One Tuesday night [a few years back], I sat at a local cafe with a cappuccino and my just-purchased copy of Abraham Joshua Heschel's The Sabbath; all of my reading for pleasure seemed to be about Judaism at this point. I had already begun to understand why, on the seventh day, Jews traditionally refrain from lighting fires or using telephones or cooking food or spending money or doing many other things understood to be either technically "work" or outside the spirit of rest that governs the day

It seemed clear that abstaining from this stuff would create long stretches of silence and a freedom from distraction that could help a person access the most silent, hidden parts of the self. Heschel, however, explained that there was even more to it than that. He wrote,

To set apart one day a week for freedom, a day on which we would not use the instruments which have been so easily turned into weapons of destruction, a day for being with ourselves, a day of detachment from the vulgar, of independence from external obligations, a day on which we stop worshipping the idols of technical civilization, a day on which we use no money, a day of armistice in the economic struggle with our fellow men and the forces of nature-is there any institution that holds out a greater hope for man's progress than the Sabbath?[i]

The irony is that human progress depends on saying no to technology and economic engagement, at least for a while. Heschel framed Shabbat as a way of returning to too-oft-neglected ways of being human-a way to help us remember what we have in common with the woman who got up at 4 a.m. to clean the office.

The irony is that human progress depends on saying no to technology and economic engagement, at least for a while. Heschel framed Shabbat as a way of returning to too-oft-neglected ways of being human-a way to help us remember what we have in common with the woman who got up at 4 a.m. to clean the office.

I sipped my drink and I chewed on Heschel. The idea of being free from commercial transactions on Shabbat was attractive. I thought through the implications: If I didn't spend money, I couldn't get the eggplant sandwich I loved from the deli up the street. I wouldn't be able to ride the bus, since I never had a monthly pass. I needed Friday-night money to tip bartenders, pay cover charges, pick up the tab on a date, get into a movie. The list seemed to be endless. No eggplant sandwich?

This, I realized later, connected to all that stuff about desire I found in countless books on spirituality. Carol Lee Flinders wrote, "as long as I believe in sex as a source of lasting happiness-or power or food or even long weekends in the mountain or anything finite-then no matter how much I want the mysterious something else that mystics speak of, I can't walk toward it because my consciousness is divided."[ii]

In Buddhism, desire–uncritical servitude to our finite cravings–is considered the root of all suffering. The Ten Commandments tell us not to covet, not to desire greedily. Attempting to rein in my impulses, however, sounded terrible. The mere prospect of not being able to do what I wanted, exactly how and when I wanted to do so, was causing me no small amount of my own suffering. There seemed to be no winning.

Up until now, dabbling in Judaism hadn't demanded very much of me. I had time in my schedule for both Friday night services and clubbing, I could spare an hour's sleep every week or two for morning prayer and Torah class. Avoiding nonkosher food wasn't so hard-I hadn't eaten meat in years, and I wasn't really a fan of seafood anyway. But as I contemplated Shabbat, and what it might entail to deepen my practice, I began to realize that this spiritual discipline stuff was . . .well, more work than shooting energy out of the palms of my hands. If I wanted to move past the "random cool experiences" phase and into something more like Divine DSL, I had to actually do things to make that happen. I just wasn't sure that I was ready.

I wasn't alone in my hesitation to take this next step. A lot of people hit their limit of spiritual experimentation, I think, when it comes to facing down desires. The happy glow, the rushing ecstasies, and the feelings of being understood are all amazing. A class here or a retreat there is sweet, inspiring. Doing more than that is harder for a lot of us.

It's not like we have a lot of help and encouragement from the culture in which we live, either. As Caroline Knapp notes, "some twelve billion display ads, three million radio commercials, and 200,000 TV commercials flood the nation on a daily basis-most of us see and hear about 3,000 of them a day, all of them lapping at appetite, promising satisfaction, pulling and tugging and yipping at desire like a terrier at a woman's hemline."[iii]

It's not like we have a lot of help and encouragement from the culture in which we live, either. As Caroline Knapp notes, "some twelve billion display ads, three million radio commercials, and 200,000 TV commercials flood the nation on a daily basis-most of us see and hear about 3,000 of them a day, all of them lapping at appetite, promising satisfaction, pulling and tugging and yipping at desire like a terrier at a woman's hemline."[iii]

American culture today is the most consumer oriented in Western history, and the system depends upon our cravings. Buddhist environmentalist Stephanie Kaza suggests that "consumerism rests on the assumption that human desires are infinitely expandable; if there are an infinite number of ways to be dissatisfied, there are boundless opportunities to create products to meet those desires . . . How can [consumers] know what product will satisfy them when there are so many to try?"[iv]

With a little practice not running after our cravings, we begin to realize that they, and the feeling of urgency to satiate them, might not be as endless as we had thought. If, one day a week, all of our needs can be met with prayer, slow walks in the park, reading, Torah study, sitting in silence, and long communal meals that allow conversation to unfold, what might that tell us about the things that seemed so urgent on the other six? What might that tell us about our culture's stories regarding what we can and can't live without?

It's not that there isn't a place for work, music, travel, and, yes, spending money-the world needs us to be creators and doers just as it needs us to take breaks from all that relentless creating and doing. As Heschel framed it, "in regard to external gifts, to outward possessions, there is only one proper attitude-to have them and to be able to do without them."[v]

This was what Frederica Mathewes-Green meant when she said that we should enter one religious system fully and allow it to change us. Judaism was beginning to ask things of me, to intimate that it might be in my own best interests to take on practices that were neither convenient nor comfortable. Me? I wasn't so certain. It wasn't that I didn't want a deeper relationship to God and my religious practice, but that-like many of us who grapple with desire-I was terrified of the implications.

I had created a tenuous balance, one hand grasped tight around my Judaism, another around my social life. It felt like any sudden movements in one direction or the other would cause everything to fall. I was terrified to think I might become so religious that I'd lose much of what I had in common with the artists, activists, and slackers cum Unix administrators who made up my world. If I said no to what I wanted, would I get things that I needed, instead? That piece of me that was always itching for more-more God, more connection, deeper encounters that lasted longer-would it be satisfied? How much of my life, my friendships, would I lose by seeking this out? Would oh-so-holy Friday nights without spending money be boring? Lonely? Feel like some sort of a punishment? If everyone went out without me . . . then where would I be?

Saint Teresa of Avila writes of her own experience,

It is one of the most painful lives, I think, that one can imagine; for neither did I enjoy God nor did I find happiness in the world. When I was experiencing the enjoyments of the world, I felt sorrow when I recalled what I owed to God. When I was with God, my attachments to the world disturbed me. This is a war so troublesome that I don't know how I was able to suffer it even a month, much less for so many years.[vi]

I needed my friends. They had nourished and sustained me, helped bring me back to life after my mother's death, given me a sense of community the likes of which I had never experienced. I loved them-Jack and Lida and Michael and Ariel and Rebecca and

Cass and everybody else. If saying yes to God meant endangering these ties . . . well, I wasn't able to do that. And yet, it was clear that my relationship to God had become fundamental to the point of non-negotiability. Any attempts to run from it would just be denial doomed to failure. God was calling me, but I wasn't sure to where. God beckoned, but I couldn't face the price that I might have to pay to follow.

Cass and everybody else. If saying yes to God meant endangering these ties . . . well, I wasn't able to do that. And yet, it was clear that my relationship to God had become fundamental to the point of non-negotiability. Any attempts to run from it would just be denial doomed to failure. God was calling me, but I wasn't sure to where. God beckoned, but I couldn't face the price that I might have to pay to follow.

The Catholic priest Henri Nouwen wrote,

You have an idea of what the new country looks like. Still, you are very much at home, although not truly at peace, in the old country. You know the ways of the old country, its joys and pains, its happy and sad moments. You have spent most of your days there. Even though you know that you have not found there what your heart most desires, you remain quite attached to it . . . you know that what helped you and guided you in the old country no longer works, but what else do you have to go by? . . . Trust is so hard, because you have nothing to fall back on.[vii]

The feeling that I was living a double life began to wear. I still wasn't ready to throw away the full, flourishing existence that I had painstakingly built from scratch in a brand-new city, but inside the so-called flourishing life, I was increasingly lonely. That I felt like I couldn't talk about my desire for the sacred to become the organizing principle of my life meant that I had less and less to say.

My social life, like my freelance career, seemed to be far too much about the quest for the fresh, the exciting, the new, the next big thing. I, on the other hand, was yearning for the well tested, the eternal, the timeless. I was getting too much candy and not enough protein. Even costuming-which had become one of my favorite activities-began to lose its sparkle.

Though it had been delightful to reinvent myself over and over again, now I wanted to figure out who I was underneath all the artifice, underneath the makeup and the glitter and the thousand shifting guises. I still cherished the creativity demanded by the enterprise of getting dressed, but it began to be harder and harder to feel like I was "on" all the time. I started going out a little bit less, refusing invitations here and there. More often, though, I'd go out and simply not enjoy it.

All too frequently, it felt like there was something important missing from the conversation, something beyond romantic escapades, making rent, and the vicissitudes of pop culture. There just seemed to be a dearth of people with whom I could talk about this "something else," about not only my burgeoning religious life but all of the things that it might mean. My close friends' own spiritual lives allowed for some translation, but not enough. I needed people who were going through the same thing that I was, people who had also thought about keeping Shabbat or who were also afraid of their desire to become religious, and who might have some new ways for me to think about my private dilemmas. I needed those people, but I didn't see them anywhere in the life that I was already living.

Alex and I would later refer to this sense of longing as the search for the "party next door," for community and a life that felt cohesive, in which all of the social and religious aspects integrated seamlessly. At this point, however, I didn't know that there was a party happening elsewhere, or what kind of fun that could possibly be.

I wouldn't give up one life or the other. I'd refuse to tip the balance. And, in fact, I didn't stop spending money on Shabbat at this point; I just couldn't bring myself to take that step and face its possible implications. I'd just live with the discord, I told myself, keep letting the feeling in my solar plexus get trampled by the loud music at the bar. I'd notice keenly every time the check came at a restaurant, feel guilty and far from God as I reached into my purse for my share of the bill. This wouldn't be a long-term solution, and I knew it. The problem was, I didn't know what else there might be.

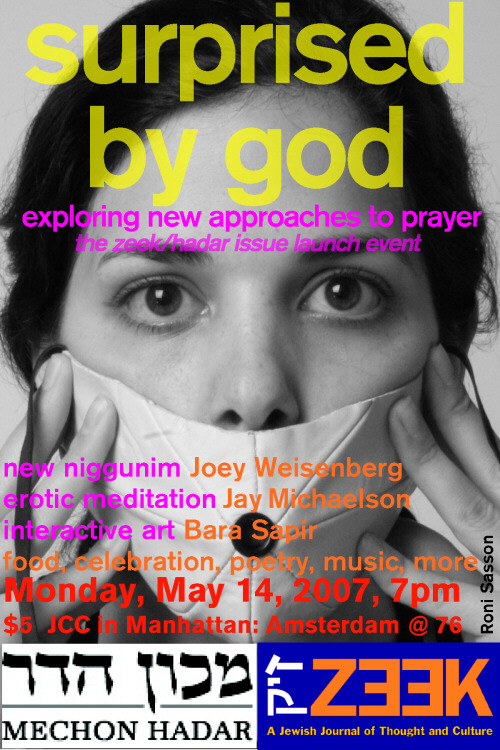

Reprinted from Surprised By God: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Religion by Danya Ruttenberg.Copyright © 2008 by Danya Ruttenberg. By permission of Beacon Press, www.beacon.org.

[i]Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1979), 28.

[ii] Carol Lee Flinders, At the Root of This Longing: Reconciling a Spiritual Hunger and a Feminist Thirst (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998), 71.

[iii] Knapp, Appetites, 15.

[iv] Stephanie Kaza, "Overcoming the Grip of Consumerism," Buddhist-Christian Studies 20 (2000): 23-42.

[v] Heschel, Sabbath, 28.

[vi] Flinders, Enduring Grace, 167.

[vii] Henri Nouwen, The Inner Voice of Love (New York: Bantam, 1999), 21.

I am glad to be a visitor of this thoroughgoing website ! , appreciate it for this rare information! .