known as "Occam’s Razor" – that "all things being equal, the simplest solution tends to be the best one." Certainly, the latter strongly mitigates against the anti-determinist position. If we can fully account for the phenomenon of the thinking mind within the bounds of (a) known scientific laws and (b) the observed experience of mind without (c) inventing a non-material, invisible ghost in the machine, then surely it seems more rational to do so. I mean, it’s how we operate all the time, right – if the rainfall can be explained wholly by climatology, we don’t presume the existence of angels and demons who are running the weather. So why do so in connection with the "soul"? Simply because it makes us feel better?

But Occam’s Razor, too, is not necessarily right. After all, there could be some weird, somehow non-caused self, even if it’s a complete departure from how we ordinarily interpret the events of the world, even if it flatly contradicts the direct, reported experience of people who spend decades closely observing the mind, and even if it requires the supposition of not just one angel or demon but an entire dimension of non-materiality… right?

Wrong.

The non-material soul is a concept which dates back at least to Plato, although its modern conception is primarily the work of Descartes. Bashing Descartes seems to be all the rage in recent years, which is a pity, but perhaps on this one point I might join in the chorus. Descartes famous dualism – that the world is composed of matter and spirit – allows for the self to be real, independent, and possessed of free will; it is totally untouched by the vicissitudes of material causation. But it left him in a bit of a quandary. If the spirit is totally separate from the material world, how does it influence it? Somehow, my "spiritual" desire to move my hands is causing my fingers to type – but how?

Famously, Descartes suggested that there is a nexus between the material and the non-material in the pineal gland of the brain. Given what we now know about the pineal gland and its role in consciousness, that Descartes chose it is quite remarkable, even prescient. But even electricity and the various energies of the brain are still material. The question is one of principle: how can something totally disconnected from materiality have an effect on the material world? It just doesn’t make sense – it didn’t to Descartes, and it hasn’t for centuries since.

Lately, Descartes has had an unexpected and preposterous ally: quantum theory. In recent years, pseudo-scientific religious discourse has seized on the apparent conclusion of quantum mechanics that subatomic particles can indeed appear and disappear uncaused. As popularized in the delightfully trippy but scientifically unsound film What the Bleep Do We Know?, the notion is that free will somehow emerges from this capacity of the universe for uncaused randomness. Perhaps the soul, some non-material essence of the human self, is able to pop gluons and mesons into existence, and from there, somehow, an independent consciousness influences the material brain.

Well, this is balderdash, in terms of physics. As minute as neurons are, they are gargantuan in size compared to subatomic particles blinking in and out of existence, and every thought we have is really a phenomenon caused by many neural connections, in different parts of the brain. Suggesting that quantum flux influences the brain is like saying that an ant crawling across my floor suddenly built my home.

All this quantum bullshit (Ken Wilber’s Quantum Questions is a terrific anthology of the 20th century masters of quantum theory all lining up to say that, while it is remarkable, mystical, and amazing, it has nothing whatsoever to do with "thoughts creating reality" or free will or anything like What the Bleep suggests) just exists to somehow justify an intuitional sense of the world which is flatly contradictory (material influenced by non-material!), directly disprovable (through meditation and introspection), and is only around at all because it seems to feel good.

But notice what this explanation is attempting to provide: a way out of materiality and causality. That’s the enemy – and yet, as I’ll show in the next part, it’s really our best friend. It’s enlightenment itself. It’s the answer. Ironic, isn’t it – that it’s precisely the "spiritual" people who are most loudly pushing the antithesis of spiritual realization?

But notice what this explanation is attempting to provide: a way out of materiality and causality. That’s the enemy – and yet, as I’ll show in the next part, it’s really our best friend. It’s enlightenment itself. It’s the answer. Ironic, isn’t it – that it’s precisely the "spiritual" people who are most loudly pushing the antithesis of spiritual realization?

For now, though, materialism is just the simplest, most logical account of the phenomena of mental processes. And that includes "free will." If we are really purely material beings, made up of flesh, bones, neurons, electricity, whatever, it stands to reason that all of those components obey the basic laws of cause and effect. Somewhere, deep within the recesses of the brain, there are memories and learned behaviors that are then combined, in the fraction of a moment, to form decisions. Of course, the way they are combined will be different for each person, thus giving rise to personalities and creativity; the materialistic view certainly does not deny the wondrous powers of the human mind to innovate, invent, and create new "combinations" that have never existed in the world before. We really are in the image of God. But not because we somehow stand outside the material universe. On the contrary (and I’ll return to this in the next part), because "we" stand inside it.

The mind is a phenomenon of the brain; consciousness an illusion of it. What we take to be the "self," a soul gazing out at the world but ultimately free from its influence, is but a mirage. Of course, we have "selves" in that my mind is not your mind, and my body is not your body. But our minds and bodies are wholly conditioned by other things: from genetics and how we were raised right down to how hungry we are right now. As I ponder the next words to write, 35 years of experience and thousands of years of genetic engineering are determining the choices that I make. "Free will" has nothing to do with it. Indeed, the whole delusion of the "I" is a temporary ripple on a pond of causes and conditions. The "I" is like a motion picture, an illusion of seamless movement caused by the rapid-fire succession of still images. Or, in Buddhist teacher Joseph Goldstein’s metaphor, this phenomenon of the "I" is like the Big Dipper: it’s there if you look at things a certain way, and not there if you look at them a different way. Of course, there’s no Big Dipper really; but equally "really," that is, from our ordinary, conventional way of looking at things, there is.

Now, as a lived, perceptual phenomenon – a phenomenon, not more – obviously free will exists, just like the Big Dipper does. This is the point of compatibilism: that free will exists to the same extent as other illusions do: it describes a phenomenon of our experience. If you think about it, what we really mean by "free will" is the absence of coercion. We don’t mean that your action is really free of conditions; we mean no one’s holding a gun to your head. Even though "your head" is, itself, entirely made up of conditions that are not "you."

This is why Rabbi Akiva’s statement in the Talmud that "everything is foreseen; yet free will is given" is not some Zen-like paradox. It’s describing just how things are. In actual reality, everything is "foreseen," if by "foreseen" we mean by an omniscient God who, unlike us but like Laplace’s famous demon, can actually know the billions of causes and conditions influencing each of us at every moment. In conventional reality, free will is given – a gift of illusion – and so is individual responsibility. And of course, there’s no way to know all of the individual causes and conditions which dictate even the most mundane of choices, and there is a faculty of the mind which is familiar to us as the "decider" which chooses among the different options – or which is so clouded, at times, that we might say one is not responsible for the choice. Faced with the opportunity to steal something, one rationally reviews the various factors in play, is non-rationally affected by various other factors, and a choice is ultimately made. It seems, indeed, as though "I" make the choice. Humans have adapted the ability to see themselves as autonomous agents, manipulating the world to their advantage, and it is a very useful ability – lose the sense of self, and crossing the street can be dangerous.

Or, in the Buddha’s words, "there is free action, there is retribution, but I see no agent that passes out from one set of momentary elements into another one, except those elements [themselves]."

So, if free will doesn’t really exist, but does exist for all intents and purposes, does any of this matter?

Sure it does.

2. Materialism is enlightenment

There are usually two consequentialist objections to the materialist refutation of free will: ethics and spirituality. These objections hold that without free will, we are amoral and mechanical. I will now argue the exact opposite: that the concept of a "real" free will, not its absence, is a detriment to ethical and spiritual progress.

a. It’ll be anarchy – not.

First, the supposed moral anarchy that results from the absence of free will simply does not occur. Legally, of course, all the penalties for conduct judged to be improper remain in place; until such time as we’re all so enlightened as to see that our selves do not ultimately exist, obviously conventional truth reigns in law, just as it does in our everyday lives, in which the self can often seem to matter more than anything else in the universe. And on the plane of personal ethics, moral culpability endures to the same extent as the notion of the self does. As the nondualist sage Nisargadatta said, "As long as you believe yourself to be in control, believe yourself to be responsible."

Ironically, our currently debased moral discourse is not entirely off the mark from this perspective. In the present American cultural moment, we have become accustomed to the "abuse excuse" – that childhood abuse "causes" a person to become a criminal, and thus they should, perhaps, get an easier ride. In fact, this is just an extreme and radically oversimplified version of all of our everyday urges and motivations. Your decision to steal or not to steal is also "caused" by your childhood – for most Zeek readers, by a moral education which taught us to despise stealing, or to appreciate its negative consequences for ourselves and others – as well as, of course, a myriad other causes and conditions. The claim of the "abuse excuse" is simply that the abuse in question is so strong as to override all the other (potentially good) motives in a person’s mind, even that of rational moral action; it’s one cause that defeats the ethical mind itself. A simplification, of course, but perhaps a useful one; after all, isn’t the point that the "ethical mind" is only a product of causes and conditions?

Legally, the question is different. Put generally, it is whether the mitigating circumstances are so extreme that they warrant a departure from our usual social norm, which is that no motivation justifies certain kinds of acts, such as murder. Generally we only do this when, again, we believe that  moral agency is itself absent, though it’s interesting in this regard to note the French exception for "crimes of passion," which can absolve even murderers of responsibility if their acts were committed in the heat of passion – e.g., when a man discovers his wife in bed with another man. Usually, however, while we all have urges to commit immoral acts, we still believe that people must repress them or face the consequences. Too bad that the gambling addict was stealing to feed his addiction, or the welfare mother to feed her kids; stealing is stealing.

moral agency is itself absent, though it’s interesting in this regard to note the French exception for "crimes of passion," which can absolve even murderers of responsibility if their acts were committed in the heat of passion – e.g., when a man discovers his wife in bed with another man. Usually, however, while we all have urges to commit immoral acts, we still believe that people must repress them or face the consequences. Too bad that the gambling addict was stealing to feed his addiction, or the welfare mother to feed her kids; stealing is stealing.

All this structure remains completely untouched with "free will" deleted from the equation. All that is happening is that our society is stating that some urges are to be respected more than others. If you are so unlucky as to possess an inadequate moral conscience, well, you will spend time in jail. And of course, we hope that the threat of doing so helps influence your decision. No metaphysics are needed, and the change in metaphysics does not lead to a degradation in morality or ethics.

On the contrary, it leads to a refinement in our understanding and a more rational framework for punishment. The criminal justice system, as legal philosophers observe, addresses several different, and often competing needs: public safety (deterrence falls within this category), retribution, rehabilitation, and compensation, to name a few. Outside the legal academy, our popular thinking confuses all of these. Sometimes, for example, we claim that our prison system is a "department of corrections," which would mean that those strategies which best work to rehabilitate a criminal should be selected. But then we hear that prisoners should "get what they deserve," which would mean that those strategies which best work to express our societal outrage at the crime should be selected.

Throughout, the conversation is, naturally, shot through with emotion – which is itself, for many theorists and non-theorists alike an integral part of the justice system. A founding myth of the Western justice system is Aeschylus’s Oresteia, in which the vengeful Furies are entombed right beneath Athens’ court system, both neutralizing them and, in a sense, institutionalizing them as well. Today, with "victim impact statements" and emotional jury presentations, it’s understood that emotions are intended to play some role in the justice system.

What would a justice system look like if it were animated by an understanding that the self has conventional truth only? A light example is probably the best place to start. When someone cuts me off in traffic, most of the time I get angry at them, cursing at them and judging them for being inconsiderate, rude, etc. On the rare occasions in which my more enlightened mind is present at the wheel, I understand that they were just doing as they must, just as my anger is doing what it must, and the whole clogged traffic artery is doing what it must as well. [The article Shakey: An Essay on Anger is devoted entirely to this point.] Again, I’m rarely so enlightened – but when I am, it’s obvious that I’ve got a more truthful, and wiser, perspective on the incident than when I’m ascribing blame. Does that mean that a traffic violator shouldn’t get a ticket? Of course not. It just means that the law should be applied in the way that best promotes public safety – not the way that does what I want, which is to teach that motherf–cker a lesson he won’t forget, goddamit.

Likewise, in more serious matters, imagine what it would look like if the criminal justice system were primarily oriented around preventing crime, as opposed to preventing crime and meeting our need for vengeance. To be clear, I’m not proposing any of these reforms actually be implemented today, because if our "need for vengeance" is left unmet, even greater harms might result. Rather, I’m suggesting that, if it were only possible to slowly, over time, work to lessen the intensity of those needs, we would end up with a more effective system of justice, not a less effective one. Our myths of free will aren’t helping; they’re hurting.

b. The machine without the ghost

b. The machine without the ghost

The second consequentialist argument for free will is that without it, we are like machines. No one wants to be dehumanized, and, so the argument goes, that’s just what all this materialist mechanizing does: it reduces us to biological instruments, with no spark of the Divine – or, in semi-secular terms, no human soul.

As longtime readers of this column know, I see this argument as theologically backward: the last gasp of the unenlightened mind, as I’ve titled this essay. If only we were able to release the need to see ourselves as separate from the rest of the cosmos! The autonomous soul isn’t the gateway to God; it’s the gateway to delusion. This is precisely the yetzer hara, the selfish, separating and, occasionally, evil inclination that sees the self as the center of the universe. Whereas, when I’m able to see, just a little bit, that my choices and feelings are the results not of my autonomous "free will" but of a vast Indra’s net of causes and conditions, the overwhelming majority of which I cannot know – not only a sense of perspective, but also a sense of peace, can arise.

It should be clear that I’m not approaching this subject from the detached perspective of the nondual theologian. This is how I feel. For example: I’ve led an interesting and unconventional life, with lots of different interests and stages and careers that at time feel incommensurate even to me. Sometimes I look at the choices I’ve made and feel a sense of gratitude and joy that I was able to make them. Other times, I feel great sadness, doubt, and confusion over not having a sense of mission, a feeling of "yes, this is the one thing I want to do." Sorting it all out keeps me busy, and my therapist employed; it’s an important part of my practice, and I’ve learned a lot. But when this sadness arises, the worst thing in the world for me to do is try to figure out the causes and rake myself over the coals yet again. The only path that has worked for me, other than distraction, is to pass through what I call the "gate of sadness" into a place of equanimity and clear seeing. This is the great koan of "shit happens:" that sometimes, sadness arises. It stays. It passes. It has nothing to do with "me" or my "free will," it’s just part of the causes and conditions. And no, it doesn’t feel good, and I can’t make it feel any different than it is – least of all with the pathetic self-delusions of conscious intention and the laws of attraction. It will be what it will be – ehyeh asher ehyeh– and my choice is simply what to do about it.

Sometimes, the conditions are present for me to allow it, appreciate it, and even enjoy it, in the same way one enjoys a sad song or a delicate flavor of food. Other times, different conditions predominate, and I can’t make it work – in which case there’s that much more to allow. "Stopping the war has no limits," as one of my teachers once said. There’s always more to let go. In either case, the delusion of free will doesn’t help. It doesn’t help me remember that I can make choices – I know that already, thanks. It doesn’t accurately describe my experience or my history. And it certainly doesn’t help me create a sense of intimacy with my God. It just makes me feel alone – and erroneously so.

Part of me hears that Jewish objection already brewing: "But if you just let go, aren’t you detaching from the world? What about tzedek, or tikkun olam?" Well, since it’s a Jewish objection, I’ll answer the question with another question: Which perspective is more likely to lead to pursuing justice, one centered on my self and my needs, or one which sees the arising of “my needs” as just one more strand within a web of causes and conditions – a web often given the name of God? I don’t know about you, but I’m a lot less selfish when I’m not self-centered; it seems like a tautology, really. Sure, too much equanimity can lead to a kind of ethical laziness; I accept, I accept, I accept, especially if I’m not paying the bill. But is that really equanimity? If we’re really serious about looking closely at the mind, then, it seems to me, a lot of what passes for equanimity and balance – not to mention "realism" – is actually selfishness in disguise. Detaching from the delusion of free will isn’t detaching from the world; it’s attaching oneself to it, and that makes ignoring its suffering in the name of domestic tranquility all the more difficult.

Yes, it’s clear that in the Jewish tradition, there are many examples of self-oriented people using their self-assertion to better the world, from Abraham arguing with God to Soviet refuseniks bravely asserting their individual rights. But there are just as many contemplatives who look clearly at themselves and the world, and find themselves compelled to act, from the Mother Teresas of the world to the volunteers in your neighborhood soup kitchen. Outside the Jewish world, this is the whole point of the Bodhisattva: that s/he becomes liberated from delusion first, and then turns back to the world. The Bodhisattva isn’t someone who stares liberation in the face and says, "no thanks, I’d rather help people." It’s someone who stares, is liberated, and then, from the place of non-self, the node of being known as the Bodhisattva functions as a kind of unobstructed compassion-machine. That’s the miracle of contemplative practice: that when you are fully honest, without the delusion – you’re compassionate without trying. It’s from there, not some kind of stiff-necked, argumentative, wrestling-with-God-because-really-I’m-sticking-up-for-my-ego rejection of nirvana for samsara.

As for me personally, I find that my tendency to evaluate things in terms of how good they are for Jay hinders, rather than helps, my advocacy. Whether I’m working on behalf of sexual minorities or environmental causes (the two areas where I do the most of my own social justice work), I find that the ego is not much help at all. It tends to make me want to make lots of money, instead of toil in the service of this supposedly noble ideal, which, my ego cynically reminds me, is really just me trying to feel better about myself. It causes me to balance the "good feelings" I get from changing people’s lives against renovating the bathroom in my house – completely omitting from the calculus the well-being of everyone else in the universe. You tell me: is the idea of self helping here, or hurting?

Nor is this erasure of the self an erasure of individuality. Letting go of the delusion of free will doesn’t mean that, beforehand, I’m a creative, idiosyncratic, lusting person and afterwards I’m a null. Everything still arises; it’s just seen for what It is, rather than what it isn’t. This is why some of the most enlightened teachers around today are still very much Brooklyn Jews, or British contrarians, or whatever their histories have shaped them into being. They may not even seem nice at first, and I’m sure that sadness and anger still arise. Only the phonies are always smiling – don’t believe a word they say.

"What about free will?" we are asked. Well, what about it: it’s an illusion of the well-functioning brain, a trick of the mind, and oftentimes the joke’s on you. Let go of it; you’ve got nothing to lose, and Nothing to gain. And there’s a big difference between nothing and Nothing, even though I can’t quite tell you what it is.

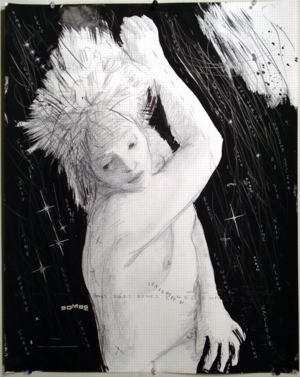

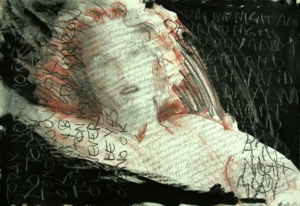

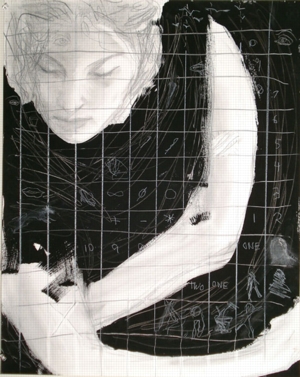

Images: Bombs bombs Bombs, and Indecision. Next Page: Deep Water and One Two by Audrey Anastasi.

Some really great articles on this site, regards for contribution.

An impressive share, I just now with all this onto a colleague who had been doing little analysis about this. And he in truth bought me breakfast due to the fact I discovered it for him.. smile. So i want to reword that: Thnx with the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending some time to talk about this, I feel strongly regarding this and love reading much more about this topic. If possible, as you grow expertise, do you mind updating your site with an increase of details? It truly is highly useful for me. Large thumb up because of this article!

Undeniably believe that which you said. Your favorite reason seemed to be on the web the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I definitely get annoyed while people think about worries that they plainly don’t know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the whole thing without having side effect , people could take a signal. Will probably be back to get more. Thanks