‘What is this that God hath done unto us?’—Genesis 42:28

It is well known within the Marvel comics universe that Magneto is Jewish. While hinted at vaguely since his inception, Magneto “came out” of the shul in the 80’s, and his Jewry has been, if not forefront and center, then at least a constant undertone to his character ever since. Indeed, much of Magneto’s hatred and mistrust of humanity could—and has been—traced to the loss of his family as a child at the hands of the Third Reich. Numerous references in the comics—including a self-titled standalone run focused on Magneto’s bildungsroman in Hitler’s Germany—make sure that readers don’t forget this central aspect of the sometimes villain/sometimes anti-hero’s backstory.

Even the movie trilogies (both original and new) make a point of mentioning Magneto’s heritage (though not nearly well enough), perhaps due in part to the Jewishness of Bryan Singer, who has been involved in all six films, directing four of them. What seemingly appears as a victory of ethno-religious diversity, upon further examination, begs the question: how does Marvel, and pop culture at large, view the Jew?

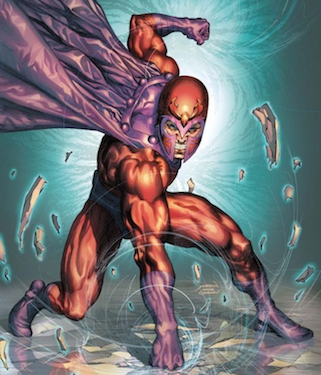

Due to their wild—if somewhat varied—success, the portrayal of Magneto by the movie franchise is the image most X-Men fans have of the “master of magnetism.” A sufferer of loss, Magneto is bent on assuring the safety and supremacy of mutantkind, led by his Brotherhood, no matter the cost, even at the expense of the lives of humans and mutants alike. His ethnocentric militarism, perhaps not dissimilar to the Israelites’ tribal conquest of the Promised Land, acts as a foil to his rival and (former) best friend Charles Xavier’s pacifism and Christ-like love and hope in humanity. This creates a dichotomous narrative wherein Christian coding exemplifies and equates compassion and pacifism with Christ, while Jews are maligned by (Christian) interpretations of God in the Old Testament as a vengeful, distant force. It excludes a whole realm of pathos from the Jewish psychology and enforces a negative, inherently anti-Semitic association between Jews and cruelty.

Evidence of this can be seen in Magneto’s storyline, across which a Moses metaphor, with a little stretching, can be neatly laid: a common man turned leader, promising to free mutants from the bondage and tyranny of humankind, who leads his followers through multiple bloody conflicts until they reach their Israel: the island sanctuary of Genosha. Though sometimes convinced to work alongside the X-Men for the greater good, Magneto remains—at least in the movies—opposed to and highly skeptical of Xavier’s philosophy, mainly due to his willingness to harm humans in his quest for liberation. This Jewish reading of Magneto, however, is a purely extrinsic viewpoint, which the movies do not at all portray or promote. Instead, Marvel movies see the Jew as one thing only: one who suffers.

The most striking reference to Magneto’s Jewishness, if due not to its gravitas then to its frequency, is the somewhat hackneyed “Holocaust Survivor” trope, which both movie trilogies embrace in nearly identical scenes. Magneto, a young boy, is torn from the arms of his mother at the gates of Auschwitz (beneath the rain, of course), and while screaming and reaching back for her, his burgeoning powers twist and warp the barbed-wire fence that now separates them. His survivorhood is referenced later, either through pointed language or shots of tattooed numbers on his forearm, to ensure the viewer does not forget that Magneto lived through the Holocaust.

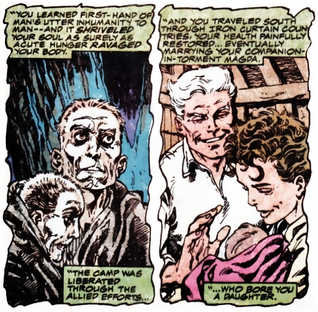

Any reference to Magneto’s Jewishness or Judaism (save for a few brief frames of a Chanukah flashback) are nonexistent. Though more attention has been paid to Magneto’s heritage within the comics, this coverage has been inconsistent, with scattered examples spread across decades and multiple creative teams. The references are there, but only for those willing to search.

Now, this distortion for one of Magneto’s primary aspects could be forgiven, seeing as X-Men is not a self-designated Jewish comic (despite the Jewishness of its two creators), except for the fact that this excessive hearkening to Magneto’s survival of the Shoah reinforces this idea that a Jew can be reduced to an overplayed image of an emaciated victim in striped pajamas. What it does is create a narrative of victimhood, through which, and only through which, a character’s Jewish identity is given voice. This is not to suggest that audiences need a flashback of Magneto studying Torah (though what a delight that would be), but what is required is nuance when it comes to the portrayal of Jews as complex, individual characters and not simply emotional clichés used to prop up or promote some tired understanding of an entire people as victims.

What it ultimately boils down to is (mis)representation. Dissenters are wont to point out that little if any mention is ever made of the Christian-hood of any of the other X-Men, and while this is true, by dint of our existence in a Christian centric society (within which the X-Men also exist) it is assumed that unless explicitly stated otherwise, all characters are Christian (or straight, etc.). Pointing out Magneto’s heritage matters because his is a background that so often goes unnoticed and unrepresented in mainstream media, but what matters more is how it’s represented. In both of his movie iterations, Nightcrawler’s Catholicism is subtly stated by brief scenes showing him praying, clutching a rosary, or making the sign of the cross. When confronted with overwhelming odds, his religion acts as succor for his soul, a shelter and support, all without being heavy handed.

The sole instance of Magneto speaking to God comes as an anguished crying out as he clutches the dead bodies of his recently murdered wife and child. Though this remains within the vein of traditional Judaism, where questioning God is not only common but oftentimes encouraged, the intent of the scene is most likely not to portray Magneto as a man succumbing to the pressures of the world while wondering aloud why the Almighty would burden him with these hardships. Rather, it only adds flare to the anguish of an already tortured man. Magneto does not overcome, he suffers.

Were this only an instance of poor or unimaginative character development, it would be bad enough, but the insidious truth of the matter is that Magneto is a snapshot of how pop media views the Jew. While there are certainly exceptions that prove the rule, for the most part, Jews are seen as two-dimensional caricatures, only interesting as victims to be saved or avenged. Think of the Jewish children in Au revoir, les enfants, whose impetus in the film is to be befriended by Catholics and yet still carted off to the concentration camps. Or the Bear Jew in Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds, who, by dint of his ability to actually fight back, must surely be a Golem, a construct of Jewish folklore. But Jews are more than victims and our stories more varied and complex than the narratives of suffering others wish to place upon us. Representation matters to be sure, but how we are represented matters just as much. A cast filled with stereotypes accomplishes little and harms more than it helps.

It’s time Marvel embraces the Jewish heritage of its characters and realizes that a Jew can do more than survive Auschwitz.

Alex Franco is a Georgia-born writer currently geeking out in Paris.

Read also: Hey, Marvel, Where Are Your Jews?

How Superman Stopped Being Jewish, And Why He’s Coming Back

Images: David Yardin and John Byrne for Marvel comics and via Wikimedia

328.962 Video. KATEGORİLER ARA CANLI CANLI. Üzgünüz bu video silinmiş!

Benzer Videolar. 17:1. Gerçek Anne Kamera Çıplak Almak.

Parti sırasında Arkadaşları 2 gerçek Kız Parmak ve.

I love to visit your web-blog, the themes are nice.::;:,